The Enduring Relevance of "Island of Lost Souls" (1932)

The 1930s adaptation of H.G. Wells' classic novel is a timely warning of the dangers of humanity's seemingly inexhaustible hubris.

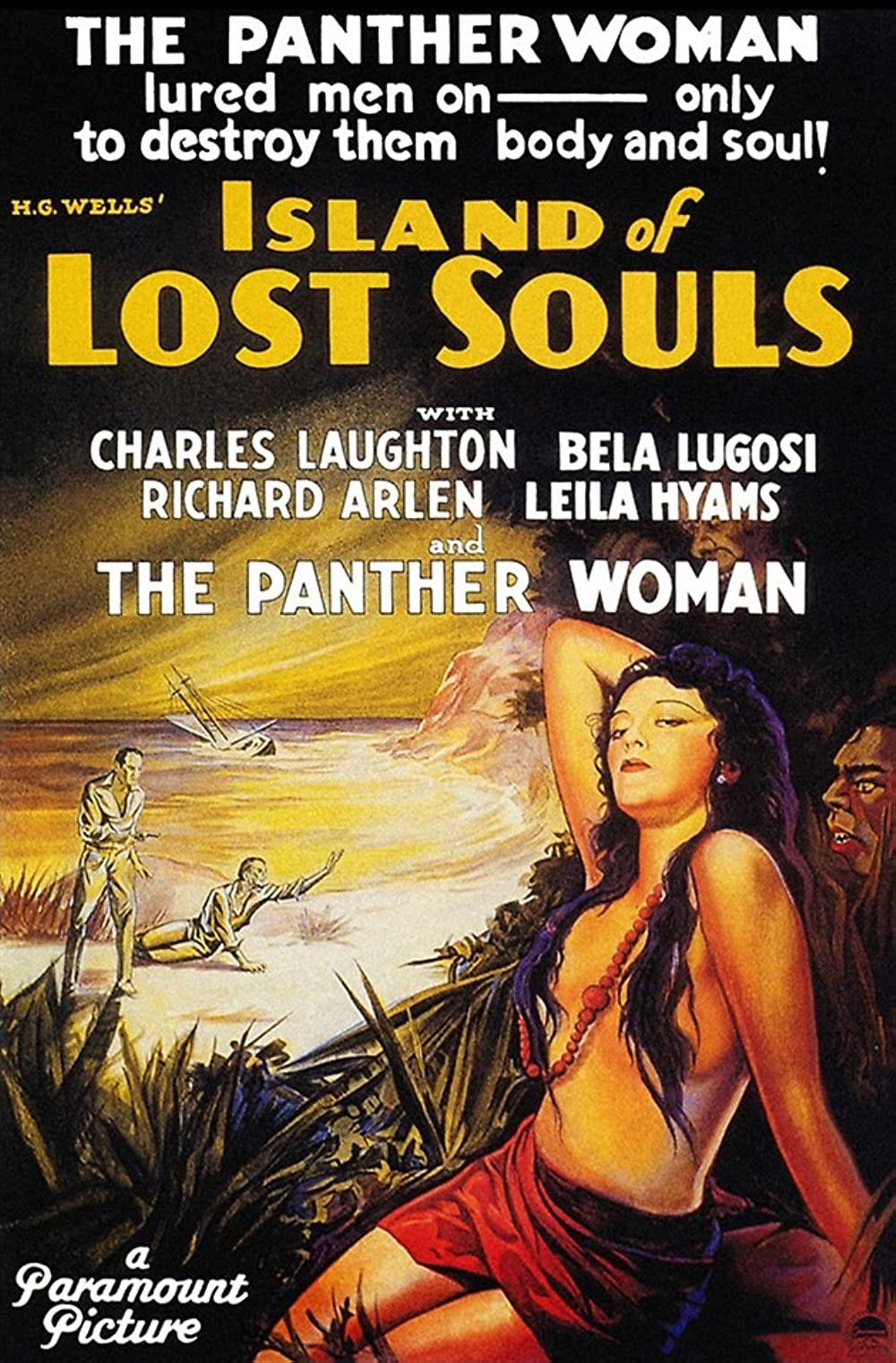

I’ve always been morbidly fascinated by H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreau. There is something deeply disturbing–and alluring–about the idea of the specter of the human/animal hybrid, and it’s been an abiding interest of mine since I was in graduate school. I’ve been particularly drawn to the representation of such beings in the cinema, and Island has been adapted several times. During a recent visit to my parents’ house, my mother decided to watch The Island of Lost Souls, the 1932 adaptation of Wells’ adaptation and, since I’d never seen it (though I have seen the truly bonkers 1996 version starring none other than Marlon Brando as the titular doctor), I figured this was as good a time as any.

