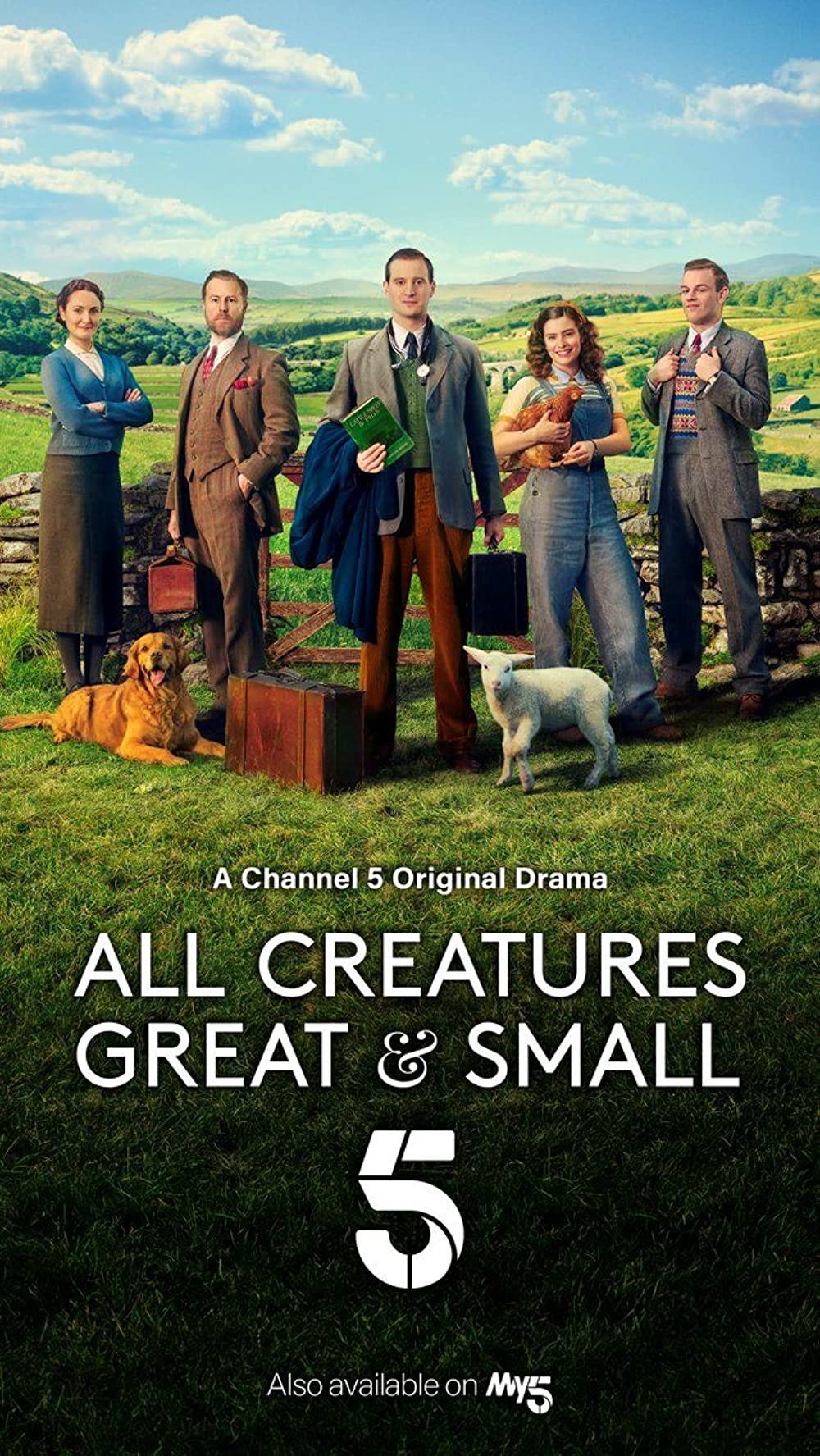

The Emotional Maturity of "All Creatures Great and Small"

The popular feel-good series has grown into itself and is now one of the best series currently on television.

