John Wick and the Enduring Power of Male Melodrama

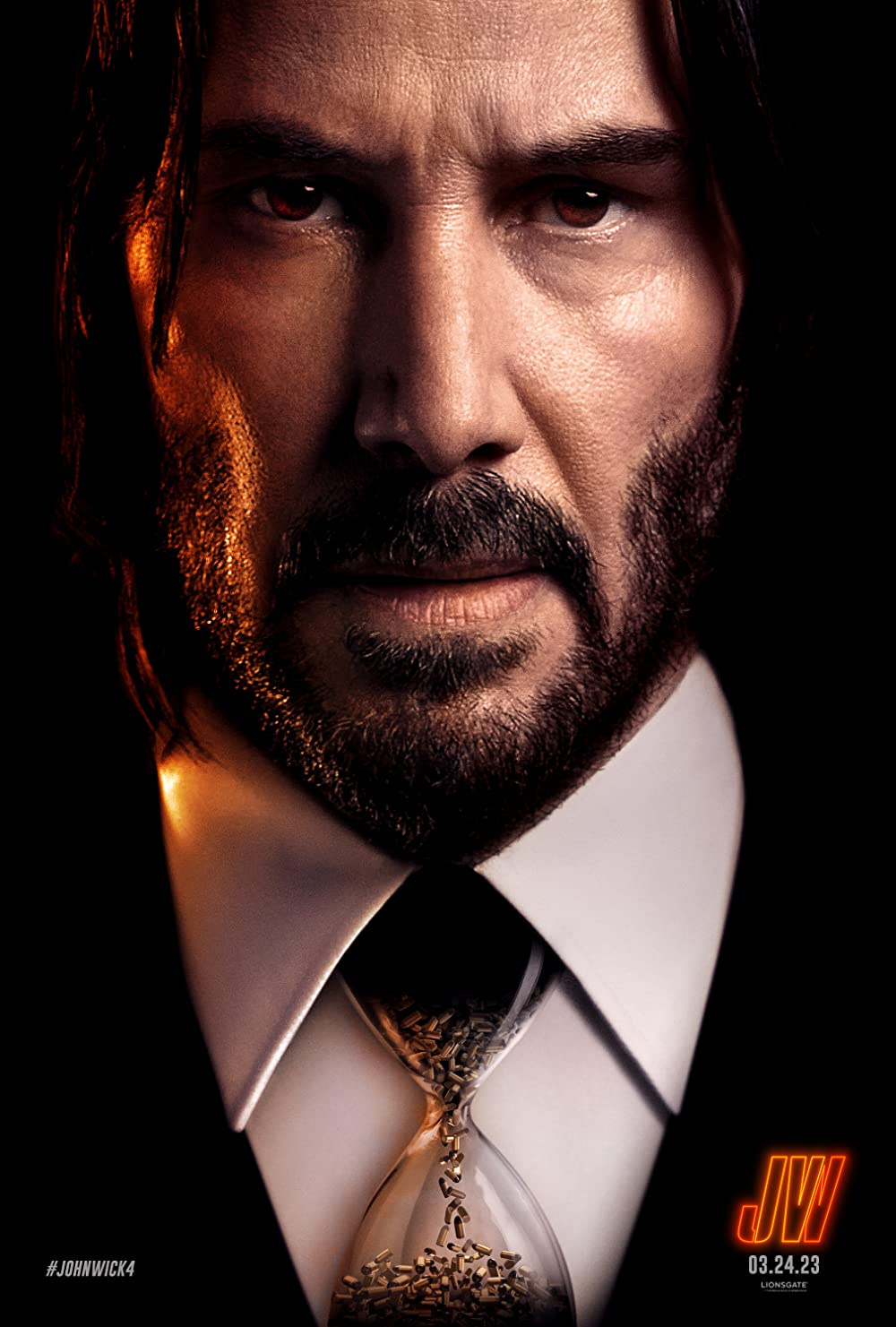

With each installment, the popular franchise starring Keanu Reeves heightens the emotional, and moral, stakes of its antihero's journey.

