Ridley Scott, "Napoleon," and the Persistent Question of Historical Accuracy

The director's recent dismissal of historians critiquing his work indicates a missed opportunity for collaboration and a misunderstanding of the power of historical film.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

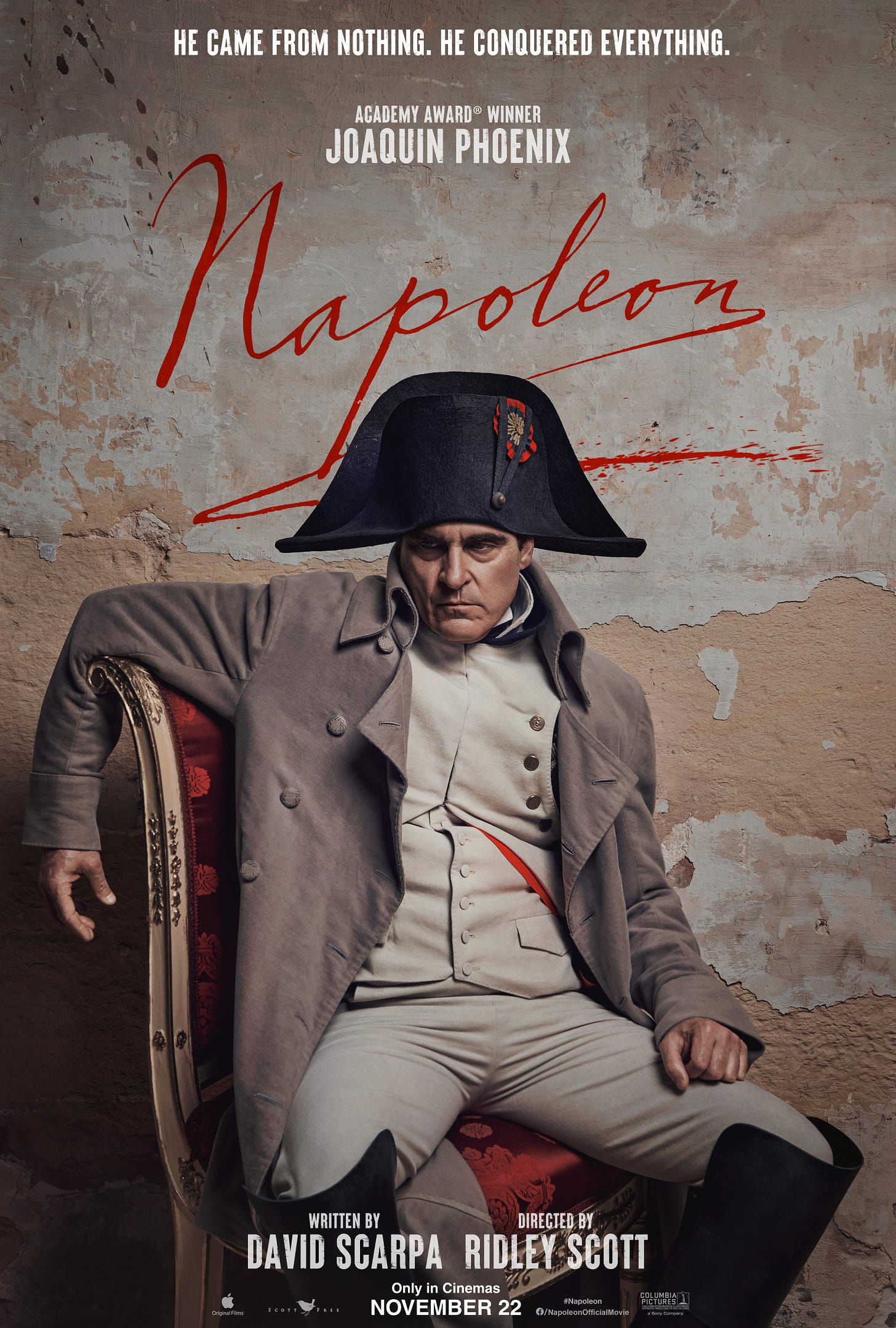

Well, it’s that time again: time for Sir Ridley Scott to release a major historical epic and then, when faced with some criticism for his approach, say something dismissive and more than a little mean-spirited. Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you are probably aware this month will see the release of his newest big-budget spectacular, Napoleon, starring Joaquin Phoenix as the infamous 18th/19th century French conqueror and emperor. If the trailer is anything to go by, this is going to be a true feast for the eyes, and there’s even some evidence that it might measure up to Gladiator, arguably the director’s magnum opus (at least as far as his historical films are concerned).

