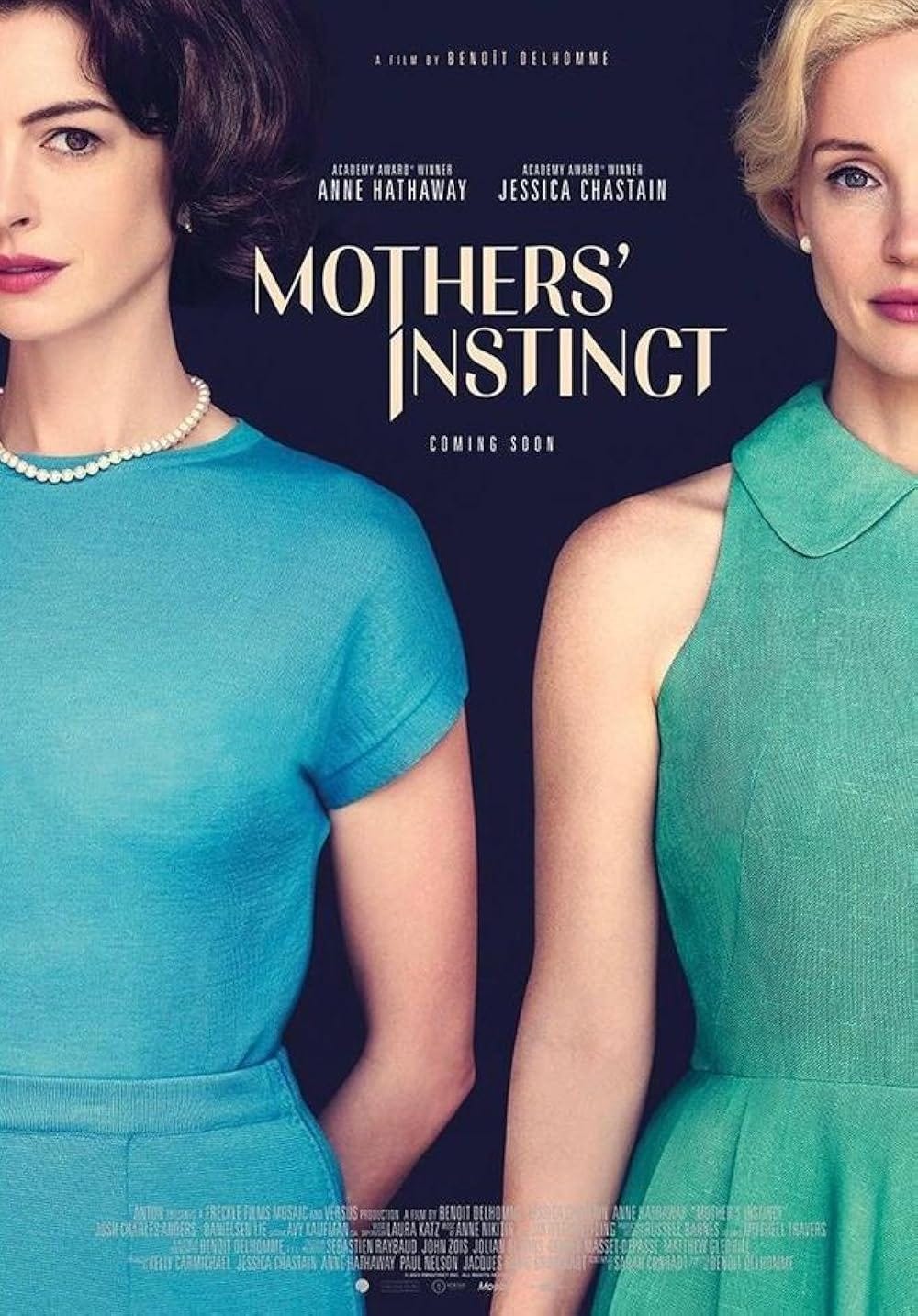

Film Review: "Mother's Instinct"

Part Hitchcock and part Sirk, this melodrama never quite hits its stride, but its two lead actresses deliver knockout performances that make it a compulsive and troubling watch.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Full spoilers for the film ahead.

Mother’s Instinct is one of those films that I’ve been wanting to see ever since I saw the trailer. After all, it has all of the ingredients to draw in a gay man like me, with its melodramatic storyline, Jessica Chastain and Anne Hathaway mothering all over the place, and a rich color palette that nicely and powerfully evokes the ethos of the 1960s. It’s part woman’s film and part horror, with just a dash of noir thrown in for spice. It doesn’t always hit its stride, but when it does it becomes an enjoyable and suspenseful film that highlights the raw, terrifying power of grief.

