Sinful Sunday: "American Sports Story" and the Complexity of Queer Villainy

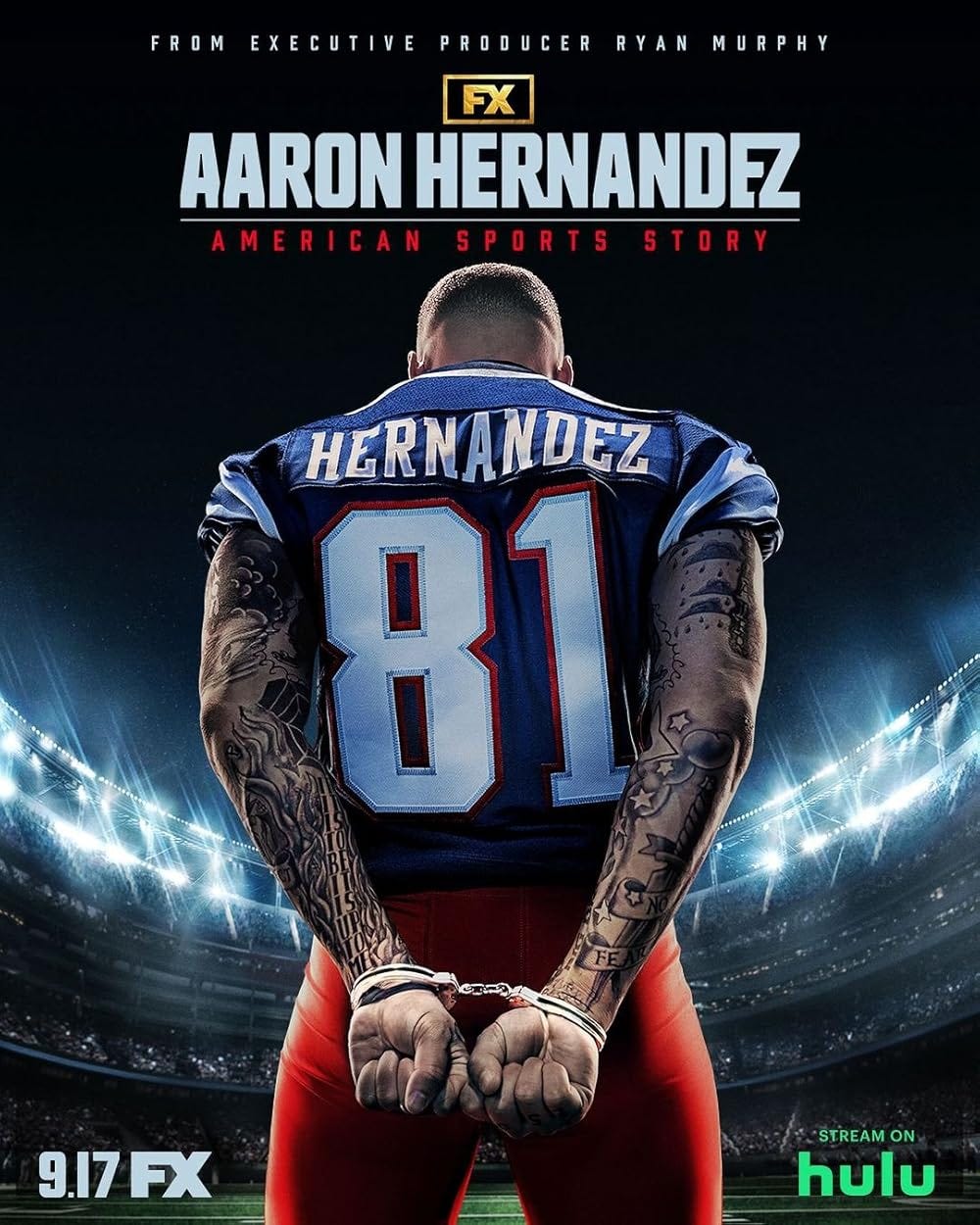

The Ryan Murphy series sheds much-needed light on the various institutions and people that failed the infamous murderer, including Aaron Hernandez himself.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Welcome to “Sinful Sundays,” where I explore and analyze some of the most notorious queer villains of film and TV (and sometimes literature, depending on my mood). These are the characters that entrance and entertain and revolt us, sometimes all three at the same time. As these queer villains show, very often it’s sweetly good to be bitterly bad.

A few weeks ago I wrote about American Sports Story: Aaron Hernandez, which focuses on the title character, (in)famous NFL player Aaron Hernandez, who was convicted of first-degree murder and ended up taking his own life while serving a prison sentence. As I noted at the time, the series is remarkably adept at showing the tragic arc of Hernandez’s story, as he goes from being a beloved football icon to a pariah, even as he also struggles with his sexuality and a perpetual sense of never being good enough, to say nothing of the damage that he is doing to his brain by continuing to play professional football.