Indeed, there’s no question that Scott is one of the most talented historical filmmakers of his generation. Gladiator remains one of my all-time favorite epic films, and it feels as fresh and exciting in 2023 as it did when it first hit theaters in 2000. While some of his subsequent efforts haven’t quite hit as heavily or as powerfully as they should, I’m still a staunch defender of both Kingdom of Heaven and The Last Duel as remarkably thoughtful explorations of weighty historical issues. Say what you will about Scott, he knows how to deliver a historical epic that grapples with the past and how it shapes the present. There’s a reason, I think, that there’s a small library of articles and books written about Gladiator alone, primarily by classicists and historians who, like the rest of us, are entranced by Scott’s ability to make movie magic even as they are also aware of his shortcomings.

All of which brings us to the present, and his recent comments regarding the historical accuracy (or lack thereof) in his new big-budget spectacular, Napoleon. When asked what he thought about those who were pointing out some of the inaccuracies in his new film, he had this to say: “Get a life.” It was, on the one hand, utterly unsurprising that the director would be so dismissive of this line of criticism. He’s a British man in his 1980s, not exactly a demographic known for its sensitive approach to such matters. Moreover, the rather lackluster performance of his other recent projects–House of Gucci and The Last Duel–probably means that he’s even more prickly than usual.

At the same time, I found myself a bit taken aback by such a cavalier attitude toward historians, upon whose work Scott has relied in order to build his epic productions. Surely, given his own significant investment in bringing the past to life, he could do better in his response other than to offer a flippant dismissal equivalent to “fuck off?” If nothing else, surely he could have at least taken a few moments of his time to explain why it is that didn’t allow himself to get so hung up on the minutiae of accuracy that he lost sight of the creative energy of the project?

Now, to be clear, I’m not someone who gets hung up on questions of historical accuracy when it comes to screen depictions of the past. As a scholar and critic, I’m much more interested in the type of experience of the past that genres like the epic and the costume drama provide to viewers. Nevertheless, I do recognize that historians, at least, have a vested interest in making sure that the general public understands what really did and didn’t happen, what people wore and didn’t wear, and so on. This isn’t a sign that they have no life. It’s instead a sign that they take their duties as historians seriously. The best of them often realize that there are always some sacrifices that need to be made when it comes to creating fiction; they just want to make sure that such changes don’t come to be seen as the historical record rather than as inventions.

Of course, this isn’t the first time Scott has revealed himself to be something of a curmudgeon when it comes to any criticism of his films or his approach as someone who takes the past as his subject. When Exodus: Gods and Kings faced some (very justified) criticism for its whitewashing of ancient Egypt and its ancient inhabitants, he responded that “I can't mount a film of this budget...and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such...I'm just not going to get financed.” And, notably, he also said that his critics should get a life. Once again, one expects an old British man to say such things, but one would be forgiven for hoping that he would be a little more willing to engage with the deeper complexities brought to life by his own creations.

Nor is Scott alone in being one of those directors with a cavalier attitude toward the past they take so much pains to create. Mel Gibson’s Braveheart might be a stirring and sweeping piece of epic filmmaking, but it’s one of the most egregiously inaccurate films ever made. Gibson’s response: “"I'll admit where I may have distorted history a little bit," Gibson says. "That's OK. I'm in the business of cinema. I'm not an (expletive) historian." Fair enough but, as both Gibson and Scott must surely know, films like theirs exert a powerful hold on the public imagination and, as such, they have the power to distort understandings of the past if historians aren’t allowed and encouraged to challenge them.

That, I think, is the crux of the matter. Just as filmmakers have a responsibility to tell stories about the past in the best and most compelling way that they can, so historians have a responsibility to call them out for their mistakes. It’s in no one’s best interests to pretend as if historians don’t have something valuable to tell us about the past, particularly in an age in which a deliberate distortion of America’s history has become the norm among some segments of the American right. Rather than dismissing them, Scott and others would do well to bring them into the fold and engage them in a productive dialogue.

We would all benefit from such a conversation.