The De-Queering of Baron Harkonnen

In stripping away the queerness of one of sci-fi's great villains, Denis Villeneveu's "Dune" removes what makes the Baron so fascinating, and so troubling.

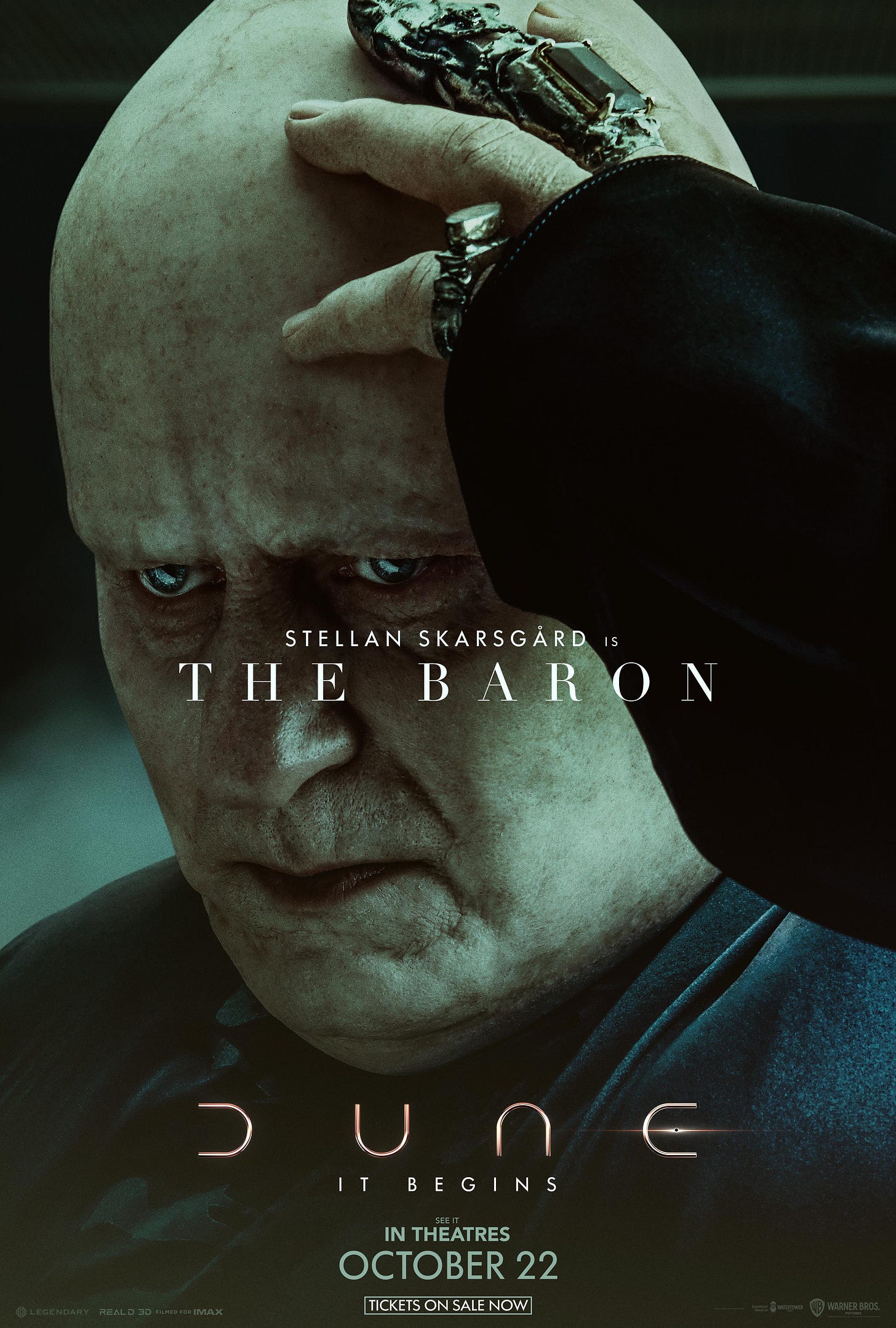

Well, it’s finally here. The trailer for the highly-anticipated Dune: Part 2 has now dropped, giving us our first looks at such beloved characters as Princess Irulan and Feyd-Rautha, the latter of whom looks like he is going to be even more unhinged than he is in the novel (and, if you’ve read Herbert’s book, you know that’s no small thing). We’re also graced with a few more glances at Stellan Skarsgård as Baron Harkonnen, the devoted enemy of House Atreides and the architect of their destruction.

There’s no question that Skarsgård is sublime as the Baron. Brooding and sinister and gravelly-voiced, he’s a far cry from either the high camp antics of Ian McNeice (who played him in the Syfy miniseries) or the viscerally disgusting and disfigured performance of Kenneth McMillan (in David Lynch’s infamous 1984 adaptation). Rather than a stereotype or a farce, he is instead just the type of person you can well imagine pulling the levers of power, doing whatever it takes to destroy his family’s age-old enemy. The scene in which he gloats over the prostrate form of the dying Duke Leto will forever be etched in my memory.

