Queering Genesis in Eliot Schrefer's "The Darkness Outside Us" and "The Brightness Between Us"

The queer sci-fi YA duology offers an optimistic revision of the story offered by Genesis, presenting a future in which humanity might yet be redeemed.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Some months ago, one of my book clubs read Eliot Schrefer’s The Darkness Outside Us. I was immediately captivated by the book, which is a compelling and deeply poignant blend of science fiction, YA, and queer love story. Along with its sequel, it explores the lives and loves of Kodiak and Ambrose, two young astronauts who are dispatched into space to journey to a distant planet to rescue the latter’s sister. As they discover, however, this is a lie, and they are instead one of a series of clones who will keep the ship running until it reaches a distant planet. However, they rebel against the tyranny of the operating system and, at novel’s end, they are on a new planet. When The Brightness Between Us begins, the two of them have been on the planet for quite some time and, thanks to the presence of the embryos stored in the ship, have started humanity anew with two children, Owl and Yarrow.

This is all heavy stuff, and the two novels deal with all sorts of heavy philosophical and moral questions, particularly surrounding individual agency, humanity’s perpetual desire to destroy itself, and whether the species is worthy of salvation. At the same time, the duology also uses the narrative patterns of the Book of Genesis–in combination with a touching, poignant, and powerful queer love story–to offer a more optimistic and hopeful look at humanity’s future beyond the bounds of Earth and its troubled, blood-drenched history.

The echoes of Genesis in The Darkness Outside Us are there almost from the beginning, when it’s made clear that both Kodiak and Ambrose are being held in a deliberate and stifling state of ignorance (or innocence, depending on your point of view). As in Genesis, knowledge is that which is forbidden to them for reasons that they can’t fathom, and only gradually does it become clear that they have been duped into this mission. Once they realize that they are but one set of clones and that they are essentially cannon-fodder to ensure that the spaceship and the embryos on-board make it to a new planet, however, they soon begin to rebel against the godlike artificial intelligence that runs the ship.

Particularly jarring and visceral is the moment when Ambrose and Kodiak end up killing most of the clones who are still in stasis. I don’t think it’s pushing things too far to suggest that in this we see an uncanny echo of the story of Cain and Abel. Paradoxically, in murdering their clones Kodiak and Ambrose are, unlike Cain, setting themselves free and putting them into a position of power within the ship rather than earning themselves punishment. In making sure that they are indispensable, they guarantee their future and that of the humanity they will lead.

As will occur throughout these books, it’s the queer relationship between Ambrose and Kodiak that allows each of them to rewrite the collective story of humanity. Whereas in Genesis Adam and Eve are cast out of the Garden for daring to violate God’s command for them not to eat of the Tree of Knowledge, and while Cain is marked forever by his murdering of his brother, these two queer lovers have forged an extraordinary bond that nothing can break. Once they overcome their initial antipathy–they come from two different superpowers on Earth, each of which loathes the other–their love flourishes. Indeed, it is precisely their romantic bond that not only enables them to survive a ship designed and determined to kill them but also paves the way for their settlement of the distant planet to which they have been sent.

When we rejoin them in The Brightness Between Us, it’s impossible not to feel a flush of joy at seeing these two men in the midst of their new Eden. For a time it almost seems as if they have really succeeded where, by all rights, they should have failed. Their new Eden is, to be sure, a difficult planet and there have been some struggles when it comes to getting the embryos to come to term, but they have nevertheless eked out some success.

Yet, just as the Garden of Eden was betrayed from within, not all is well within this new family. Yarrow, the boy, seems at first to be fairly normal but, unbeknownst to all of them, a rabble-rouser and revolutionary from Earth’s past managed to implant the embryo with a mutation that leads to violence. The hope, of course, is that this new idyll, much like its biblical counterpart, will be destroyed from within, the new humanity murdered in its cradle so that it can’t grow into the fullness of its powers. Like the serpent in the Garden, he comes dangerously close to bringing this entire project crashing down–he even manages to seriously wound Ambrose–but thankfully The Brightness Between Us is a much more optimistic work than Genesis. As the novel draws to a close, the four of them have gone underground in the hopes that they can weather a comet strike, while Yarrow is poised to be rescued from his deeply-bred violent impulses thanks to a broadcast from Earth’s past.