I think it’s safe to say that All Creatures Great and Small is one of my favorite things on television right now. I’ve always found the works of James Herriot to be uniquely poignant and touching (perhaps it’s my own upbringing on a farm), and I have fond memories of watching the 1970s/1980s serial with my mom as a child. When I watched the first two seasons of this new adaptation, I didn’t quite know what to expect, but it wasn’t long before I fell under the series’ unique enchantment. I was, and am, impressed with the skill with which this new version manages to weave in a number of the stories related by Herriot in his original novels–which are, really, more like collections of short stories than traditional novels with a linear narrative–while also creating an equally compelling serial drama.

If anything, the third season is even more emotionally devastating than the first two, and I definitely mean that as a compliment. Even though All Creatures Great and Small hit the ground running, there’s no question that it has continued to gain in emotional maturity during the course of its three seasons, using the expanded canvass provided by more seasons (it’s already been renewed for a fourth) to dive more deeply into the hearts, minds, and motivations of our beloved characters. As season 3 progresses, they each find themselves challenged in ways they could never have imagined.

For the world that this season takes place in is one that is increasingly facing the prospect of another global conflict, one that could be even more devastating than the previous one. Indeed, the specter of the First World War looms large over all of the characters in one way or another, but it has a particularly strong impact on Siegfried Farnon and Mrs. Hall. For the former, it takes the form of a former comrade-in-arms who takes his own life, as well as a horse whose resistance to being trained (attributable to trauma) reminds him of the horses he helped save on the fields of war, only to have to destroy them at the government’s orders. This act of betrayal clearly still haunts him, and it helps to explain his commitment to helping a horse recover its equanimity.

At the same time, it also affects his relationship with Tristan. The two have always had a fraught dynamic, largely because the younger Farnon refuses to fit the mold his older brother has prescribed for him. Now, things are further complicated by Sigfried’s determination to keep Tristan from encountering the brutality and ugliness of the battlefield, no matter what he might want. This all comes to a head during the Christmas special, When Siegfried ill-advisedly puts a horse’s life at risk, so he can call in a favor and help Tristna to defer his enlistment (this is an excellent example of the series’ ability to weave together its animal and human storylines). Predictably, this leads to a taut confrontation between the two men, in which Siegfried finally admits that, though he loves Tristan, he’s always resented him for being his parents’ favorite. Both Samuel West and Callum Woodhouse dig deep in these moments, bringing up years’ worth of pain and disagreement, even as it’s also clear just how much they truly love each other. Their scene at the train station, when Tristan at least leaves for an uncertain future in the army, is heartbreaking and touching and beautiful, all at once.

For Mrs. Hall, meanwhile, the shadow of World War I manifests as her desire to maintain her fragile state of peace at Skeldale House, which is a bit of an oasis in what has been a chaotic life. After all, her husband, who she continues to insist was a good man, had his life ruined by the Great War, leading to alcohol abuse and a collapsed marriage. Her yearning to keep things as they are means that she keeps her beau Gerald at arms’-length, even though it’s clear to everyone just how much they share and how obvious the connection between them. Slowly but surely, however, Mrs. Hall realizes that she is making a mistake in pushing him away and that her past shouldn’t keep her from embracing the pleasures of the future.

Arguably the most heart wrenching Mrs. Hall scene comes in the fifth episode, aptly titled “Edward.” As its title implies, this episode focuses a great deal on her long-belated reunion with her estranged son, Edward. Viewers will recall that the cause of their falling-out was due to her turning him in to the police for stealing from her employer. After keeping her waiting at the train station for a very long period of time the two finally meet, and it’s clear right away that Edward harbors a lot of resentment for his mother, and he spurns almost all of her efforts at reconciliation (including turning his nose up at some treats she made especially for him). For her part, Mrs. Hall tries, desperately, to break through his brittle reserve and, thanks to Anna Madeley, it’s a performance which will, I think, come to be seen as among the best of her career.

By this point, I think it’s pretty clear that Mrs. Hall is one of the best characters in the entire series, the beating heart at the center of Skeldale House, the one person that everyone knows they can rely on. Here, however, she shows just how vulnerable she is, and how gracious. Despite Edward’s initial refusal of her offers of rapprochement, she persists, telling him that she loves him and has always seen the good in him, even when she was powerless to help him realize it himself. She even goes so far as to apologize for turning him in to the police (even though she was absolutely right to do so, in my humble opinion). Madeley allows us to see the raw pain of a mother who was at her wit’s end and who did the only thing she thought might work to bring her son back from the brink. By the time that Edward departs, it’s unclear as to whether they will ever be able to make it past the past, particularly since he continues to believe that her decision to turn him into the police destroyed whatever good was left in him.

