TV Review: "Fellow Travelers" and the Contradictions of Queerness

The new Showtime series is a beautiful, sexy, and haunting look at the fraught nature of queer life and history in the 20th century.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Spoilers for the entirety of the show contained herein.

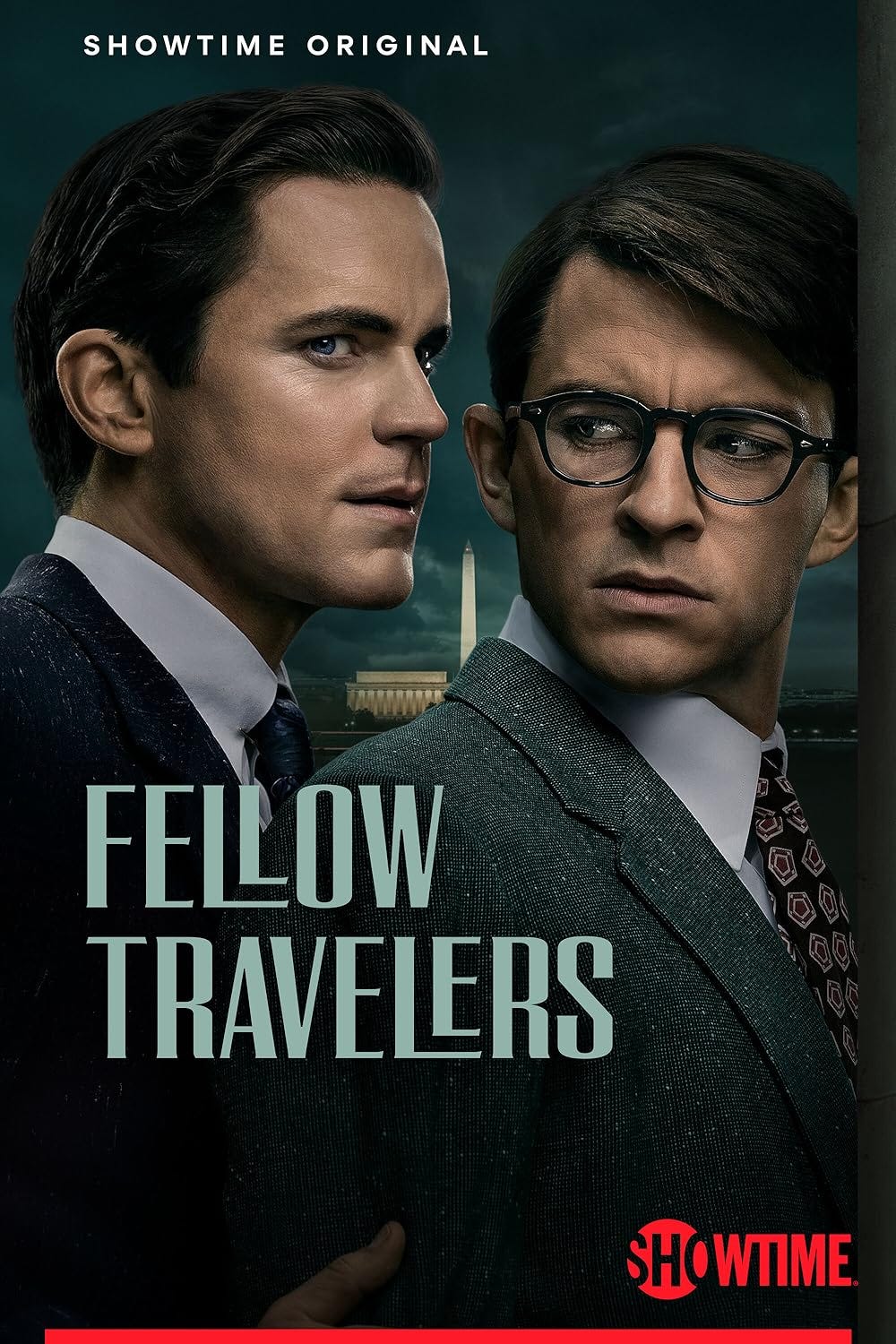

Like every other gay man of my acquaintance, I’d been eagerly awaiting the release of Showtime’s The Fellow Travelers ever since we got our first glimpses of the miniseries based on the novel of the same name by Thomas Mallon. I’ve been a fan of both Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey for years now, and I think it is safe to say that their roles in this series will come to define their careers. They both deliver performances that are at once effortlessly charismatic, deeply soulful, and utterly heartbreaking, their undeniable male beauty making their story all the more achingly poignant.

The series begins in the 1980s, and Bomer’s Hawkins Fuller is informed by Jelani Alladin’s Marcus Hooks that Tim Laughlin (Bailey), their mutual acquaintance, is dying of AIDS and is getting his affairs in order. Hawkins (who goes by Hawk for short) leaves his long-suffering wife, Lucy (an under-appreciated Allison Williams), and flies to San Francisco to make peace with Tim. As the series unfolds in both the past and the past–spanning three decades in the process–we see their relationship in all of its fraught and difficult intensity, even as the US changes around them.