If you haven’t seen the film or read the original novel, the story is fairly simple. An Englishman Edward Parker, finds himself stranded on an island inhabited by one Dr. Moreau, who essentially runs the island as his own personal fief. Having fled into exile from his native England, he has pursued a number of sinister experiments, creating a strange and terrifying race of human/animal hybrids. However, Parker proves to be something of an agent of chaos in Moreau’s kingdom, and it’s not long before the creatures are rebelling against their maker, dismembering him with his own knives, a fitting punishment for a man who has committed his life to bringing pain and misery to others in the pursuit of “knowledge.”

It’s a lean little film, running just over an hour (it has endured a number of cuts throughout the years). Nevertheless, there are some strong performances from the cast, including from Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law, a sort of priestly figure who serves as the leader of the animal-men. There’s no doubt, though, that Charles Laughton is the undisputed star of the film. I’ve long been an admirer of Laughton’s, and there are few actors of the classic Hollywood period who could act in almost any genre, including swashbuckling dramas (Mutiny on the Bounty), decadent biblical epics (The Sign of the Cross), and courtroom dramas (Witness for the Prosecution). No matter what role he appeared in, he knew how to make the most of it.

As Moreau, he ably captures the character’s brutal and sinister and deeply cynical outlook on the world. He is the ideal British colonial mind, someone who believes that his own natural genius entitles him to use and abuse his creations, imposing on them a system of rules he has no obligation to follow himself. He even goes so far as to use Lota, “The Panther Woman” to try to seduce Parker, in the hopes of being able to observe his most human-like creation. For Moreau, nothing matters except the procurement of more knowledge (and thus more power), no matter how many lives or people he has to hurt in the process. Like rapacious minds throughout the ages–including in today’s Silicon Valley–he believes that progress is a laudable goal in itself, without any further self-examination of his motives or the consequences of his studies.

Thus, what really stood out to me about the film was just how relevant it felt, no small thing for a popular culture text that is now almost 100 years old. In an age in which AI has become increasingly sophisticated and has begun to blur the already-porous boundary between the human and the animal, The Island of Lost Souls is a film with a timely message, particularly about the danger of creating things that begin to take on their own consciousness and slip out of the control of their supposed “masters.” As the film reaches its hysterical climax, Moreau desperately tries to hold his creations at bay, bellowing at them to remember the laws he has relentlessly imposed on them and cracking a whip. However, the tools of oppression no longer suffice to keep the subalterns in line and, given their sheer numbers, it’s not long before they have completely overwhelmed him. It’s hard not to feel that his dismemberment at their hands is a fitting punishment for someone who thought so little of the lives he created that he sentenced the “failures” to provide power for the rest of the island.

Watching the film in 2023, one can’t help but wonder: at what point will our digital creations, already so lifelike, begin to gain the kind of consciousness and sense of self-awareness as Moreau’s hybrids? Once they do, what’s to stop them from undertaking the dismemberment of their creators? Already, we’re seeing AI touted as a potential death-knell for all sorts of creative professions, now that anyone with the access to a Chatbot can supposedly engage in the act of creation. Just recently, a prominent magazine that publishes original science fiction and fantasy short stories had to close their submissions because they were quite simply overwhelmed by AI-generated submissions. At the risk of sounding alarmist, it’s becoming ever easier to see a future all too familiar from such iconic films as The Matrix and Terminator. After all, if we’re willing to surrender our creativity to artificial intelligence, what else is left to mark our fundamental humanity?

Unlike Edward Parker and his companions, however, we don’t have the option of simply turning away from the conflagration burning behind us, as they do in the film’s finale, leaving behind Moreau’s island engulfed in flames, its animalistic residents condemned to a perpetual twilight existence. We must face, in a way that Moreau is never quite willing to do, the consequences of our actions and the wages of our technological sins. We must address head-on the challenges and the promises posed by AI, as well as whatever other advances the tech bros of Silicon Valley see fit to inflict on the rest of us. If we don’t, then perhaps we will deserve the fate that is meted out to Dr. Moreau, a man who is so consumed with his own hubristic vision of the future he cannot see his death coming until it is far too late.

Let’s hope the same does not happen to us.