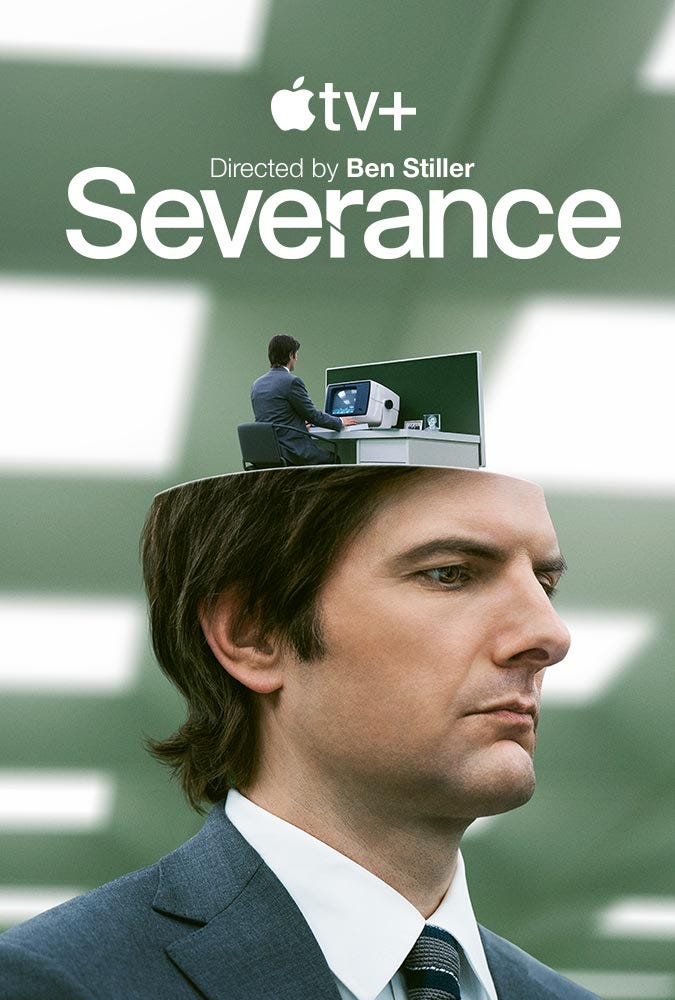

TV Review: "Severance" (Season 1)

The first season of the hit Apple TV+ series is a deeply disturbing and cunningly deceptive mix of black comedy, sci-fi, and dystopian satire. In short: it's brilliant.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Full spoilers for the series follow.

I know I’m a bit late to the party on this one, but I have to say that I absolutely loved the first season of Severance. Its remarkable blend of black comedy, satire, and science fiction hits all the right notes for me, and my partner and I were both hooked from the very first episode. By the time we get to the finale, we were left thinking something along the likes of: “what the fuck did we just watch and how we can get even more of it?” How fortunate for us that we checked in just in time for season two!

The central conceit behind Severance is one that is both deeply strange and yet all too familiar. A company called Lumon has perfected a method of “severing” its employees so that those on the severed floor have no memories of their lives outside. As if this weren’t enough, our central four characters–Mark Scout (Adam Scott), Dylan George (Zach Cherry), Irving Bailiff (John Turturro), and Helly Riggs (Britt Lower)--are part of a group known as Macrodata Refining Division, whose task is as meaningless as it is inscrutable. They are all overseen by the sinister-yet-cheerful Mr. Milchick (Tramell Tillman) and the even more sinister-yet-not-at-all cheerful Harmony Cobel (Patricia Arquette). As the series goes on, Scott’s Mark finds that not all is as it seems to be with Lumon and, along with the other members of his team, he starts to contemplate rebellion.

I don’t know what it is, but there’s just something about a woman of a certain age playing a formidable figure in power with a strange accent that does it for me. Patricia Arquette is certainly equal parts compelling and terrifying as Harmony Cobell, the manager of the severed floor. As it turns out, there’s far more to her than meets the eye, particularly since she is masquerading as Mark’s neighbor in the outside world. She vacillates, sometimes wildly, between icy calm and feverish intensity and, while she is herself just a cog in the Lumon machine, such is the intensity of her devotion to the company that she’s willing to look out for its interests even when it’s shown that she means little to it.