When the film begins Alice (Chastain) and Céline (Hathaway) are neighbors and friends. Their boys Max (Baylen D. Bielitz) and Theo (Eamon O'Connell) are likewise close. However, this seemingly idyllic life comes crashing down into tragedy and tears when Max tumbles from his death, leading Céline to suffer a breakdown. What follows is a twisty little melodrama as Alice becomes increasingly convinced that her erstwhile friend has become so unhinged with grief that she will stop at nothing to either destroy what Alice has or, if possible, seize it for herself. Little does she realize just how far she’s willing to go.

This is a film that lives and dies on its performances and its aesthetic. The story is, as this summary makes clear, in some ways quite ridiculous and meandering, and at a brisk 92 minutes Mother’s Instinct never really gets a chance to find its characters or its sense of identity. Thus, it falls to both Chastain and Hathaway to do a lot of the heavy lifting, and they more than deliver. Chastain digs deep into Alice’s psychology, ably capturing the various neuroses of a woman who lost her parents to a car accident and thus lives in a perpetual state of fear and anxiety. As it becomes increasingly clear that Céline may just have been driven mad by her grief over losing Max–a grief made all the more acute by the fact that she can have no further children–her anxiety skyrockets, and the film ably portrays what it’s like to feel as if your world is falling apart, even as everyone starts to think that you’re the one who’s lost it.

Hathaway, on the other hand, gives us something sultrier and thus something far more haunting. I’ve seen her referred to as vampish in the role, and there’s something to that. It’s clear from the first that she’s a more delicate creature than Alice, and she seems to always be laboring under the fear–justified, as it turns out–that something might happen to Max. It’s only when Céline becomes fully devoured by her grief, though, that Hathaway truly shines, and there’s a slyness to her performance that lets those of us in the audience know that there’s a vicious streak beneath her waifish demeanor. As her actions in the third act become ever more ruthless, it’s fun to see Hathaway give in to the colder part of her acting persona, one that we only periodically get to see (she channels a lot of this in Brokeback Mountain, so it’s great to see it here, too). The climax might strain credulity to the breaking point, but it’s chilling to watch Hathaway’s Céline methodically murder her husband and stage it as a suicide before chloroforming Alice and her husband and staging a gas leak, before taking custody of Theo for herself.

Visually Mother’s Instinct is a feast for the eyes. This isn’t particularly surprising, considering that director Benoît Delhomme has long worked as a cinematographer before taking up the director’s chair. He has a keen eye for color in particular, whether it’s the harshness of Max’s blood as a shattered Céline cradles his broken body or the shiny gleam of Alice’s blonde hair. The sumptuousness of both the color design and the costumes makes one wish for a more coherent story to go along with the Sirkian aesthetic, but alas, there’s just not enough time for Mother’s Instinct to really hit its stride, with some plot contrivances happening just to keep things moving. The suspense is effective enough in the middle part–largely thanks to Chastain’s performance and Anne Nikitin’s unsettling score–but I was left wanting more. Strangely enough, there’s just too much dead space in the film’s early parts in order to justify the melodramatic turns that it takes later on.

Beneath the melodrama, though, there’s also a bit of commentary about the plight of housewives in the mid-20th century. Though it isn’t elaborated on as much as I would have liked, there are several references early on to the fact that Alice would like to return to being a journalist, as doing so would give her life a sense of purpose and meaning that she lacks in her life. As far as Céline is concerned, there are hints of spousal abuse, and both women have spent at least some time in a mental hospital. For all that the midcentury period is still held up as some sort of idyllic age, Mother’s Instinct reveals the extent to which it was all a fiction, how the garden parties and immaculately-coiffed hair hid darker, more sinister secrets and a culture at war with itself.

While it never achieves the greatness toward which it aspires, I nevertheless found myself enjoying Mother’s Instinct more than some of the other critics out there. One can clearly see the influences of such directors as Alfred Hitchcock and Douglas Sirk and while, as others have pointed out, it never really attains anything close to what they were able to achieve at their best, it still does deserve some credit for setting itself such lofty goals. And, at the end of the day, I’m more than happy to sit and watch 90 plus minutes of two immensely talented actresses mothering their way across the screen. For all that they sometimes seem as if they are acting in two different movies, there’s pleasure to be had in watching two genuine stars act their hearts out.

Let’s just hope that Delhomme’s next feature is a bit more focused.