If, like me, your relationship with your mother has been strained at times, then this episode is sure to hit you right in the feels. Fortunately, this is All Creatures Great and Small, a show that is all about the power of grace and kindness and so as the train pulls away, Edward calls out that he loves her. However, she only knows this because a young deaf woman she has befriended has the ability to read lips. The look of mingled joy and sorrow on Mrs. Hall’s face is a poignant, and fitting, conclusion to this exchange. As so often in this series, there is no easy answer, much as we (and Mrs. Hall) might wish it were otherwise. Like Siegfried, she’s come to realize that she has to let Edward find his own way in the world and, just as importantly, back to her.

The pathos of this episode is also bolstered by the young deaf woman who befriends Mrs. Hall at the train station, offering her a cup of tea while she’s waiting. I’ve always appreciated the ways that All Creatures Great and Small manages to have these quiet moments of representation. In earlier seasons, we met a Black woman married to one of the Yorkshire farmers, who spoke about what it was like to come from a major urban center to what was, essentially, the middle of nowhere. The series doesn’t beat you over the head with these moments; instead, it allows them to unfold graciously and naturally, allowing us to see that pre-World World II was a diverse and multicultural place, however much a certain kind of white nationalist nostalgia might wish it were otherwise.

Lest you think that All Creatures Great and Small neglects the creaturely parts of the story, rest assured, there are many touching, and sometimes quietly devastating, incidents. Among other things, the practice faces a number of key challenges for, as always, the farmers in the Yorkshire Dales are, on the whole, a conservative and stubborn bunch, not willing to change things unless they absolutely have to do so. In another moving episode, an old farmer’s calves start to fall ill and die and, after much head-scratching by Siegfried and James, it’s discovered that she’d been treating them with a poison melt to kill bugs but which has also gotten into their drinking water. The reason she didn’t realize this? Because she can’t read and, while her sister can, the two haven’t spoken since the latter moved to the next farm over after getting married. Finally, she realizes that her stubbornness has cost her not only her relationship with her sister but also her beloved calves, and so she sets out to make things right. As so often in the series, the animal and the human stories seamlessly blend which is entirely appropriate, given that this is the reality for those who make animals such a key part of their lives.

As I noted about the first season, one of the things I appreciate about this series is the sensitivity with which it treats agricultural life and the struggles that small farmers face as they attempt to make a life for themselves from the land itself. This season shows James particularly committed to TB testing, a measure which many farmers oppose because, among other things, it means that the government can both take their animals and shut their farms down if one of their cattle turns out positive. This all becomes very personal for James when, unsurprisingly, one of his father-in-law's cattle turns out positive, leading to all sorts of moral (and practical) complications for all of them.

By far the greatest burden for our beloved vet, however, is the pressure to sign up to fight in the impending war. From the beginning of the season, he feels the urge to do his part, not only to defend his country but also to defend Helen and the life that they’ve built together. Yes, he could accept the fact that, as a vet, he is one of those who is exempt and yes, it is true that Helen and Siegfried and all of the others need him, but it’s clear that avoiding service–even for the noblest of reasons–just isn’t the type of person James is. As Tristan trenchantly remarks, his restless do-gooder spirit is going to get him killed if he’s not careful. Given that at least another season is in the offing, we’ll likely have an opportunity to see how James deals with the pressures of serving in the military, if it should come to that.

For all that it is one of those series designed to make the viewer feel better about the world and their place in it, All Creatures Great and Small is also about the fraught choices that people often have to make during the course of their lives. The stories can sometimes feel a bit isolated and parochial, but for the characters involved these are quite literally matters of life and death. If, like me, you grew up in a small town and rural area not all that much different from the Yorkshire Dales, some of these stories will no doubt resonate with you. More to the point, the series has gained a deeper emotional resonance as it has gone on. It knows how to find just the right balance between happiness and sadness, between the animal and the human, and between the past and the present. Far more than just a comfort show, All Creatures Great and Small is a reflection on the choices that people make as they face a world increasingly destabilized and uncertain. In that sense, it is very much a balm for the soul, and a reminder to all of us, in this perilous present of ours, of the power of hope.