I seem to be one of the last people on the planet to have started watching John Wick. I didn’t avoid it for any particular reason, really. After all, I love action movies as much as the next person, and I’m particularly fascinated by the way the genre serves a similar emotional function for men as romantic comedies and romances and maternal melodramas do for women. And, of course, I’m also fascinated by Keanu Reeves, whose star text has become ever richer and more complex with each passing decade of his career and whose popularity has also continued to grow. Given all of the hoopla surrounding the most recent (and perhaps final) installment, John Wick: Chapter 4, I decided that it was finally time for me to hop on the bandwagon, and so I started with the first film and worked my way through the sequels.

With each subsequent chapter, something became increasingly clear to me: I was watching male melodrama distilled into its purest form. By melodrama, I don’t mean the pejorative that far too many film critics continue to use to dismiss those films they deem to be too emotional or excessive (or, at least, I don’t just mean that, though each subsequent film in the franchise has become more excessive in almost every detail). No, instead, I have something very particular in mind, namely the way that melodrama is used within academic film criticism to denote a mode–or a sensibility–within American culture that renders complex moral questions morally explicable through an attention to powerful emotion.

Specifically, I want to draw attention to Linda Williams who has, I think, written one of the best books about melodrama, Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson. Among other things, she argues that melodrama begins, and wants to end, in a space of innocence. Moreover, she argues, melodrama is by and large a conservative mode of visual expression, and so it is very often “moves to restore some semblance of a lost past” (36). And, because melodrama often relies on a temporal structure of too late/in the knick of time, it also constantly invites the viewer to vacillate between both action and pathos.

From the first moments of the first film in the John Wick franchise, it’s evident how invested it is in creating a space of innocence for its title character, only to repeatedly (one might even say ruthlessly) tear it away from him again and again. When the film opens, Wick is a former assassin who, after his wife’s death, tries to regain the sense of peace and meaning that she brought to it. His wife, clearly anticipating this struggle, has a puppy delivered and, in their relatively few scenes together, it’s clear how much joy this little bundle of joy brings to Wick: cuddling up with him in bed, begging for walks, just generally being a really, really cute puppy.

Unfortunately for them both ,all of this comes crashing down into blood and ruin when the son of a Russian gangster breaks into Wick’s house, has his goons beat him up and, for good measure, kills said puppy. Wick then reveals just how ruthless and relentless he can be, as he tracks down and destroys those who were responsible, each brutal death paradoxically moving him both further away from and closer to the space of innocence with which the film began. Having accomplished his task, Wick watches a video of Helen who, from beyond the grave, enjoins him to return home. He does so, a newly adopted pit bull in tow. Innocence, at least a form of it, has seemingly been restored.

In the second film, However, even Wick’s home–the one place in the world that symbolizes his innocence and the life he once shared with Helen–is taken from him when an ambitious Italian criminal, having failed in his efforts to get Wick to assassinate his sister, burns the house to the ground. The camera dwells with particular attention to the sight of a photo of Helen crumpling up as the flames consume it and it’s clear that, for Wick, this destruction has particular significance. It is, ultimately, the one last thing that he had linking him to the past and the redemption he found in his wife’s arms. Without it, he becomes a true angel of death but, for all of the agency he seems to have, in truth he is once again a pawn in the hands of others. By the time the film has come to its conclusion he has managed to kill the man who destroyed his home, but in doing so he has rendered himself “excommunicado,” so that every hand in the criminal underworld is turned against him.

The sentence of “excommunicado” carries over into the third film, as Wick tries to evade the hordes of assassins who have set out to kill him, while also seeking out the Elder, who wields power even over the High Table. Throughout the film, it’s made clear and again that, when it comes down to it, the only thing Wick wants more than anything else is to be able to leave the world of ugliness, violence, and killing to which he has been sentenced and to return to simply mourning his wife. Yet, in true melodramatic fashion, this is the one thing that he can’t do, both because his own actions precipitate the conditions of his further alienation from the idealized space of innocence and because the underworld–particularly the High Table–refuses to relinquish him. Even more wrenchingly, he is even forced to give up his wedding ring–the literal physical manifestation of his enduring bond with Helen’s memory–to the Elder, who also demands that Wick remain loyal to the demands of the High Table. Twists and turns abound in this installment and, when Winston offers him another chance in which to escape, he takes it, only to find himself betrayed yet again, wounded and left for dead.