The salvation of the present and the future occurs thanks to the actions of Kodiak and Ambrose of the past, who had the foresight to send forward knowledge that would help their progenitors undo the damage to the embryos’ DNA. Knowledge, once again, becomes an agent of social power and positive change rather than some disruptor of a primordial innocence. Moreover, it's a specifically queer sort of knowledge, since the former versions of the characters, much like their descendants, end up falling in love, right before the world is essentially brought to an end by a nuclear conflagration. In their end, paradoxically, there is a new beginning for humanity as a whole.

In these two queer sci-fi books Eliot Schrefer has given us a remarkable reimagination of the story of Genesis. Rather than one of humanity’s fall because of its own corruption, however, this duology instead suggests that, through a queer relationship and its progeny, the human race might indeed be able to begin again, might indeed be able to build a future that isn’t as benighted prone to hubris as past which gave birth to it. While it’s always possible that the same process that led humanity to destroy itself on Earth might yet repeat itself again, there is far more reason for hope. As this new family hovers in their underground bunker–itself a seeming allusion to Noah and the Ark and the waiting out of the world-ending-flood–hope springs eternal. The comet might scorch the planet’s surface, the novel suggests, but in doing so it might pave the way for a new beginning.

Queer love and desire, then, are nothing short of life-giving and life-affirming, taking the Genesis narrative and turning it from one of tragedy and the inevitability of humanity’s fall into collective mortality and death into one of joy, found family, and hope for the future.

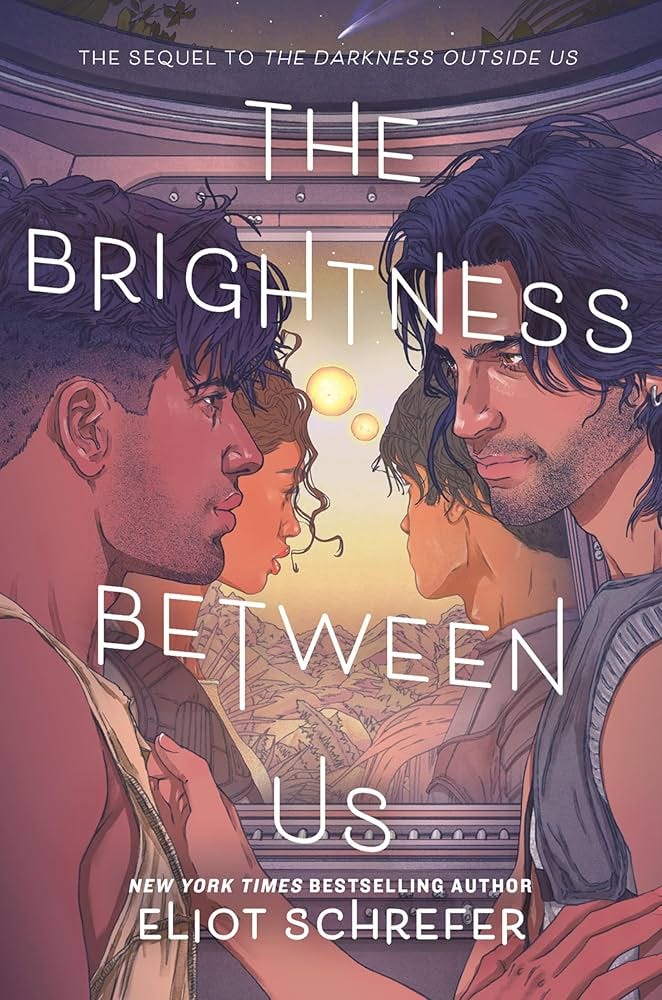

![The Darkness Outside Us [Book] The Darkness Outside Us [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CvzM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff4b89a95-c9e4-4f50-b98c-586c0624edee_1600x2408.jpeg)

I devoured this duology! So compelling, and such a delightful surprise, because it definitely rose WAY above its marketing in terms of depth and message. Fantastic storytelling!