The Prick of Longing in "The Hours"

The poignant film demonstrates the power, and the peril, of longing.

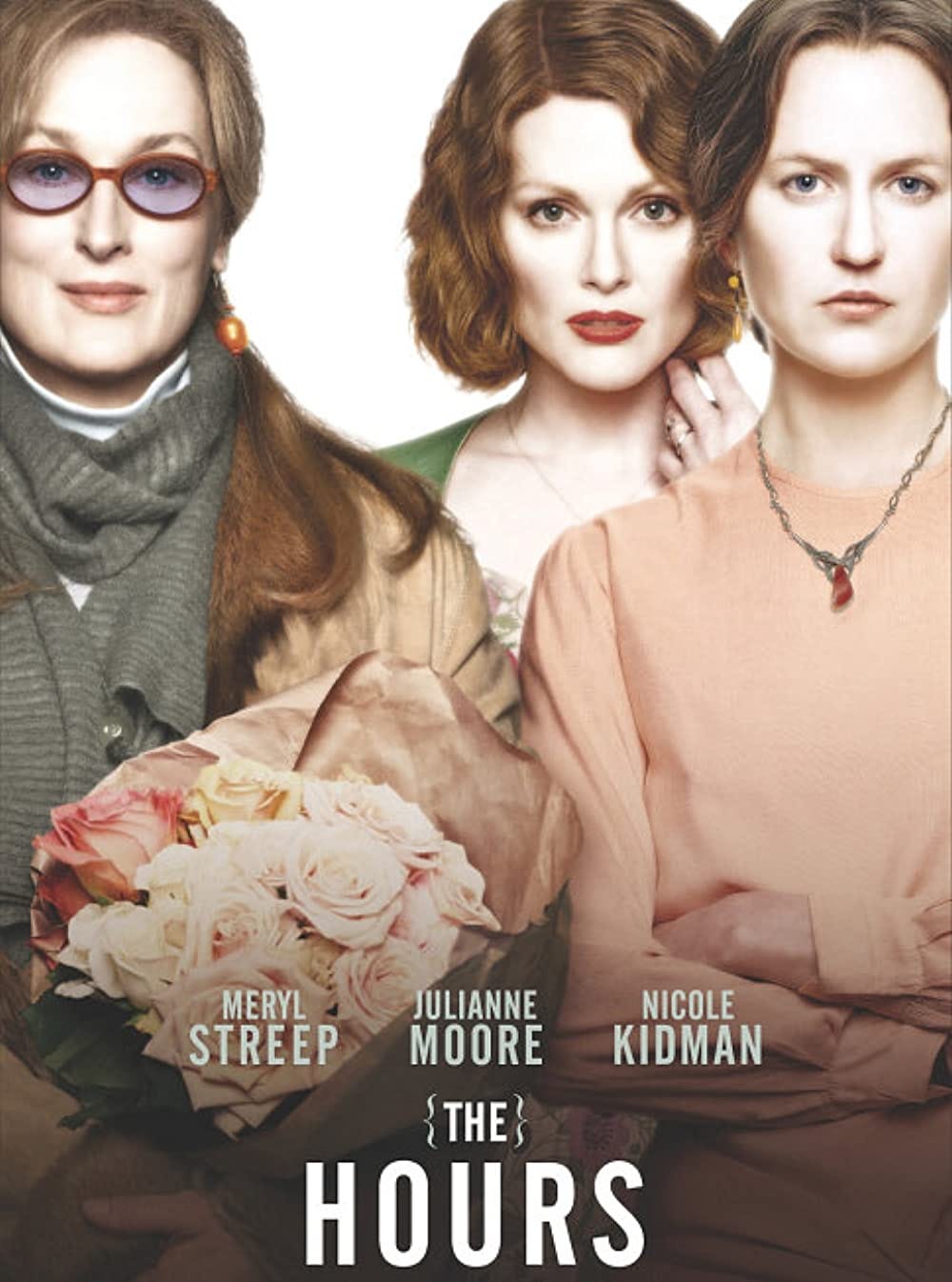

The Hours is one of those films that’s been on my watch-list since forever but, for some reason or another, I’ve managed to not watch it. This, despite the fact that it stars three of the fine actresses of their generation–Nicole Kidman, Meryl Streep, and Julianne Moore–and despite the fact that it’s very much a queer story. Well, thankfully, I finally decided to rectify that oversight and watched it. And, let me say, it is one of the most moving and haunting film experiences I’ve ever had.

If you’re unfamiliar with the film (or the book on which it’s based, written by Michael Cunningham), it follows three different women in different times: Virginia Woolf (Nicole Kidman) in the 1920s, Laura Brown (Julianne Moore) in the 1950s, and Clarrisa Vaughan (Meryl Streep) in the early 2000s. All three women struggle against the imprisonment they feel, whether it’s the mental illness of Woolf, the cult of domesticity for Brown, or the hopeless longing for a man she can never have that haunts Vaughan. Indeed, more than anything else, The Hours is a rumination about the power of longing to imprison us in a world of our own making, one from which death all too often is the only escape.