From the moment we meet Hawk, we know that he’s a man’s man. Part of this stems from Bomer’s chiseled beauty, but an equal part emerges from his almost animalistic sexuality. He’s the kind of man who fucks who he wants to fuck and then moves on. For Hawk this is both a personal and a political necessity since, as an employee of the State Department and the intimate of a sitting Senator, he has to guard his sexual escapades zealously, particularly once the Lavender Scare begins to heat up in earnest. Despite his rigid investment in his masculinity, there are glimpses of tenderness, particularly once he meets the boyish Tim, whom he nicknames Skippy.

Tim, like Hawk, embodies many of the contradictions of his generation. When the series begins, he is a diehard acolyte of Senator McCarthy, and while he quails at some of his brutish tactics–and those of his deputy, Roy Cohn–he nevertheless believes in the fundamental rightness of their His greatest conflict, however, is within himself, as he struggles to reconcile his devout Catholic faith with his love for Hawk. Tim ultimately reconciles the various parts of his life to a degree Hawk doesn’t (at least not until near the end of the series), ultimately becoming a social worker in California and a passionate activist.

It’s clear from the moment that they meet theirs is the love for the ages. They are both the inverse image of the other, but this is precisely what makes them so perfect. Theirs is a desire, and a love, born out of turbulence, terror, and the closet, it is for this reason that the sex scenes that occur with regularity are so necessary. It is only when Hawk and Tim are entirely enmeshed, their bodies intertwined in the throes of lust and yearning, that they can finally have the happiness and contentment that eludes them in the world outside the bedroom.

There’s an fiercely intense, almost primal energy to these moments, and I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that they are some of the most sexually explicit scenes I have ever seen on either the big or the small screen. The beauty of them, however, is that they feel so intrinsic to these characters, their struggles, and their identities. If nothing else, their power is a testament to the enduring power and importance of such scenes in queer cinema in particular. Sex is so essential to so many gay men and their sense of themselves–to say nothing of their bonds with one another–that it’s impossible to imagine a series like Fellow Travelers without it. This is sex as both an expression of character and a reflection of said character, and the show, and viewers, would be much poorer without it.

But because of the deeply riven era in which they live, Hawk and Tim struggle time and again to really find happiness with one another. Like Jack and Ennis of Brokeback Mountain, they come together every few years, only for their differences to tear them apart. Hawk marries Lucy and has a family, but they are never truly happy or content with each other, precisely because Tim is the presence neither of them dare name. Though they are ultimately brought together by the tragic death of their son, they are driven apart once again by Tim’s final illness.

Ultimately, both Hawk and Tim find their own measure of peace, both with one another and with themselves. They finally share the rapprochement they have both longed for, each of them admitting–either explicitly or implicitly–that they love each other, even though by this point they know that their love can never be partners in a way each of them would like. Their contradictions, and Tim’s impending mortality and desire to be a fierce advocate for those dying from AIDS, ultimately push them apart for the last time. There is, though, a peace to this final parting, as each finds comfort in their love for the other. It is, I think, the perfect queer contradiction.

It’s thus fitting that the series ends with Hawk making his way across the AIDS Quilt, seeking out the panel devoted to Tim. In the series’ final moments, he finally admits to his daughter that Tim wasn’t just his friend; he was the man he loved. Even though it passes by in a flash, there’s something truly devastating about Hawk’s admission of his love for Tim, It’s not just that this is the first time that we have heard him say that he loved the other man–he never really told him during his life, though he did show him in every way that he knew how–it’s also that this is the first time he has really been honest with his family about his true identity as a gay man. For so much of the series the closet has been the structuring reality of Hawk’s life, shaping every decision, distorting every love, corrupting every bond. In addition to exposing and forcing a confrontation with the contradictions of queer history, Fellow Travelers also succeeds in showing the pernicious power of the closet on so many 20th century queer folks.

This plays out in ways both large and small. Lucy’s brother is sent to an asylum to be “cured” of his sexuality, an event that leads his father to commit suicide. Black journalist Marcus, meanwhile is, like Hawk, caught between various contradictory parts of his identity: as an African American trying to make it in the White world of journalism; as a gay man trying to forge a life with the much more openly queer Frankie (a magnificent Noah J. Ricketts); and as someone fiercely protective of his own masculinity. The romance between Marcus and Frankie is just as fraught as that between Tim and Hawk, though it (presumably) ends more happily.

Fellow Travelers is the type of series that reaches inside you and rips your heart to pieces, all before putting it right back in and expecting you to go on with your life. Like Hawk and Tim, we all have to learn to make our own form of peace with our internal and external contradictions, with all of the ways that being queer sets us apart in the world. It’s a lesson both timely and timeless.

I think Hawk stayed away to honor Tim’s wishes, but kept abreast of Tim’s health status with Marcus.

I need to know, does Hawk leave before Tims dies and that's their final goodbye? In the book Mary delivers the news but I don't think that would carry through to the show. Do they separate and then Tim dies later or does Hawk know Tims going to die and leaves after they finally realize what they both mean to each other? Loving the series but it's keeping me up at night not knowing