The Timely Wisdom of "The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse"

The Oscar winner contains a beautiful bit of soft wisdom for those who allow themselves to see it.

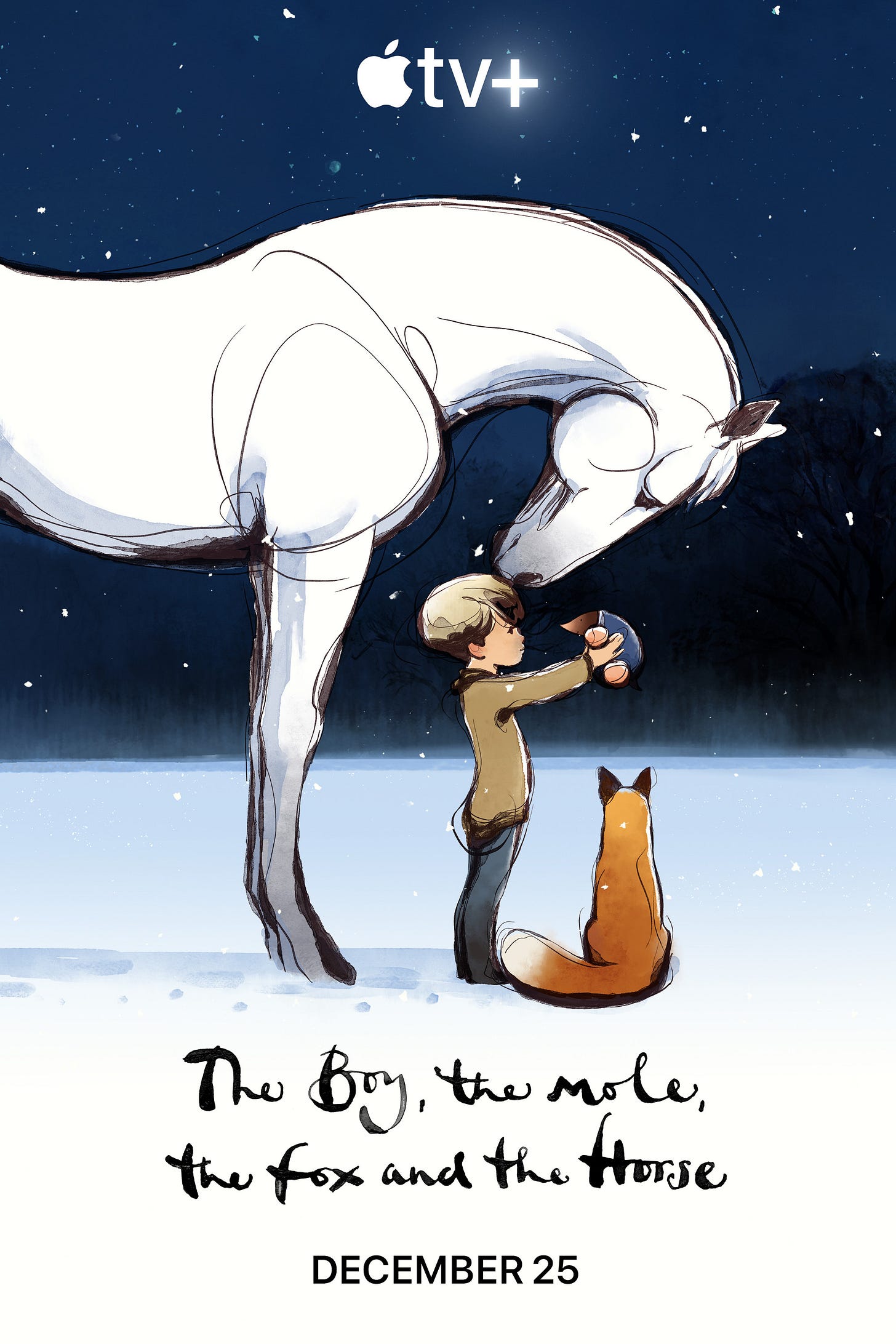

There is, I think, something uniquely pleasurable about a simple story told well. That is certainly the case with The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse, which recently won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film at this year’s Oscars. Based on the children’s book of the same name by Charlie Mackesy, it follows a little boy lost in the woods who befriends the creatures of the title, who lovingly teach him a variety of lessons.

