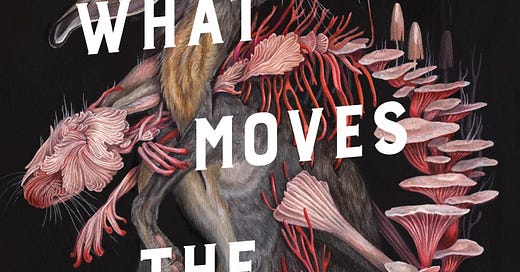

Terror Tuesday Book Review: "What Moves the Dead"

T. Kingfisher's reimagining of "The Fall of the House of Usher" forces us to reckon with the permeability and instability of the human body.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Just a reminder that I’m running a special promotion here at Omnivorous for the whole month of May. If you join as a paid subscriber, you’ll be entered into a raffle to win a gift card to The Buzzed Word, a great indie bookshop in Ocean City, MD. Check out this post for the full details!

Warning: Full spoilers for the book follow.

For the inaugural entry of “Terror Tuesday,” I want to talk about T. Kingfisher’s What Moves the Dead. This was our monthly read for my local queer book club, and as soon as I read that it’s a queer imagining of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” I knew that I was going to love it. Indeed, this is the kind of creepy, atmospheric horror that I love, leavened with a protagonist whose dry wit keeps the novella from becoming overwhelmingly terrifying.

When the book begins Alex Easton, a sworn soldier of the Gallacian army, is on his way to visit Roderick and Madeline Usher, childhood friends of theirs. As soon as they arrive, however, it is clear that something is amiss with both of the Usher siblings, though Madeline is clearly suffering the most from some mysterious affliction. As the novel goes on, Easton–along with an intrepid British mycologist named Mrs. Potter, his Scottish batman Angus, and an American doctor named Denton–discovers that Madeline has been infected by a fungus dwelling in the nearby Tarn and, as a result, is a threat to both those in the house and the lands nearby. In the end they manage to destroy it and the Usher house, but only at the cost of both the siblings, who perish in the flames that consume their crumbling home.

I know that fungal horror is very much all the rage right now, but no matter how many iterations of it I read about it never ceases to terrify me. I don’t know if it’s because fungi seem so much more tangible than, say, viruses or bacteria, or if it’s because they are just so damned hard to eradicate from our bodies–anyone who has had a case of athlete’s foot or jock itch can testify to this–but these little beings are chilling reminders that humans aren’t as firm in their position at the top of the food chain as they might like to believe and that the human body is just as susceptible to invasion as anything else in nature. Moreover, as Mrs. Potter reminds Easton, the reality is that fungi are literally everywhere all the time, their little spores just waiting for the chance to invade our bodies.

This horror grows exponentially when one thinks about those species of fungus that can take control of other beings in order to propagate themselves, which is exactly what happens to poor Madeline Usher. These entities might lack consciousness as we normally think of such a thing, but they have an ability to essentially hijack other beings to serve their will. This is certainly true of Madeline, whose body has been taken over by the being after having drowned in the lake. This whole revelation, while explaining why it is that she has been acting so strangely, also opens up a whole new series of chilling and disturbing questions. Chief among these is: to what extent is this woman wandering the halls and speaking in a strange way actually Madeline and how much is it just the fungus using her for its own purposes? Is there anything left of Madeline’s soul in this filament-riddled corpse? The fact that the novella doesn’t really answer this question–deliberately so, I think–is one of its most terrifying elements.

I’ve seen some criticisms that the gender play in the book feels forced or is somehow an imposition on Poe’s text. In my opinion this couldn’t be more wrong. Not only is it interwoven into the very world that this novella creates, it also serves as a key connection between Easton and the sinister fungus that has taken over the tarn. Both of them, after all, exist outside of the gender norms that so often govern how people look at themselves and the world around them. Furthermore, when Madeline refers to the fungus growing inside of her and motivating her body with the pronoun that the Gallacians use to refer to children, it says a great deal about how she conceives of this being or, more sinisterly perhaps, how it conceives of itself. If, indeed, it is a child, then it’s a very powerful one and, as J.M. Barrie might put it, heartless, in the sense that it has yet to develop a sense of empathy or the other pesky human emotions that might keep it from taking over the other organisms with whom it comes into contact. It contains multitudes, and therein lies its horror.

Indeed, one of the most chilling passages in the book occurs when Easton, unable to sleep, wanders out to his balcony and looks out on the tarn, where he sees a multitude of lights shining in its murky depths. This beauty is exactly what makes the tarn and its fungal inhabitant so absolutely terrifying. It’s easy to see why Madeline would feel so drawn to this being, this thing that is so horrifyingly other yet also so uncannily like. While What Moves the Dead has far more in common with gothic horror than it does with cosmic horror, one still gets the sense that there lurks, in the dark waters of the tarn, a being that is so far beyond the human that it can never be fully comprehended. It bears humanity no ill-will but, instead, is simply trying to grope its way forward in this strange and brave new world.

Equally disturbing, I think, are the hares, who were the fungus’ first experiments when it came to experiencing the world of conscious creatures. By themselves hares aren’t particularly terrifying creatures but, when they’re under the command of a fungus that is suddenly bent on expanding its reach and perhaps taking over everything that’s nearby, they take on an eldritch and uncanny quality (in the Freudian sense that they are familiar but have been made utterly strange). Adding to the grotesquery is the fact that they are almost impossible to kill. Not even a gunshot to the head is enough to destroy them, which says a great deal about how powerful this fungus is and how much of a threat it poses not just to the Ushers and their guests but also to anyone else who might be able to come in contact with it.

In the end, What Moves the Dead leaves us with a sense of profound unease. The fungus has been destroyed, and the two Ushers have been consigned to the flames, but at what cost? Can we as humans really blame the fungus for simply trying to survive and evolve, even if humans and hares were caught in the crosshairs? As Easton constantly reminds us, the human world is one of war and conquest and death, so really, couldn’t we do worse than to be colonized by a fungus?

Like all great horror, What Moves the Dead asks us these questions but leaves us without sure answers. We must instead sit with our discomfort and our unease. And we must also, of course, pick up the sequel, What Feasts at Night.

![What Moves the Dead [Book] What Moves the Dead [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GqcO!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8b7a3e6e-0230-458d-add8-973e9cde67ff_1547x2474.jpeg)