And so, at last, we come to John Wick: Chapter 4, which elevates the melodrama, the action, and the violence to a form of popular pulpy art. Having survived Winston’s shooting of him at the end of Parabellum, John Wick returns, even more intent on destroying the High Table than ever. His opposite number is the Marquis Vincent de Gramont, played with melodramatic flair by Bill Bill Skarsgård. The film’s almost 3-hour runtime is filled with the same kinetic pleasures that we’ve grown used to in the prior three installments, buttressed by a pulsing soundtrack that heightens the melodrama in every way. Even during the film’s dizzying heights of brutal beauty, however, there is always the specter of loss, as we seem to know, along with John Wick, that there is only one way off of this careening train that his life has become: death. Wick is, like many a western hero, a dead man walking, as he makes clear when he speaks with Winston about what he would like to be on his tombstone, the simple phrase: “Loving husband.”

Since this is melodrama, Wick does succeed in killing the Marquis, who is brought down by his own hubris and dishonestly; say what you will about John Wick he is, at heart, an honest man, if also a ruthless killer. To heighten the melodramatic stakes even further, one of Wick’s last visions before collapsing on the steps of the church is of his wife. The religious imagery is, arguably, a bit too on the nose, but this is to be expected when one is dealing with the moral certainties of this particular mode of filmmaking. It helps that we in the audience know that Wick’s killing of the Marquis will almost certainly destabilize the High Table; having been victimized by this organization for the entire series (we’re repeatedly given scenes in which the machinery of the underworld kicks into gear to ensure that Wick is destroyed), this too seems entirely fitting.

There is also something appropriate, and emotionally satisfying, about the final scene of the film, which sees John at peace at last, buried alongside his wife, with Winston and the Bowery King looking on. Just as Helen’s tombstone bears the simple epitaph, “Loving Wife,” so John’s reads, as he requested, “Loving Husband.” Despite the enormous influence John Wick has had over the lives and influence of the High Table, and despite the mountain of bodies he has left in his wake, in the end he has become what he sought to be from the moment Helen came into his life: a husband. It is his tragic fate that he can only truly inhabit this role in death. As so often happens in the moral world of the melodramatic imagination, the space of innocence can only be attained, or represented, when the hero(ine) is no longer around to enjoy it.

Of course, it’s not just the space of innocence–and its constant deferral–which allows us to see the melodramatic imagination at work in the John Wick franchise. There is also Wick’s body itself which, as with so many other suffering heroes of action melodrama, endures a significant amount of torment. For, as much as he is willing and able to deal out death to anyone who crosses his path–whether it’s a random assassin on the street or one of the most powerful members of the High Table– his body bears the brunt of his (anti)heroic efforts. Time and again, we see him stabbed, shot, brutally beaten and, in the final installment, briefly hanged. However, our knowledge of the fact that he is enduring all of this as part of an effort to free himself of the clutches of a vast criminal underworld imbues his suffering with exactly the moral power so common in melodrama.

Moreover, it is also always/already too late for Wick to ever regain the past that he’s lost. There’s actually something quite brilliant about the way that each installment of the series moves both closer to his inevitable demise (for how can a man like Wick, who seems made for little else other than death, possibly have a place in either the regular world or the underworld of the High Table?), even as it also encourages us to want to see that demise deferred. We want John Wick to survive whatever comes at him, even as we know, on some level, that there can be no space for him, even if, as seems likely, his actions will bring about the ruin of the High Table and its corruption. Like so many other doomed male heroes of the cinema, Wick’s

So what does it mean–or more bluntly, why does it matter–that we see John Wick through the lens provided by melodrama? To begin with, it grants a more nuanced understanding of Wick as a sort of cultural avatar, one which expresses and embodies so many of the contradictions and anxieties circulating about the status of masculine and male heroism. For another, it helps to explain why the franchise has grown ever more popular with each new installment; if there’s one thing that melodrama has always done well, it’s appeal to the masses.

Now, of course, there is always the possibility that Wick will come back for yet another installment of killing and mayhem (particularly given the enormous amount of money this latest installment has already made at the box office). That possibility notwithstanding, the ending of this fourth installment is a fitting conclusion to a series that has struggled so mightily with the question of heroism in an era in which so many of the grand narratives of the past have come under increasing strain. From relatively humble beginnings as a tightly-constructed action revenge film, the franchise has slowly expanded to become a sprawling and almost operatic rumination on the nature of loneliness, masculinity, and violence in the 21st century. Even if Wick is well and truly dead, his influence on our collective imagination will surely live on.