It’s hard to put into words just why I, personally, found this film so deeply and profoundly affecting (I sobbed most of the way through it). Perhaps it’s because, like Paddington and Paddington 2, there is an elegant simplicity to the story which, like so many of the best children’s stories, is about finding one’s way out of seemingly impossible situations and about learning valuable lessons about self-acceptance, love, and discovering a home in the most unlikely of places. To some, these messages might seem banal or so obvious as to be laughable. Do we really need a short animated film to remind us of the power of loving yourself and embracing family wherever you find it?

I would argue that we do.

As Emily Bernard of Collider argues, we live in an age of distraction and, just as importantly, we are all so obsessed with projecting the right image of ourselves. We constantly drive ourselves further, desperately trying to prove our value to others and to ourselves. What’s more, we are also living in a troubled and divisive time, one in which many people, particularly in the LGBTQ+ community, regularly find themselves on the receiving end of rejection at all levels of society.

Thus, there is an undeniable magic to this film, both in its substance and in its execution. The animation looks as if it has been lifted straight from Mackesy’s original novel, but graced with the fluidity of movement and the unique magic that is the province of film animation. As a result, we feel as if we have once again been immersed in the world of childhood, with all of its perils and its promise. Each of the characters is rendered in such a way that they seem like real creatures, even if their exaggerated proportions suggest the fantastical (this is particularly true of Mole).

And, in the tradition of so many other fairy tales, each has something valuable to teach the Boy, themselves, and the viewer.

For the Mole, life is very simple. Embrace the joys and the pleasures of the moment (particularly cake), while for the Fox it is the importance of overcoming one’s traumatic past to accept love when it is freely given. And, for the Horse, it is about being true to oneself, and he teaches the boy the value of tears, of seeing them as a sign of strength, not weakness.

Yet even within this relatively simple rendering there are deeper currents. For all of his transparency, the Mole still finds it difficult to express his feelings as completely as he’d like, which is why he prefers to say “I’m glad we’re all here” as opposed to the more fulsome and effusive “I love you all.” The Fox, clearly, has endured rejection in the past, and he has responded with anger (ably conveyed by Idris Elba’s bristling vocals). Even the Horse, arguably the wisest and more grounded of them all, hides a secret: he has wings, but he prefers not to fly, because he doesn’t want to make the other horses jealous. The Boy’s presence affects all of them just as much as they impact him, changing all of their lives for the better.

I’ll admit that, as the film reached its conclusion, I was deeply afraid that the Boy would abandon his newfound friends in favor of the world of civilization, that he would find a home among others of his own kind rather than with the companions he has made along his journey. However, presented with the chance to find home in a human village or staying with his friends, he opts for the latter and, as the film reaches its conclusion, the Boy sits with his new family, gazing up at the vast spread of the night sky. It’s an achingly beautiful moment, particularly for those who have, like the Boy, sought comfort and solace and beauty in a found family.

The power of animation lies, at least in part, in its ability to transport us out of the realm of the real and the mundane and the everyday, and it’s for this reason that I’ve always thought that it was the entertainment form which most fully demonstrates Richard Dyer’s notion of utopia. This may help to explain why it has always struggled to gain the respect of far too many “adults,” who continue to insist that there is nothing (or at least very little) worth taking seriously in animation (thank goodness for Guillermo del Toro, who used his Oscar speech to once again come to its defense). Furthermore, it’s hard to escape the cynicism that seems to have permeated every aspect of our lives and our society. Most everyone seems to go out of their way to find fault and to criticize, to ostracize and to cast out, and though the worst of the pandemic seems to be in the past (we can but hope), the scars it has left behind are deep and, it seems, unlikely to be healed anytime soon, if ever.

If you’ve read this newsletter for any length of time, however, you’ll know that I go out of my way to find things in the world that bring me joy, that remind me of the beauty and the wonder of the world. The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse is one of those things, and my only gripe is that its exposure is somewhat limited by the fact that is available only on Apple TV (though I’m sure the fact that it won the Oscar helped to boost its visibility). The wisdom of the film lies in its ability to remind us to slow down, to look within, and to love both others and ourselves. It’s a simple but powerful message, and it’s one we would all do well to heed. Sometimes, it really is better to embrace the clear vision of a child.