Sinful Sunday: Violence and the Specter of Queer Desire in "Magazine Dreams

The Jonathan Majors vehicle plunges the dark depths of the male mind in order to show how queer desire remains the specter from which it cannot escape.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

As an added bonus, every month I’ll be running a promotion where everyone who signs up for a paid subscription will be entered into a contest to win TWO of the books I review during a given month. For April, this will include all books reviewed during March and April. Be sure to spread the word!

Welcome to “Sinful Sundays,” where I explore and analyze some of the most notorious queer villains of film and TV (and sometimes literature, depending on my mood). These are the characters that entrance and entertain and revolt us, sometimes all three at the same time. As these queer villains show, very often it’s sweetly good to be bitterly bad.

Magazine Dreams is, I think it’s safe to say, one of the strangest and most viscerally disturbing films of 2025 (yes, I know the year is young, but if you’ve seen the film you’ll know that I’m not exaggerating). In part, this stems from the fact that its story–about an amateur bodybuilder who becomes so enmeshed in his desire to create the perfect body that he turns increasingly to violence–has so many chilling similarities to the real-life behavior of its star, Jonathan Majors. In case you’ve been living under a rock for the past couple of years, the once promising star was accused of assaulting his girlfriend and was ultimately found guilty of misdemeanor assault and harassment. It’s one of those strange confluences in which a star’s life comes to strangely mirror that of the films in which they appear.

Majors stars as Killian Maddox who, though a grocery store worker, yearns more than anything else to be the best bodybuilder in the world. To this end he repeatedly subjects his body to the rigors of training and steroids, even as doing so leads to increasingly erratic and dangerous behavior. At the same time as he lashes out at everyone–with the exception of his grandfather, with whom he lives, and a coworker on whom he harbors a rather awkward crush–he also writes impassioned and obsessive letters to world-renowned bodybuilder Brad Vanderhorn (Mike O’Hearn). Though the two end up meeting and sharing a strangely intimate moment (more on that in a moment), in the end Killian ends up giving up his dreams, though it remains unclear whether his unsettled psyche will ever really return to a state of equilibrium, if indeed it ever existed in such a state.

