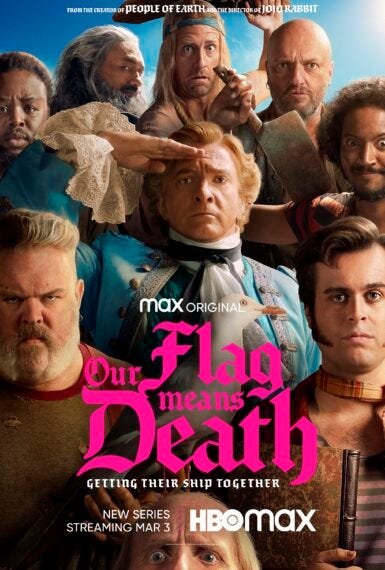

The Charming Queer Tragedy of "Our Flag Means Death"

The HBO Max series uses a story of two pirates in love to create a story that is equally parts enchanting and tragic.

When I first started watching Our Flag Means Death, I wasn’t exactly sure what I was in for. At first, I thought it was a charming and quite funny mix of Muppet Treasure Island and What We Do in the Shadows. Slowly but surely, however, it revealed a subtle richness, particularly in the way it chose to handle its numerous queer relationships, whether the odd but somehow touching bond between the gruff and at-times irritating Black Pete and the fussy scribe Lucius or the deep well of feeling that slowly emerges between Oluwande and Jim, the series’ notably nonbinary character.

There’s no question, however, that the most important queer relationship is the one between Rhys Darby’s Steve Bonnet (known as “The Gentleman Pirate”) and the Taika Waititi’s infamous (and quite ruthless) Blackbeard. As the season proceeds, the two men each find in the other their perfect complement, with Blackbeard’s roughness providing Stede an escape from his mediocre aristocratic life and Stede providing Blackbeard a love and compassion he has formerly lacked. At first, neither seems quite sure what to make of the other, but slowly but surely a beautiful romance blossoms between these two pirates on the high seas.

However, all is not well for the lovebirds, and numerous forces conspire to tear them apart, most notably Blackbeard’s first mate Izzy, a gravelly-voiced manipulator who has nothing but contempt for Stede (and for anyone who doesn’t adhere to what his idea of a man should look like). After Stede seemingly abandons Blackbeard to resume life with his family, Izzy takes this as an opportunity to ruthlessly mock his captain until he cuts all ties with his former life: he throws his books overboard, seemingly drowns the flamboyantly gay pirate Lucius, and abandons most of Stede’s crew on a desert island. However, though Blackbeard has been driven to a cruelly deranged madness by Izzy’s homophobic cruelty, it’s clear he still has feelings for Stede.

Much has already been written about how the series challenges and rejects the queer baiting so common in television, and the Blackbead/Bonnet ship has already begun to take Twitter by storm (go check out some of the truly fantastic fan art). What stuck out to me, however, was how neatly their story both adhered to and yet charmingly subverted the queer tragedy narrative which is also so ubiquitous in television (particularly those series set in the past). There is, indeed, something almost Shakespearean about the way Izzy conspires, Iago-like, to drive a wedge between Blackbeard and Stede, preying on the former’s deep-rooted insecurities, particularly surrounding his masculinity to force his hand into becoming the nefarious and bloodthirsty pirate he believes he should be.

Taika Waititi deserves a tremendous amount of credit for his performance. He successfully teases out all of the complexities of a man like Blackbeard: a young man who killed his own abusive father, a brutal pirate capable of cutting off a man’s toe and feeding it to him (which he does to Izzy in the final episode), a sensitive soul who yearns for a life beyond the rapacious brutalizer he’s slowly become. When, in the finale, we see him weeping in despair at the loss of his beloved, it’s one of the most heartbreaking moments in recent television.

And has there ever been a pirate hero more deliciously and charmingly tragic than Stede Bonnet himself? Fey and emotionally overwrought he might be, but he is still a genuinely good man, someone who cares for his crew and their emotional well-being and someone who desperately yearns for a happiness which always seems to elude him. Only when he meets Blackbeard does he seem to find some measure of completeness, and there is something very endearing about how desperate he is to impress the other man, just as Blackbeard’s child-like glee at planning their getaway tears at the heart. When they kiss on the beach–dreaming of running away to China and starting their lives anew–you can’t help but weep, even as a part of you knows it can’t and won’t end well.

Because the truth is that Stede is, when it comes right down to it, a man of conscience, and he can’t start a future with Blackbeard until he has at least tried to restore the family he left to pursue his life of piracy. To his dismay, he finds his wife content with her life as a widow–replete with a physically satisfying relationship with her art instructor–and he finally has to accept the reality that his old life has no room for him. What makes this whole sequence even more tragic, however, is his recognition that Blackbeard is the love of his life takes place at the exact same time as Blackbeard is doing everything in his power to disavow his own love of Stede. Neither man realizes the truth of matters, and so the stage is set for a potentially fatal encounter between the two men.

In a less capable show, this entire arc would feel like just another queer tragedy, in which two queer characters find themselves driven apart, unable to ever fully live their lives and loves authentically. Two things, however, save Our Flag Means Death from this fate. First, there’s the simple charm of the show. It’s the kind of series that makes you love the characters, with a twinkling and infectious sense of humor which proves impossible to resist. Second, there’s the fact that the tragedy makes sense for these characters. Everything that takes place during the finale–Stede’s recognition of his love for Blackbeard, Blackbeard’s rejection of his emotional side–is the logical fulfillment of what’s come before. Just as importantly, their tragedy doesn’t happen because they’re queer; it happens because they’re too people with their own tragic flaws: Stede’s frustrating sense of honor and Blackbeard’s inability to come to terms with his own traumatic past.

I honestly have no idea what lies in store for these beloved queer characters, whether Stede will reunite with Blackbeard and all will be forgiven or whether their story will end truly tragically. No matter how it ends, however, I know that I, for one, will be watching.