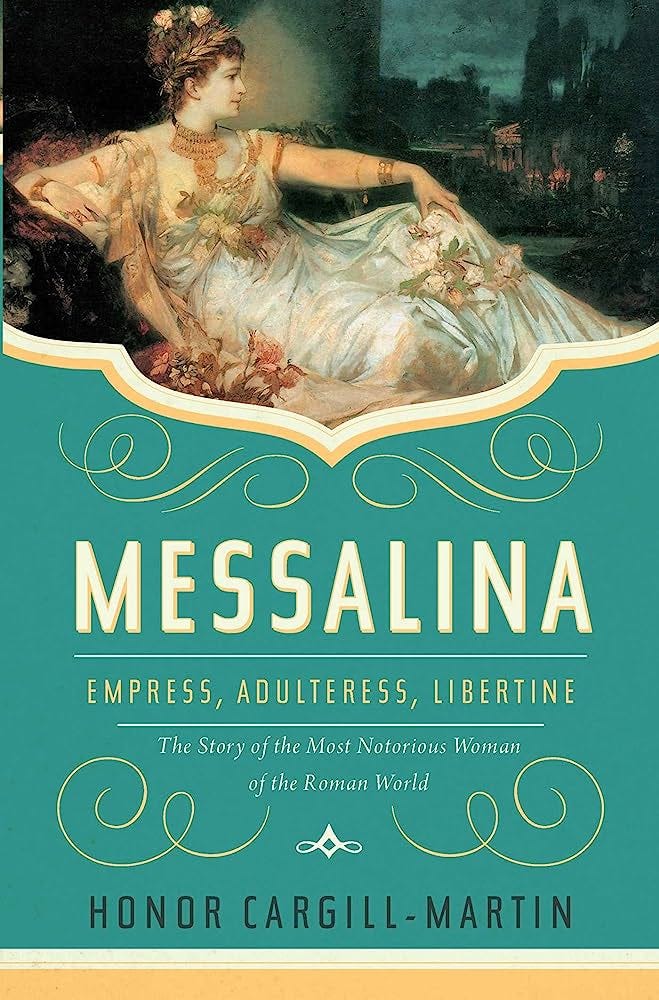

Reading History: "Messalina: Empress, Adulteress, Libertine: The Story of the Most Notorious Woman of the Roman World"

An important new biography sheds important light on the political acumen of one of the ancient world's most notorious women.

Few women in the ancient world have had as much of a scandalous reputation as Messalina, the third wife of Claudius. Renowned–and reviled–throughout history as a notorious wanton, her name has become virtually synonymous with promiscuity, a perception birthed by ancient historians such as Cassio Dio, Suetonius, and Tacitus and repeatedly reinforced throughout the millennia since. The truth, Honor Cargill-Martin argues in her erudite new biography, Messalina: Empress, Adulteress, Libertine: The Story of the Most Notorious Woman of the Roman World, is far less scandalous and far more interesting. Rather than a simple libertine who was driven by her own relentless appetites, Messalina emerges from these pages as a fierce and politically canny young woman, someone who was determined to protect her family and her own ambitions, no matter who she had to crush in order to do so.

Messalina had the bad fortune to be born into and raised among one of the most dangerous courts of the ancient world. The regime put in place by Augustus had significantly transformed how politics worked in Rome, so much so, in fact, that by the time Messalina came of age power was often wielded behind closed doors rather than in public. This gave aspiring young women like her a chance to wield more influence than ever before, even though doing so, as the empress herself would learn, was always a dangerous time with the highest possible stakes.

As Cargill-Martin points out, Messalina wasn’t nearly as one-dimensional as the ancient writers would have had us believe. The empress emerges from these pages as a canny political strategist, someone who, in the early years of her reign at Claudius’ side, was more than willing to use her influence and power to bring about the downfall of those who she perceived (rightly or wrongly) as a threat to her own dynastic ambitions. After all, as Cargill-Martin reminds us, she had two young children by her husband–Britannicus and Octavia–and it was her duty as their mother and as the empress to make sure that their lives and their political fortunes were protected. If doing so required the destruction of potential political enemies, then that was a risk that she was willing to take.

Of course, this meant that Messalina had to make some allies whose own loyalty to her would be dubious at best and detrimental at worst. As influential as Messalina was, and as skilled at wrapping Claudius tightly around her little finger, she was matched in this regard by his freedmen, one of whom ultimately played a key role in her eventual demise. While Cargill-Martin makes no excuses for Messalina’s shortcomings and oversights, she is nevertheless deeply empathetic to her subject, and she encourages us to be so, as well. Thrust into marriage while still a teenager, then pulled into the dangerous and deadly world of Caligula and his ilk, and then finally ascending to become the most powerful woman in the world, is it any wonder that some of this went to the young woman’s head?

Cargill-Martin concludes her book with a brief examination of the many afterlives of Messalina, as subsequent generations of artists, playwrights, novelists, and sculptors have sought to use her image for their own purposes. French Revolutionaries painted Marie Antoinette as the new Messalina, as did the English opponents of the Catholic Henrietta Maria. Sculptors and painters used her image and her reported escapades to titillate their audiences in marble and on canvas. And, in the 20th century, she received a more sympathetic (though hardly laudatory) depiction in Robert Graves’ novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God and His Wife Messalina, as well as the BBC adaptation of said novels.

One of the things I most appreciated about this book was the extent to which it contextualized Messalina, and we learn not only about the details of her own life but also the world of which she was a part. Cargill-Martin situates Messalina against the Roman imperial women who had preceded her, particularly Livia, who was arguably the most successful in striking the balance between being a power-broker in private but maintaining the image of a virtuous Roman matron in public. While Messalina might not have ever achieved that balance herself, she nevertheless showed a shrewd and keen understanding of the workings of power on the Palatine, and it’s to her credit that she was able to survive as long as she did, considering how easy it was to fall from grace in the Julio-Claudian family.

Also useful is Cargill-Martin’s comparison of the legacies of Messalina and her successor, Agrippina, who would go on to have her own very eventful career at the pinnacle of Roman power. While Messalina was condemned for being too womanly–irrational, desiring, lustful–Agrippina’s failing, both in the eyes of the ancients and for many moderns, was the opposite. She was far too willing to take on the trappings of male power, which meant she condemned for exactly the opposite reasons as Messalina. Paradoxically, the fact that she was able to intervene so much in the realm of politics at least earned her the grudging respect of the ancient historians, while Messalina’s supposedly excessive femininity rendered her into an object of fear and derision, as men like Tactius used her to show the inherent corruption in the imperial form of government.

Messalina, like so many women from antiquity, has been the victim of hostile Roman sources. One need look no further than the satirist Juvenal, who seemed to take unseemly pleasure in painting Messalina as the worst sort of harlot imaginable–to see how this played out. Even Pliny got in on the act, and he’s the source of the anecdote that claims she once challenged a prostitute to an all-night sex marathon. Fortunately Cargill-Martin has no time for such patently false stories, and she wastes no time in dismissing them as the misogynist fantasies that they so clearly are. It’s truly a pleasure to watch Cargill-Martin engage with the ancient authors and peel away the layers to reveal at least some measure of the truth beneath. While we can never be entirely sure of the truth of Messalina’s life we can, as this book demonstrates, at least gain a more nuanced understanding than the ancients allow.