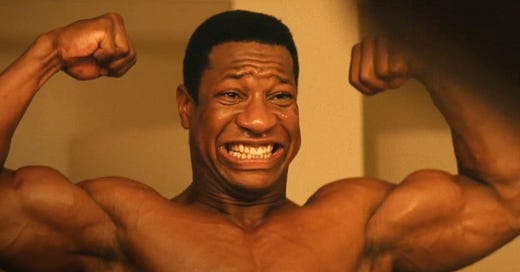

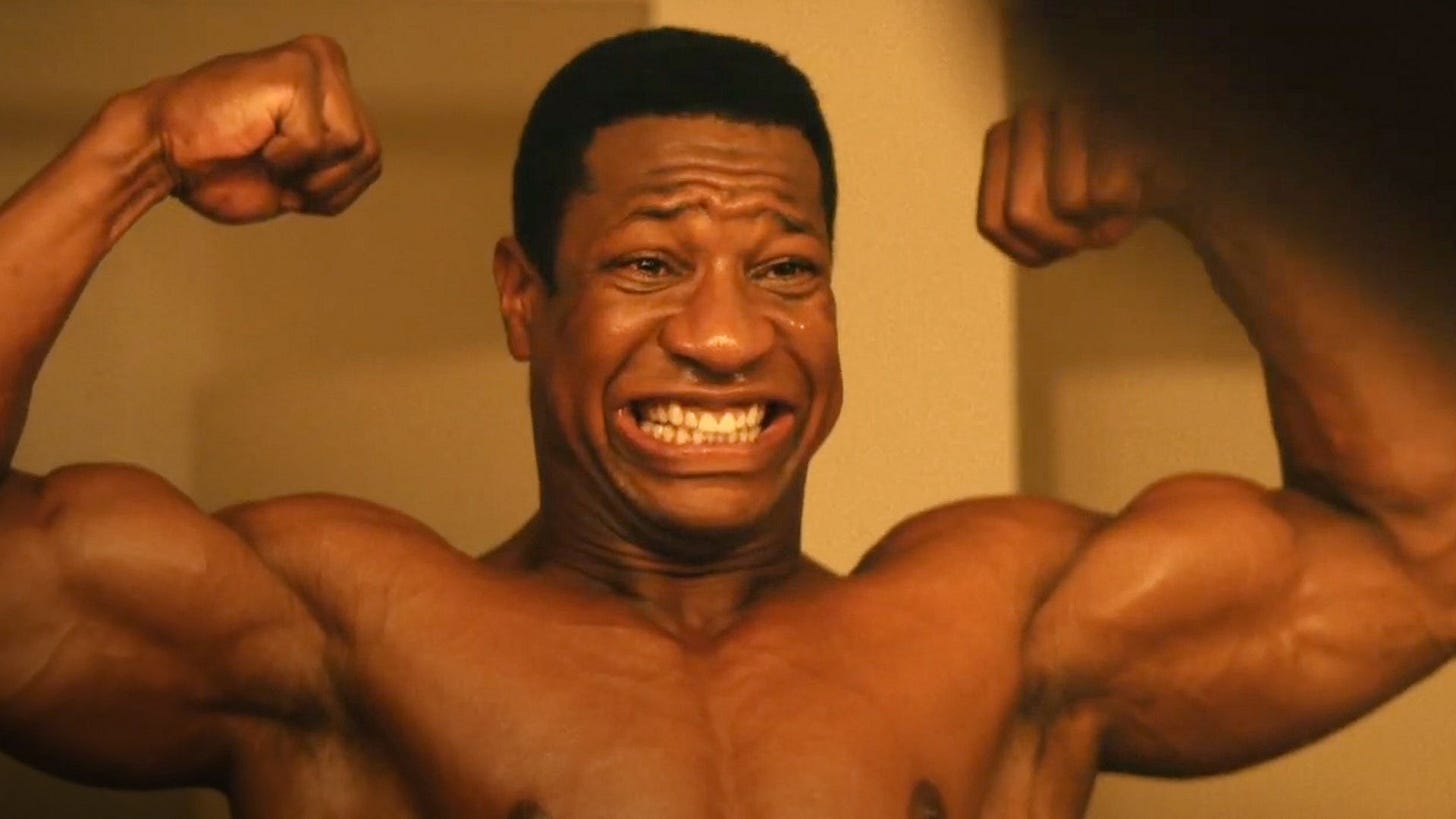

As a lot of other critics have noted, Magazine Dreams borrows pretty liberally from Martin Scorsese in both subject matter and approach and, as this is sometimes to its detriment. There's a lot of Richard Wright’s Native Son here, too, particularly in the way that Killian’s actions are in many ways foreclosed by the deeply racist society in which he lives. These elements don’t always sit neatly alongside one another, mostly because it’s kind of a slog of a film, repeatedly subjecting its hero to new and increasingly gruesome forms of violence. To his credit, Majors gives a haunting and fully embodied performance, if an uncomfortable one, even as director Elijah Byum seems to delight in the inherent grotesquerie of both the product of bodybuilding–which often pushes the male form into an exaggeration of its essential form–and also the steps that men take in order to build themselves to such a hyperbolic degree.

The longer I’ve sat with the film, the more I’ve come to appreciate the way that it plays with and teases us with the specter of queer desire, allowing us as viewers to see how yearning for the male form–either to be it or to possess it or some toxic combination of the two–can drive a man to become a monster. Killian is the type of character who is fascinating because he is so fundamentally, one might say queerly, unknowable. Just as queer desire always lurks beneath the surface of the film, never quite daring to say its name, so does Killian’s subjectivity never really gel into coherence.

