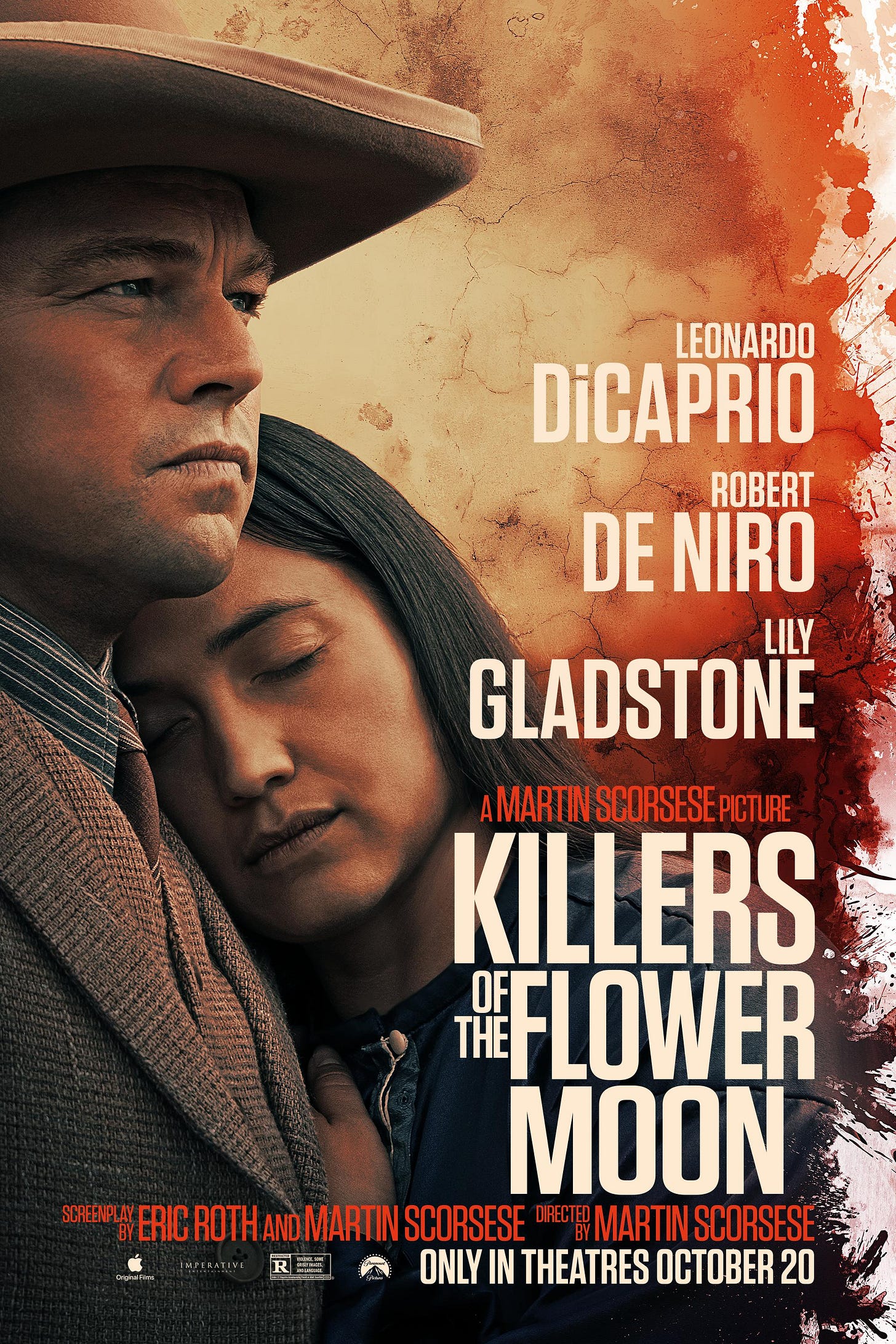

Film Review: "Killers of the Flower Moon" and the Banality of Evil

Martin Scorsese's newest film is a searing indictment of America's violent past and its continued exploitation of Indigenous people and their resources.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

I’ll be the first to admit that I had my reservations about watching Martin Scorsese’s new film Killers of the Flower Moon, based on the nonfiction book of the same name. I’m not immediately averse to any film that’s three and a half hours–I did write my dissertation on the biblical epic of the classic Hollywood era, after all–but even so this seemed like it was a bit much. When it finally came to Apple TV, however, I decided to give it a try, and I’m actually quite glad I did. In addition to being marvelously well-constructed (this is Martin Scorsese we’re talking about, after all), it’s also a brutal and haunting reminder of the violence perpetrated against Native Americans and our collective reluctance to admit it, let alone do anything to atone for it.