Now, having completed the show, I have to say that I’m still impressed. This is one of Ryan Murphy’s more coherent television offerings this year, deftly showing the many troubling forces at work in Hernandez’s life, all of which acted together to push him down the path of darkness that led to murder and, eventually, suicide. While it certainly does have its sensationalist moments, for the most part it’s a much more restrained–and, I would argue, thoughtful–exploration of a very troubled and tragic queer soul.

American Sports Story succeeds in large measure because of the soulful and haunting performance from Josh Andrés Rivera, who portrays the doomed Hernandez. From the first episode to the last, he gives us a look behind the blunt facade, showing us that there is more to him than just football. One of the most astonishing things about his performance is the extent to which he can juxtapose Hernandez’s gentler soul with his hard exterior. This is a man, after all, who has forged his body into the human equivalent of a tank, both because it helps him succeed at his chosen sport and, more importantly, because it insulates him from his own fraught emotions, including his desire for other men.

It’s this skillful tension that makes the scenes showing Hernandez’s crimes so heartbreaking. The series never tries to excuse Hernandez’s actions, and it certainly doesn’t shy away from showing just how brutally violent he could be, often with little to no justification. Even so, since we as viewers know about his emotional turmoil and the physical toll that his football career has taken on him (there are repeated instances in which a blow to the head is quickly followed by ringing and a distorted sense of reality, all of which begin to add up). By the time the finale comes along, we already know what’s going to happen, as unable as Hernandez to escape the sense of tragic inevitability. There can be no escape for Aaron, both because of his own actions and because of the toll his football career has taken on his body.

One of the most persistent themes in American Sports Story is Aaron’s deeply repressed queer desires, many of which find expression in his sometimes-sexual relationship with Chris (Jake Cannavale). There’s something poignant and deeply sad about the moments in which they meet up for some steamy sex in some random hotel Though it’s clear that the two of them can never pursue a full-time relationship, one still gets the sense that engaging in same-sex eroticism allows Hernandez to feel more fully connected to his inner self in a way that is simply not possible in the life that he has constructed for himself, one in which he has responsibilities and a safely heterosexual (if deeply troubled) relationship.

Moreover, his interludes with Chris are but islands of peace in a life filled with tumult and trouble. Moreover, as Aaron himself admits to his wife late in the series, he ultimately regrets not being able to love her in the way that he should have. This is the closest he will ever come to admitting the truth about his identity, and I admit that I found myself more than a little moved. The series implicitly asks us as viewers to think about how different Hernandez’s life might have been had he ever been given the chance to live an authentic life rather than one perpetually marred and distorted the pernicious logic of homophobia, machismo, and the closet.

It’s fitting, perhaps, that the last thing Hernandez experiences before he ends up taking his own life is a drug-fueled encounter with his father, the man who has cast a shadow over his entire life. So distorting has his father’s influence been on sense of self that he ultimately can’t escape it, no matter how hard he tries. And, because he feels that he has failed to live up to the lofty expectations of the man who died when he was still a teenager, he seems to feel that the only alternative is to take his own life.

As much as American Sports Story is concerned with Hernandez’s own decisions and the steps he took that led him down the road to self-destruction, it also focuses on the other forces that shaped (and misshaped) him. Some of these are personal. His father, as I’ve already noted, attempted to beat even the faintest trace of weakness or effeminacy out of his younger son, inflicting psychological damage from which he never fully recovers. Then there’s his mother, who remains far more concerned with how everything affects her, with almost no emotional energy or support left to give her son, even when he’s on trial for murder.

Others, however, are much deeper, more structural, even if they also depend on the actions (or inactions) of those in Hernandez’s orbit. Just as university football staff refused to take him in hand or give him the discipline he needed to straighten up in his youth, so the coaching staff of the Patriots seem more than happy to turn a blind eye to him, only to swiftly cut him loose when he is a danger to their bottom line. Hernandez, like so many other professional athletes, learns to his chagrin that he is nothing more than a commodity, to be used up and then tossed aside as soon as it is easy and cheap to do so.

Ultimately, American Sports Story is a queer tragedy about a closeted man who was repeatedly failed by those who should have had his best interests at heart and by a culture and a family that couldn’t or wouldn’t see him for who he truly was. The series doesn’t excuse his actions, of course, but it does at the very least allow us to understand the context out of which he emerged.

This tragedy is made all the more wrenching by the revelation in the final episode that Aaron’s brain was irreparably and terribly damaged by his time on the field. As the doctor pronounces, within a decade he would have been almost completely incapacitated. Even had he lived, even had he been able or willing to turn his life around, there was no chance that Hernandez would ever have had anything other than a tragic life.

It’s a haunting, but fitting, conclusion.