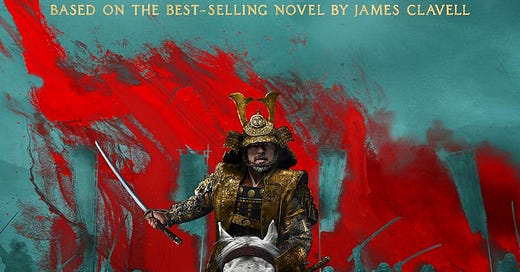

TV Review: In "Shōgun" the Past is a Foreign and Tragically Romantic Country

The hit FX series is a masterpiece of historical television, capturing the complicated nature of a key period in Japanese history.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Back in March I wrote about how much I was enjoying Shōgun and its ability to capture the complexities of historical change and development. Now that I’ve finished the show, I stand by my earlier claims, but I also have some new ones to add to the mix. In particular, I found myself quite enraptured by the way that the series uses the conventions of historical romance to both immerse western audiences in the strangeness of the past (and of a literal foreign country) and to allow for a deeper understanding of how one historical epoch ends and another begins.

It’s clear from the moment that Cosmo Jarvis’ John Blackthorne meets Anna Sawai’s Lady Toda Mariko that there is a spark between the two of them. Somehow the Anshin’s almost puppy-like demeanor manages to get beneath that placid surface and icy carapace she has erected around herself as a means of defending herself from her family’s lasting opprobrium. While he is almost bewilderingly simple as a character, Anna Sawai endows Mariko with a tragic grace, and her performance will, I think, come to be regarded as one of the finest in a historical television series.

Obviously, their romance serves in many ways as the emotional core of the show, the anchor that keeps viewers invested in the political drama unfolding around them. After all, these two people are living in an age of political tumult and unrest, in which an unsteady period of rule by a regency council is threatened by the rise of a powerful warlord Hiroyuki Sanada’s sly but stoic Yoshii Toranaga. Every step that Toranaga takes has an impact not just on the realm as a whole but on the beautiful but doomed romance between our two leads.

What’s particularly striking about Toranaga, however, is just how much of an antihero he is. At many points in the series he’s a right bastard, someone who is more than happy to sacrifice others on the altar of his own ambitions and his desire to become the most powerful man in Japan. This is a man, after all, who was willing to watch his own best friend and oldest adviser commit seppuku right in front of him so that he could convince those in power that he really was willing to submit himself to the authority of the other regents. This is also a man who sheds very few tears for the deaths of either his son or Mariko, the latter of whom he also sacrifices in his pursuit of power. This isn’t to say that he doesn’t have his own code of honor, but honor for Toranaga is inextricably bound up with what he believes is his rightful due. When it comes right down to it, he believes that it is his right and duty to be the shōgun, and it is this binding together of honor and ambition–as well as a political mind that is far, far shrewder than that of any of his enemies–that makes him such a compelling character. That, and Sanada’s truly magnetic performance. The man is somehow hot and menacing and deep, all at the same time.

If ambition and honor are bound up for Toranaga, it’s the latter which proves to be the true guiding light for Mariko. I don’t think I’m alone in thinking that Anna Sawai gives the performance of this series: she manages to capture so many layers of this character, and you can see a lifetime of pain and anguish in every move and gesture and facial expression. Ultimately, it is sacrifice that gives her life the meaning she has so long sought. When, later in the series, she throws herself in front of an explosion she is doing much more than sacrificing her life for the man to whom she has bound her fate and thereby forcing his enemies to betray their own honor; she is also attaining the peace and serenity that even her Catholic faith has so far denied her. It’s one of the most beautiful and romantic sequences in the entire show.

I know that the lack of a final battle in the finale left some viewers feeling a little disappointed or let down, but to me that is precisely the point of a series like Shōgun. This series has never been about big set-pieces like those in Game of Thrones (to which this series has been exhaustingly compared). Instead, it has been about the tiny human dramas that are always part and parcel of the great moments of historical change. It’s about love and tragedy, and it’s about political machinations and codes of honor. The lack of climactic battle scenes forces us as viewers to pay much more attention to the humanity at the heart of it all, and for that I, as a lifelong fan of historical miniseries, am grateful.

However, I think the thing I appreciate the most about Shogun was the extent to which it made me feel as if I was truly bearing witness to the strangeness of the past. Western audiences like myself are thrown into a world and a time period that is unfamiliar to us and, like our main character, we are sometimes quite flummoxed when it comes to the system of honor that governs so much of the Japanese characters’ behavior. Who, for example, wasn’t more than a little horrified when, near the beginning, the samurai Tadayoshi ends up committing seppuku after shaming Toranaga, taking not only his own life but that of his son? Within the context of the series and the world it depicts, however, this is all perfectly natural and acceptable, even though we are often as perplexed as Blackthorne.

Whereas Blackthorne’s inability to fully grasp the niceties and nuances of Japanese culture are at least as much due to the language barrier as they are to culture shock, we at least have the advantage of being able to understand what all of the characters are saying. Even so, this series doesn’t attempt to make its Japanese characters or their actions palatable to western eyes, nor does it file away the sharp and jagged edges of the past. This is a complicated world, one that is as refined and beautiful as it is brutal and bloody, and Shōgun gives it to us in all of its complexity.

There is, then, something remarkably evocative about the last frame of the series, which sees Blackthorne reunited with his destroyed ship and Toranaga poised to take over the world he has created, with the last shot showing him gazing into the distance. He is in many ways a colossus bestriding the world he will bring into being, the future spread out before him in ways that only he could have envisioned. A very poetic and romantic end, indeed.