Sinful Sunday: The Deadly Queer Murderers of "Deathtrap"

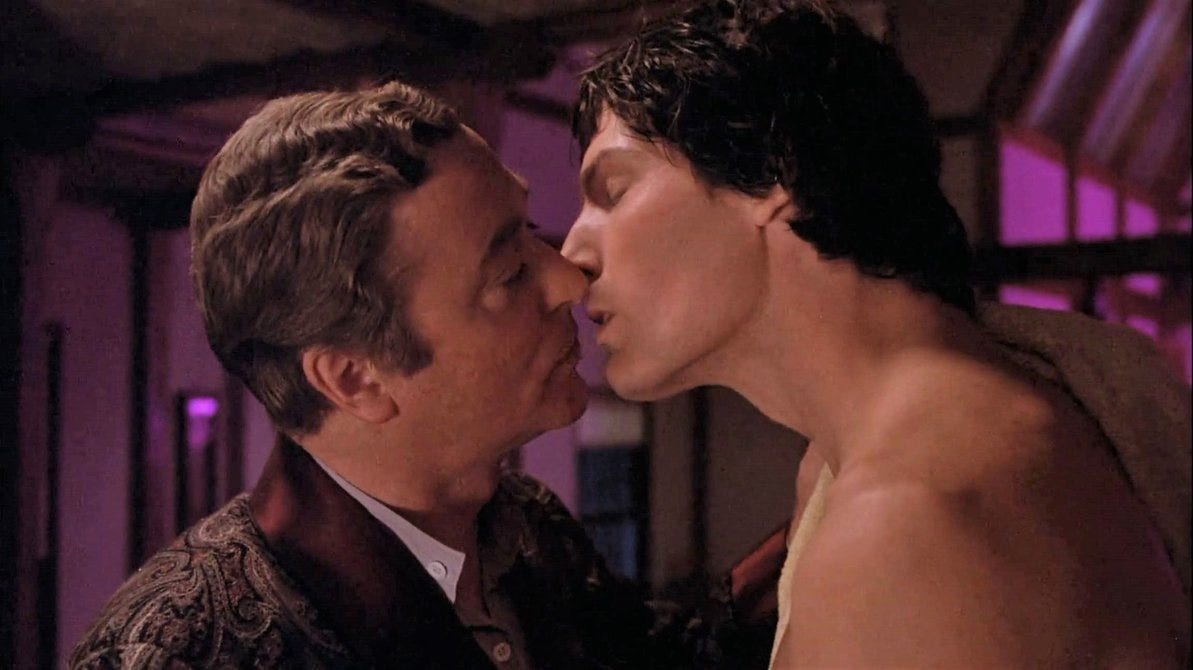

Michael Caine and Christopher Reeve deliver a pair of divinely deadly performances in this film about yet another pair of murderous mos.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Welcome to “Sinful Sundays,” where I explore and analyze some of the most notorious queer villains of film and TV (and sometimes literature, depending on my mood). These are the characters that entrance and entertain and revolt us, sometimes all three at the same time. As these queer villains show, very often it’s sweetly good to be bitterly bad.

I distinctly remember my first experience with Deathtrap, a play about a fading playwright who schemes with his male lover to murder his wife. I was in undergrad, and I was still new to this whole live theater thing, so I had literally no idea what was about to happen. Even now I can still remember the frisson of excitement that raced through me at the same-sex kiss which brings the first act to such a titillating close. I was still a fresh-faced country bumpkin new to the big college town, and seeing queer desire brought to life on-stage was still new and exciting for me.

It wasn’t until years later that I would get around to watching the film version starring Michael Caine as playwright Sidney Brul and Christopher Reeve as Clifford Anderson, his young protege, lover, and accomplice. When the film begins Sidney is devastated by the failure of his recent play, and so he sets in motion a plot with his young lover Clifford to give his wife Myra a heart attack (he will pretend to murder Clifford, and then Clifford will seemingly return from the grave and assault Sidney and chase his wife through the house). With her death, he’ll inherit her wealth, giving them both the leisure to live their lives as they see fit and to pursue their artistic ambitions. Though the plan succeeds, the two men begin to turn against one another, particularly once Clifford reveals his intent to publish a play whose plot mirrors the very murder plot they have just perpetrated. Sidney, dismayed by this turn of events and increasingly convinced that his lover is a sociopath, decides to murder him, and even more chaos ensues.