Adam Scott is, I think, the perfect person to portray Mark, the sort of everyman hero who slowly finds his assumptions about this world–both inside Lumon and outside of it, both his Outie and inner selves–turned upside down and inside out. Tramell Tillman is also well-cast, and he is superbly disturbing as Mr. Milchick, who in this first season is the seemingly chipper and optimistic supervisor. Underneath that handsome visage and dazzling smile, however, there’s a ruthless operator, someone who seems to be a true believer in the Lumon and severed cause and isn’t afraid to subject the men and women under his care to the horrors of discipline. The rest of the cast are also superb, though I find Britt Lower’s Helly a particular delight (even though she’s not all she seems).

Many shows have sought to capture the alienation that people feel in this despairing period of late capitalism, but I’m not sure that any show has done it with as much panache and such perfectly-paced dread. From the way that the higher-ups at Lumon try to distract the “Innies” from their bondage with little treats (and that infantilizing nickname) to to the vast and empty white hallways through which the characters so often wander, this is corporate life at its ugliest and most despairing. If you’ve ever worked in an office, it will all look very unsettlingly familiar, up to and including the extent to which all of the characters are engaged in a repetitive job–moving a series of numbers into little buckets on their screens–that seem to have no purpose that they can see. If this doesn’t describe late capitalism, then I don’t know what does.

The brilliance of Severance also lies in its ability to balance both its central mysteries and its own narrative propulsion. Some, I’m sure, will see the steady accumulation of mysteries a bit tedious to watch, but I found myself riveted by what I was watching. The series excels at binding us tightly to its narrative, and it all leads to a terrifying and powerful finale in which the innies finally manage to escape, for a brief moment, and thus to inhabit their Outie’s bodies and experience their lives. I’m not kidding when I say that I was on the edge of my seat, breathless with anticipation as to what was going to happen next.

On the one hand, we end the first season with just as many questions, if not more, than we had when we began. We still don’t know what it is that Lumon is working on; we don’t really know that much about severance as a process; and we know even less about the strange family at the heart of it all: the Eagans. What we do have, is some remarkable insight into the characters and their external lives, including Helly. Up until the end we’ve had no idea just who she is, so the revelation that she is herself an Eagan–who endured severance so she could prove to shareholders how harmless it is–hits like a bolt of lightning. Suddenly everything that we’ve seen of her Outie do and say makes sense, in particular her refusal to resign and allow her Innie to have the peace entailed in resignation. It’s a haunting moment, and it’s clear that nothing is ever going to be the same, just as nothing will be the same for Mark once he realizes that his wife, who he has long thought to be dead, is yet another slave in the bowels of Lumon.

The budding romance between Irving and Christopher Walken’s Burt Goodman is also a small island of sanity and warmth in a corporate atmosphere that is otherwise quite constricting and often terrifying. There’s a tenderness to their scenes together that reminds us that the Innies, contrary to what their Outies seem to think, have lives and emotions and loves of their own. Their story, perhaps more than any other, brings the stakes of the Innies’ lives and enslavement into sharp focus, particularly once Burt retires, meaning that his Innie essentially dies.

Severance is a remarkably timely show, given the extent to which our country–our businesses, our institutions, our very government–is slowly being eaten alive and rotted from within by the poisonous, avaricious logics of capitalism and corporate greed. I don’t think it’s going too far to say that all of us are, to one extent or another, in just the position as the central four, and it remains to be seen whether we will be able to claw back at least a little of our agency or whether we’re going to continue submitting to a system that sees us all as exploitable and disposable. There’s even something chillingly familiar about the ways that the severed employees of Lumon worship the members of the Eagan family, who are represented everywhere in works of “art.” This is the essence of Trump and Musk worship.

Suffice it to say that I loved this show. Apple continues to prove that it really is the place to be when it comes to sci-fi shows that push us to think about our world in new and sometimes terrifying ways. Its slate of science fiction may not be particularly optimistic–see also Silo, which is also about the question of control and the lengths to which people will go to reassert some measure of their own autonomy–but it’s still powerful. It also reminds us that we all have the potential to change our futures and that of the world we live in, if we’re brave enough to take the first step.