However, there is one thing conspicuously missing from this depiction of the Baron, and it’s arguably one of the most notable things about him as he appears in the novel: namely, his queerness. As has been amply documented, Herbert’s vision of the Baron was a horrific distillation of every prevailing cultural stereotype of the homosexual. He’s a sadistic pedophile whose avaricious desire for nubile male flesh extends even to Paul and his own nephew Feyd-Rautha, someone for whom, indeed, the cruelty is the point. Herbert’s novel dwells with almost lurid fascination on the various cruelties of which he’s capable, and his death at the hands of his own granddaughter, Alia, is viewed as just punishment for his depravity.

Both the Syfy miniseries and, more perniciously, Lynch’s film maintains the Baron’s queerness, though in this regard Lynch’s film is particularly jarring. His vision of Vladimir Harkonnen is horrific in all of the worst ways and, among other things, his version of the character is afflicted with suppurating boils on his body, a grotesque and horrifying stigmata that many have seen as a clear allusion to the AIDS crisis then afflicting the gay community.

Compared to these excesses, Villeneuve’s Baron is positively demure. Yes, he is still the hulking, obese being he was in the novel and, as his gloating over Leto’s death reveals, there’s still much of the sadist in him. From the director’s point of view, however, excising the queer elements was, contradictory though it might seem, a way of fleshing out the Baron in other ways, removing those things that made him almost a caricature. In doing so, however, Villeneuve has also removed that which made the Baron so compelling and, moreover, it removes the novel’s own internal criticism of its own project.

As anyone who has read Dune knows, this entire universe is one predicated on the importance of heritage, of legacy, and of biological inheritance. The whole reason that Paul is this series’ chosen one is because he is the end result of a generations-long breeding program instituted and maintained by the matriarchal Bene Gesserit. The Baron has also had his part to play in this but, in both Frank Herbert’s original novel and in the prequels he is also a source of potential disruption. The Baron is steadfastly opposed to all of that, precisely because his perverse desires are the very antithesis of the heteroreproductive, forward-looking thrust of Dune’s narrative. Even the revelation that the Baron is, in fact, the father of Lady Jessica–and thus Paul’s maternal grandfather–isn’t quite enough to rescue him from the abject position of the future-denying queer.

And, though he dies at the end of Dune–dispatched by his own granddaughter, the misbegotten Alia–he later makes a return of sorts, as one of the ancestral memories with which she has been blessed (or cursed). Like the return of the repressed, he slowly takes over his granddaughter’s consciousness, finding new life and purpose in manipulating her to his own endlessly nefarious ends. Only her suicide prevents him from taking over completely, yet another strong association of the Baron with a genetic dead-end.

Whatever Herbert’s homophobic intentions, the Baron ultimately emerges not just as a potent criticism of the novel’s central heterocentrism; his chapters are the most fascinating in the book. While so much of Paul’s story is either motivated by his chosen one story arc or by endless descriptions of Arrakis and its desolate landscapes, the Baron is always enmeshed in the labyrinthine politics of the Imperium. And, like so many of the great queers of popular culture, his is a sardonic narrational voice, with a wry and ironic detachment that is in marked contrast to his debauched actions and political ruthlessness. However great Stellan Skarsgård may be, and however masterful Denis Villeneuve’s direction, neither quite captures what made the Baron such a fascinating villain.

Nor is the Baron the only example of our culture’s resolute de-queering of its villain. One need look no further than the various live-action Disney remakes to see how this has been played out. Scar, Jafar, and Maleficent are all significantly less queer than their animated forebears and, it has to be said, they’re also far less interesting. On the one hand, it’s easy to see why this development is a good thing. For better or worse, culture impacts how we perceive others, and it’s probably not a good thing that for most of the history of cinema and popular culture queer people have been pathologized and rendered monstrous. It’s far easier to deny people their rights and essential dignity when you’ve been trained to see them as less than human.

On the other hand, I can’t help but wonder if we’re also losing something with this de-queering of villainy. In the cultural imaginary queerness is always dangerous, yes, and it must be punished and, if possible, expelled from the narrative (and thus, symbolically, from the social fabric). At the same time, queerness is also alluring and dangerous and seductive. Characters like the Baron and his ilk remind us that there are other ways of being in the world, that we all don’t have to follow the dictates of heterosexuality or “chosen one” narratives. Lacking this bite, the Baron is just another sci-fi heavy, and the genre, and all of us, are poorer for it.

Wow. I was just about to post a blog about Dune and decided to google this first. Your SubStack popped up. Yes it had struck me that while new politically correct reboots of old IPs often re-imagine straight characters as gay or White characters as Black, this was the first time I saw a gay character re-imagined as straight -- because, let's face it, they were afraid of a woke backlash. He is still depicted as a sexual sadist but he has slave girls instead of slave boys. As a culture we have come to a point with racism that we can have a Black villain in a Marvel film but we can still not have a gay villain in a blockbuster. The pedo association that is often used to smear gays makes this complicated. Also, some of the best scenes from the books where him discussing his political calculations with his nephew. These were missed from the movie.

This is one of the most useless things I have ever read. Took no position, understood very little about dune, and not to mention pop culture and the world around us. Please try to remove your head from your ass and touch grass.