Though he never quite puts it this way to himself, it’s clear that desire for the male form motivates much of Killian’s bodybuilding obsession. His walls are filled with posters of men flexing and posing, all of them paragons of masculinity, the male essence distilled into its most bulging, well-sculpted form. He spends most of his time watching old videos of bodybuilding competitions, his gaze riveted on the screen, drinking in the sight of muscled and well-oiled bodies. As other critics have noted, there’s something particularly suggestive, if vulgarly so, about the way that his energy drinks dribble out of his mouth as he gazes with such rapture at the bulging male bodies on screen. Like so many other men, Killian (and the film itself) can’t seem to decide whether he wants to have sex with the men on the screen or to be them.

And it’s not as if his relations with women are particularly good. The two times that he actually manages to have a connection with someone of the opposite sex things quickly go off of the rails. During a date with a coworker he flippantly informs her that his father killed his mother before killing himself, an admission that precedes his ordering a little of almost everything on the menu (all protein, of course). Small wonder that the woman, clearly disturbed by all of this, flees without telling him that she’s leaving. Equally awkward is his encounter with a sex worker, which ends up satisfying neither of them when he recoils from her touching him. Clearly Killian is as alienated from his own body–and arguably from his own mind, since he hasn’t really processed the trauma of watching his father kill his mother and then himself–as he is from that of others.

Then there’s the moment when Killian, having finally managed to connect with his idol Brad Vanderhorn, ends up going to bed with him, or so we’re led to assume, given that they wake up naked in the same bed the next morning. The film is frustratingly and provocatively coy about just what it is that transpired between the two men, but it’s an intimate moment that was dubious in terms of consent, as Killian himself makes clear in his later (unanswered) correspondence with his idol. For a man like Killian even sexual intimacy is bound up with notions of power and control–or the lack thereof–and he ends up as thwarted and unfulfilled by this encounter with the man he has idolized, fetishized, and stalked for most of the film.

Though it stumbles at times–and though it can never quite escape its indebtedness to other, better films–there’s still something strangely and hauntingly poignant about Magazine Dream’s portrait of broken masculinity. Killian, like so many other young men today, labors under the delusion that sculpting his body into a fortress of muscle will render him invulnerable, that becoming a muscle god will give him some form of power or social capital. When his attempts to become a champion bodybuilder don’t work out as quickly as he’d like, he tries uploading amateur videos to YouTube. Unfortunately, as he learns too quickly, attempting to find validation from the internet is a loser’s game. His attempt to gain internet fame ends in humiliation when his posing soliloquies are met with nothing but scorn and contempt from the cruel voices that make the internet their favorite haunt.

Given all of this, it’s no wonder that Killian descends ever further into violent derangement, leading to a particularly horrifying moment in which he almost kills a judge who critiqued his deltoids, an insult that clearly wormed its way into his consciousness. After forcing the man to strip and coming perilously close to shooting him, however, he ultimately decides not to do so, just as he decides not to go through with an assassination of Vanderhorn, despite the fact that doing so would perhaps mark a moment of reclamation for him. These are but two of many moments in which violence, desire, and twisted self-image combine in this film, though it’s worth noting that Killian manages to escape from the consequences of his actions remarkably adeptly. (Though it’s also worth noting that an X-Ray shows a brain that is quite damaged, with bits of metal visible. Perhaps we can think of Killian as a type of cyborg, particularly once you take his repeated injections of steroids into account).

By the time that the film reaches its conclusion, Killian has come to an important understanding. Nothing he does, whether it’s violence, sculpting his body into a tank, or lashing out at those who offend him or challenge him, is going to ever quite fill up the emptiness and the darkness inside of him. There is, I think, a measure of peace in the ending, which sees him throw out all of the accoutrements of his bodybuilding adventure and simply pose in his garage. It’s a somber yet peaceful ending to a violent and terrifying film.

Is Magazine Dreams a brilliant, or even a particularly good, film? I honestly don’t think so. It cribs too much from its sources to ever really stand on its own, and it seems to mistake its own blunt approach–and its star’s disturbingly visceral and embodied performance–for powerful cinema. Even so, I remain fascinated by the way that it plays with queer desire, exposing (unintentionally, perhaps) the way that this specter continues to haunt the male imagination.