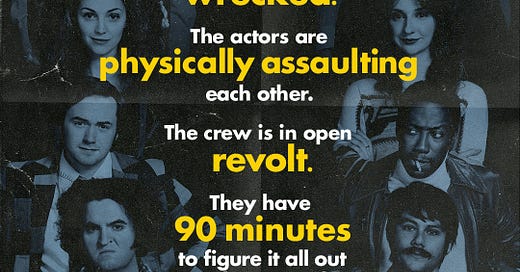

Film Review: "Saturday Night"

Jason Reitman's behind-the-scenes look at the first episode of what would become "Saturday Night Live" conjures more than a little of the chaotic magic that is live television.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Saturday Night Live has become one of those TV shows that can truly be said to be an American institution. Having first hit the air in 1975, it has since gone on to be a remarkable cultural bellwether and to have launched the careers of some of the most notable actors and actresses in comedy. And, while it can sometimes be wildly inconsistent–between seasons, within a season, and sometimes within an episode–it’s truly impossible to deny that it has had an enormous influence on both television and on American culture more generally.

If you were ever wondering about its origins, Jason Reitman’s Saturday Night (the show’s original title) aims to demystify it for you. Taking place almost in real-time, it documents Lorne Michaels’ efforts to get to get the premiere on the air, despite the fact that he is stymied at every turn: by the fact that there are too many acts to fit into an hour and a half of television, by faulty electric, by the resistance of the powers-that-be at NBC, and by the divas that he’s hired to perform during the show. Even Milton Berle (played here with scenery-stealing panache by the great J.K. Simmons) gets it on the act, taking the opportunity to hit on Chevy Chase’s girlfriend while emasculating the arrogant young actor by unzipping his pants and exposing his legendary genitalia.

Saturday Night has an unrelenting pace that can, at times, be somewhat exhausting, particularly since what’s going on in front of the camera is even busier and more frantic than the camera movement itself, which almost never stops. The film features a truly dazzling array of stars who would go on to become fixtures of the show, ranging from Billy Crystal (whose act is ultimately axed and who leaves in a huff) to such luminaries as Gilda Radner (Ella Hunt), Dan Aykroyd (Dylan O’Brien), and Chevy Chase (Cory Michael Smith). As a result, there are only a few that get to be sketched with anything but the broadest of strokes, such that Nicholas Podany’s portrayal of Crystal–like that of Matthew Rhys’ of George Carlin–end up being almost blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments.

While all this can be quite fatiguing at times, it’s also a very effective way of capturing the lightning in a bottle that was clearly a big part of the reason that the premiere ever got off the ground in the first place. Well, that and the fact that Lorne Michaels is himself a bit of a fast-talking spitfire, someone who excels at bullshitting, someone whose sheer sense of confidence and belief in his own vision is often enough to see him through. Gabriel LaBelle is a bit of inspired casting, for he not only bears a striking resemblance to the real Lorne but also embodies what must have been the producer’s indefatigable energy on that remarkable night in 1975. No matter what comes his way, whether a disgruntled and brittle NBC big-wig (played by Willem Defoe, who is almost everything these days) or a snarky Johnny Carson (heard via a phone call), he manages to make it through, though not without his own dark night of the soul moment.

Fortunately for him, he’s managed to gather together an extremely talented cast who in their own way are as determined to make sure that the show manages to go on. The one exception to this is John Belushi (Matt Wood), a man who might be supremely talented but is also notoriously prickly and difficult to work with, so much so that as the clock continues to tick it remains uncertain whether he’s even going to sign his contract. It also helps that he has an enormously talented and competent woman on his side, Rachel Sennott’s Rosie Shuster, his wife and collaborator and one of the key creative minds behind many of the sketches for which the show would become most famous. Unlike one of the other writers, including Michael O'Donoghue (Tommy Dewey), Shuster is a much calmer and more reassuring presence, one more able to soothe ruffled feathers and keep the ship going. It’s a more subdued performance from Sennott than we saw in last year’s Bottoms, but she once again demonstrates why she is one of the most charismatic of Hollywood’s younger generation of female stars.

There are some, however, who aren’t quite as enamored of Michaels’ vision for the show, and two characters in particular act as a sort of Greek chorus: Lamorne Morris’ Garrett Morris and Kim Matula’s Jane Curtin. Though their scenes are frustratingly short and limited, they nevertheless serve as important reminders that, for all of SNL’s undeniable power, it’s also fallen more than a little short when it comes to the female and BIPOC (not to mention queer) members of its cast. Moreover, I was a little disappointed that we didn’t get to spend more time with Gilda Radner who was, along with Belushi, Aykroyd, and Chase, one of those who really helped to make SNL into the extraordinary thing that it was in the beginning. She’s more of a perpetual presence rather than a fully-developed character in her own right.

Did I say that Saturday Night demystifies the origins of Saturday Night Live? Now that I think about it, there’s something quite magical about this film itself. Even though we in the audience know that somehow Michaels will manage to pull it off and that the show will indeed go on the air, the constant reminders of the encroachment of time lend the entire thing a frantic aura that gives it some stakes. And, given the extent to which the show would become such an enduring part of the TV landscape–before, arguably, succumbing to the very obsolescence that Berle and Caron seem to represent here–it’s helpful to look back on how it almost didn't happen at all.

In that sense, I don’t think that the film is “entertainingly pointless” as Ty Burr called it for The Washington Post, arguably one of the best examples of damning with faint praise that I’ve seen thus far this year, in film criticism or elsewhere. Given the status that SNL occupies in both good times and bad, surely there’s value to be had in taking a peek behind the curtain at what makes live television work? Moreover, isn’t there also value in turning our attention to But then again, maybe I’m just one of those people who really loves to see a movie that’s so in love with the magic of popular culture, that wants us to really bask in the fact that something as ersatz and dazzling as Saturday Night Live could ever have made it to the small screen at all, let alone endured through the decades.

In any case I loved it. Sometimes, a little bit of pointless entertainment is good enough on its own.