After the Osage discover oil on their land they rapidly become wealthy, though their access to said wealth is tightly controlled by the US government. Into this volatile arrangement comes Leonardo DiCaprio’s Ernest Burkhart, who reconnects with his uncle and brother and, after driving a cab, eventually courts wealthy Mollie, whom he eventually marries. However, he soon becomes embroiled in his nefarious uncle’s schemes to defraud and murder the wealthy Osage and procure their wealth, leading to his own fall and the near-death of Mollie.

DiCaprio is perfectly cast as Ernest, a young man who is for much of the film quite adrift and lost, which makes him the perfect instrument for his uncle’s subtle but brutal ambitions. This isn’t to say that Ernest isn’t evil, because of course he is. This is a man who is willing to kill others in cold blood, a man who is willing to both gaslight and poison his wife, all because he lacks the spine to confront his kin. Like so many of Leo’s other characters–particularly those who appear in a Scorsese film–Ernest is so enthralled by his father figure’s magnetism that he can’t summon the will to challenge him, at least not right up to the end (and even then there’s a moment where he almost refuses do so). The film never shies away from showing us the ugly side of his credulity, and there’s something both endearing and infuriating about DiCaprio’s performance. He’s ultimately a little boy that refuses to grow up and accept, acknowledge, and confront the evil he sees around him. There’s just enough of DiCaprio's youthful cherub to make it work.

Robert De Niro, meanwhile, is simply terrifying as William King Hale, Ernest’s Machiavellian uncle. For almost the entire film Hale keeps up his friendly, folksy demeanor and, because he’s played by De Niro, we almost believe it, simply because the man is so damn charismatic and charming. He only lets the mask slip a few times, and it’s here that De Niro’s star text proves particularly effective. Because we know De Niro from so many of his tough-guy roles, we can always sense the menace and danger lurking beneath Hale’s southern charm. He might not be the type of person to wield a weapon himself–except for one especially bizarre moment where he paddles Ernest inside of a Masonic Temple–but he is still exquisitely ruthless. Even more disturbing, perhaps, is his absolute belief in his own self-cultivated mythology. He repeatedly tells Ernest that the Osage, including Molly, don’t live long and that therefore the two of them have the obligation to make sure their oil rights pass to them. It’s horrifying to watch his magnetic hold on his nephews, and even more horrifying to see the brutal actions they carry out on his behalf.

For me, though, the real highlight of this film is, unsurprisingly, Lily Gladstone. She brings a quiet and dignified grace to the role of Mollie Burkhart, and she can say more with just a sly smile than many actors could say with an entire page of dialogue. There’s a knowingness–almost a world-weariness–to her performance, one which only grows more acute the longer the film goes on and the more members of her family are swept away by tragedy (i.e., her husband’s actions and those of his uncle). The comments when Mollie’s grief rips out of her in gasping wails is something that will haunt me for quite some time, and it is right to do so.

Now, I do think there is a great deal of legitimacy to the argument that this film, like so many others before it, tells a story of White exploitation and murder of Indigenous people. At the same time, I also think that, given White America’s almost pathological aversion to acknowledging historical wrongs, let alone doing anything to ameliorate the legacy of such wrongs, it does seem to me that Killers of the Flower Moon, with the power of its drama and its searing indictment of the injustice of it all, may move the needle at least a little in this regard. Moreover, the brilliance of Killers of the Flower Moon lies in its ability to show just how banal evil really is. Yes, both Ernest and Hale are monsters in their own way, but their appearances and mannerisms–Ernest’s boyish good looks and Hale’s aw-shucks demeanor–are potent reminders that appearances can be very deceiving. Sometimes those with the most corrupt souls look like our neighbors and our friends, much to our chagrin.

The film concludes with something of a darkly comedic moment, and the viewer watches as those involved in a radio drama relate what happened in the aftermath. Neither Ernest nor Hale really got what was coming to them, for though they did serve some time in prison, they were ultimately paroled. Mollie, meanwhile, went on to remarry, but her obituary made no mention of the fact that she was very nearly killed by her own husband, nor did it mention anything about the rest of the Osage murders. The (slightly bizarre) lightheartedness of this radio drama re-enactment is its own indictment of the way so many of us look at the history of America: as a performance, as something that can be safely gawked at and then dismissed. Scorsese is far too canny of a filmmaker to let us off that easily, and that last admission about Mollie hangs there, a reminder that history, and all of its traumas, are still unresolved.