This is certainly the case for Virginia Woolf, whose narration and novel, Mrs. Dalloway, frame the story and informs the film’s entire sensibility. In Kidman’s extraordinary hands, Woolf emerges as a woman truly haunted by the life she knows she can never have. Taken to the country by her husband, who believes doing so will help her achieve some measure of emotional and mental peace, she finds herself withering away far from the hustle and bustle of London, the one space that seems capable of feeding her need to be creative and to express herself. She seems to know on some level that her own extinction is inevitable, and so she finally convinces him to let her return to the one place she feels most fully herself, most fully alive.

Longing is also a key motivator for Moore’s Laura. Like Woolf, she finds herself exiled to the suburbs, where she struggles to find the happiness she knows should be her right as a postwar housewife. However, everything about her life feels discordant, both to her and to us. Her efforts to bake a cake for her husband fails, her son’s voice always seems to ring discordantly, and he clings to her as if he senses, in that unsettling way that children so often have, that something is not right. And so it proves to be, for she has decided on suicide as the only way out of the prison of postwar conformity. Though she ultimately decides not to take her own life, she does leave her family behind after the birth of her second child, forging a new life as a librarian in Toronto, far away from everything that came before.

Of the three women, Streep’s Clarissa is the one whose story most resonated with me. When the film begins she is, like Mrs. Dalloway, planning a party as a means of distracting herself from the dissatisfactions of her own life. In particular, she harbors deep-rooted feelings for Richard, her dear friend, former lover, and writer, who is dying of AIDS. Though she doesn’t say so explicitly, it’s very clear from everything about her–from the stilted relationship she has with her long-term partner Sally (an unfortunately underused Allison Janney) to the way she can never quite bring herself to be comfortable around Richard–that he is the one great love of her life, the one person she can never fully let go of. As a Pisces and someone who loves nothing more than the bittersweet melancholia of unrequited love, Clarissa’s story seemed to prick me, leaving an emotional bruise I’m still struggling to heal from (yes, I’m alluding to Barthes, in case you’re wondering). How not, when her own plight is one I face myself, as I recall all of the loves I’ve had and might have had, now vanished forever into the vault of the past? How do you move on from the feelings you’ve had, when the person is still there and when you genuinely care about them and their well-being? How do deal with the perpetual reminder of what you can never have?

As much as Clarissa’s story echoes my own feelings for the many loves I’ve had to leave behind, it’s Woolf’s last words that have stuck with me. In the film’s final scene, she walks slowly into the river, returning us to the same moment with which it opened. With the water slowly rising around her, her voiceover intones from the suicide she left for her husband Leonard: “Dear Leonard,” she intones, “To look life in the face, always, to look life in the face and to know it for what it is. At last to know it, to love it for what it is, and then, to put it away. Leonard, always the years between us, always the years. Always the love. Always the hours.”

There’s so much about this quote that pricks us. There is the context, Woolf’s haunting suicide, and there is, of coures, Kidman’s delivery, so crisp and yet so deeply evocative (she remains a master of delivering haunting dialogue). More than anything else, perhaps, it’s a reminder of the temporal finitude of our own lives, and how it is only in hindsight that we come to realize how important those hours were to us, even as they slip by us, as relentless and as changing as the river which slowly swallows up Woolf, sending her into a peaceful oblivion. Woolf’s words are later echoed by Clarissa, who says to her daughter, “I remember one morning getting up at dawn, there was such a sense of possibility. You know, that feeling? And I remember thinking to myself: So, this is the beginning of happiness. This is where it starts. And of course there will always be more. It never occurred to me it wasn't the beginning. It was happiness. It was the moment. Right then.” It is a reminder to us to embrace those islands of calm and joy and happiness in our own life, to not let ourselves become so caught up in our longings for what-might-have-been or what-might-be that we forget to simply enjoy the present as-it-is.

Ever since I watched the film, and even more since I recorded a podcast about it, I’ve wondered what it is about it that stirred so many deep feelings within me. To be sure, I’m a film viewer who loves to feel, and I’m particularly drawn to those films that make me feel sad or which stick with me. The whole time I was watching it, I felt something, though it often lurked beneath the surface (here the score comes into play. Throughout the film, it haunts the narrative like a seething unconscious, often expressing the repression the characters themselves struggle to satisfactorily convey to others). It was only after I’d sat with it for a while, though, that I came to some important conclusions.

Ultimately, I think, the film resonates with me because I’m now within spitting distance of 40 and, like the women of The Hours, I find myself increasingly thinking about all of the lives I might have led, longing, maybe, for some other future than the one I now face. It’s not that I’m not happy, because I am. But there’s no doubt that, when I was younger, I envisioned being something different than I am now. I imagined being a successful writer, having a book published, being on the tenure track. Some of these things are still possible, of course, but others are not. Just as there are many loves I’ve had to leave behind, so I have also had to let go of my dream of being a professor.

However, if The Hours has taught me anything, it’s that you have to make your own happiness in the world. I’ll never be free of the longing, but I no longer let it imprison me. We only have so many hours in this world, and I intend to make the most of them.

If you like what you read here at Omnivorous, including this little essay, then please consider subscribing. There are both free and paid options, and we’d love to have you!

Very well expressed Dr. Thomas. I like the way movie made me ride through multiple emotions - from hatred towards Laura to advocating for her ‘choice of freedom’. Virginia’s words in the station haunts me for the sheer truth it expresses - nobody can ever feel or sense the real emotions within us, it requires a vision deeper than what just love can bring. But Richie had it - he felt and sensed what his mother was going through, even though she covered it with smiles and decorative words.