Like other killer queers in the history of Hollywood–I’m thinking in particular of the Brandon and Phillip in Rope–Sidney and Clifford are compelling precisely because they ask us as viewers to enjoy their villainy. Throughout the film we’re caught on the cusp of wanting them to get away with it, even as we’re also aware that things between the two men are not all that they seem. For all that they have clearly been lovers for a while, it’s just as clear that this has been a relationship of opportunity, at least as far as Clifford is concerned. For Sidney, on the other hand, the handsome and hunky younger man has, as he says, shown him a way of life that he had never imagined before. It’s the closest the film comes to a touching emotional scene between the two men. It’s just a shame that such a sentiment cannot last.

Caine makes for the perfect suave but fading playwright, a man convinced of both his own genius and the injustice of a public that doesn’t see him for who he truly is. There’s no question that Sidney is a duplicitous and morally bankrupt man, for all that he claims he didn’t really want to kill his wife. The fact that he is able to summon up false tears while calling the emergency services to tell them of her demise suggests that he is very good at deception, both of himself and others. Indeed it’s sometimes hard to tell just how much he believes in the pack of lies he has constructed around his life. Just as importantly, he also shows himself to be quite ruthless when necessary; aside from his plan to murder Clifford, he is quite abusive to his wife even before he brings about her demise. In addition to shouting at her every time she dares to voice opposition to his plans, he also physically drags her downstairs so he can prove to her that Clifford has not magically returned from the dead. For all of his refined mannerisms, it seems that Sidney really does have a natural soul.

For me, though, Reeve’s Clifford Anderson is the most compelling aspect of the film. Reeve’s hunky physique makes him a looming kind of threat the moment that he walks in the door, and it’s fascinating to see someone go from playing the honorable Superman to a devious and deviant young man that we are clearly meant to believe is a sociopath. There’s a feral glint in his eyes that leave us is no doubt as to just how troubled he is, and the iciness of his delivery–particularly when he informs Sidney that he will publish Deathtrap with or without him–is a reminder of Reeve’s considerable talent as an actor. This is a young man who, we are led to believe, has had more than his fair share of run-ins with the law and, as the desire to publish Deathtrap reveals, he is also someone who seems to get a peculiar thrill from flirting with danger and destruction.

As the second act unfolds and these two conspirators and lovers begin to turn against one another, their little domestic idyll slowly becomes more toxic as they find that the life they had envisioned isn’t quite what it was supposed to be. Much of their ensuing conflict stems from their widely divergent professional skills and ambitions. While Clifford truly seems to believe that Deathtrap will be a hit, Sidney can’t overcome the writer’s block that has blighted his creative impulse. Though many of their mannerisms come to resemble those of an old gay couple–bickering, back-biting and, of course, gossiping behind one another’s backs (in one bitterly ironic scene, Sidney remarks to his lawyer that he wonders if Clifford is a homosexual; he has no problem with that, he says, as long as he doesn’t come prancing into his office with his fairy wings. This is quite a bit of hypocrisy from a sad old queen like Sidney).

Ultimately Deathtrap, like so many other films before it, draws an intrinsic connection between queer desire and death. Not only do Sidney and Clifford bring about Myra’s demise, but as the play reaches its conclusion they end up murdering one another, their love doomed from its inception. While this might seem to align it with so many other negative portrayals of queer love in the movies, which almost invariably end with annihilation, the film’s own self-awareness and self-reflexivity–in a final twist, it’s revealed that the daffy psychic from next door has taken the whole strange set of events and transformed it into a blockbuster play called…Deathtrap–means that the whole thing should be taken with a grain of salt. Combined with the arch performances from both Caine and Reeve, this film reminds us that even queer characters are just creations and simulacra. They belong forever to the deathly realm of the fantastic.

I loved this movie. Thanks for bringing this up.