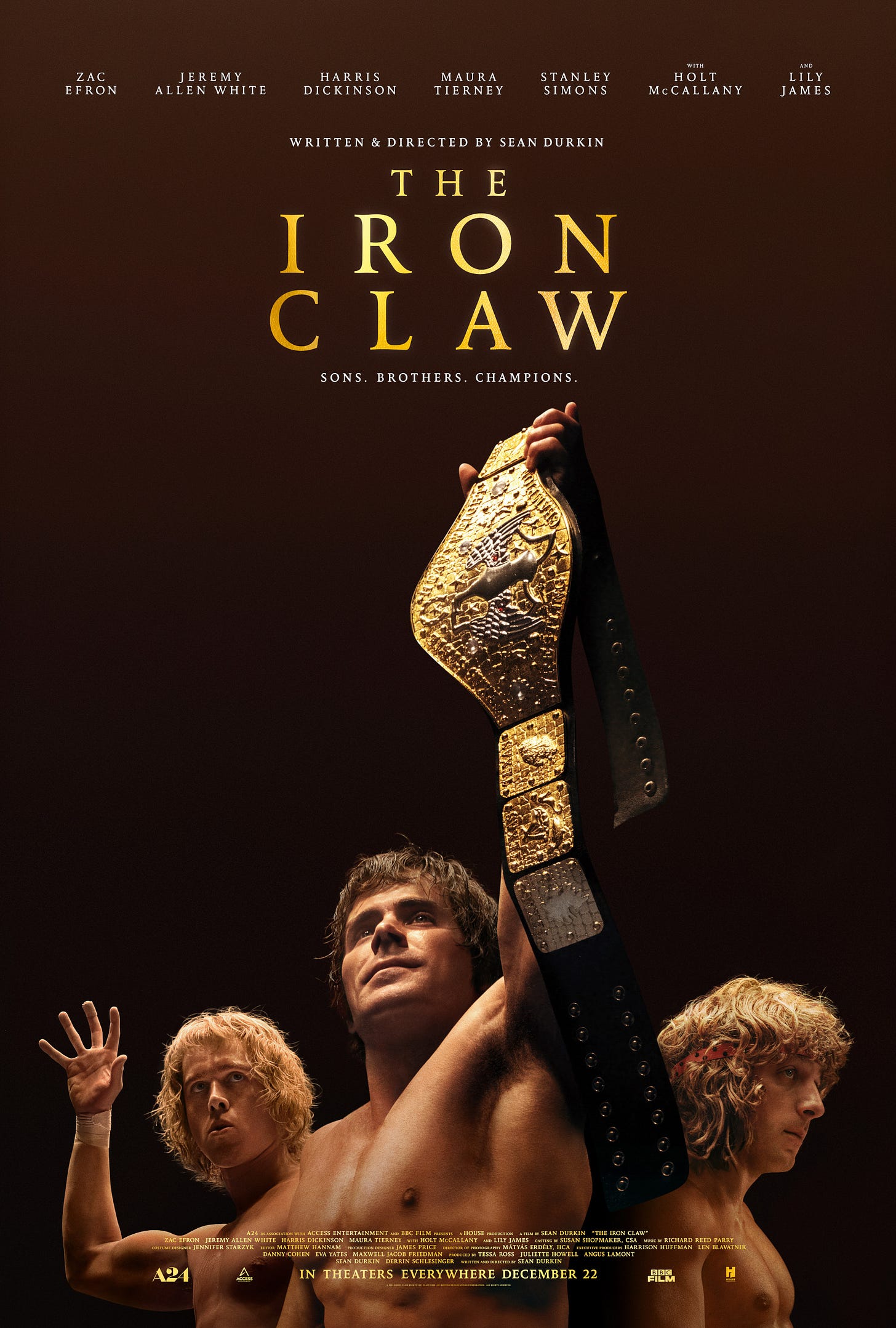

Film Review: "The Iron Claw"

The new film about the (in)famous Von Erich wrestling dynasty is part film melodrama and part Shakespearean tragedy.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

As a general rule I’m not the biggest fan of sports movies. Perhaps it’s the way that the genre so often valorizes all of the most toxic elements of masculinity, or maybe it’s because it taps into my just general dislike of sports culture and all its excesses. Every so often, however, one comes along that manages to captivate me, drawing me into the world and psychologies, and tumults of its characters. The Iron Claw is, to my great surprise, one such film.

Part of its appeal, I suspect, stems from Zac Efron, who plays Kevin Von Erich, the eldest brother in a family of professional wrestlers. When the film begins he is the apple of his father Fritz’s (Holt McCallany) eye, but he son finds himself displaced, first by younger brother David (Harris Dickinson) and then, after his untimely death, by Kerry (Jeremy Allen White) and then, after yet another mishap, by youngest brother Mike (Stanley Simons). In the end, however, it’s Kevin who is left as the last man standing and, though he manages to forge his own form of family with his wife and two sons, it’s clear the trauma of his time in the ring and the death of his brothers will haunt him for the rest of his life.

“The Iron Claw,” the Von Erichs’ signature move, comes to be much more than just a coup de grâce during a match; it’s also a metaphor for the control that Fritz wields over his sons. Though he has moments in which he shows genuine affection to his boys, he makes it clear that his love is always contingent on their performance. In one extraordinary scene early in the film, he reminds them at the breakfast table that the only way they can gain his love is by doing well in the ring–or, in Kerry’s case, at an Olympic sport–and that that love is never guaranteed or stable and that it’s always possible to move up and down the rankings.

Yet, like so many other fathers in American tragic melodramas–watching the film I couldn’t help but be reminded of Vincente Minnelli’s Home from the Hill–Fritz soon learns that his efforts to sculpt his sons into his own preferred masculine image is very much a double-edged sword. McCallany is perfectly cast as this square-jawed and paunch-gutted paterfamilias, a man so bitter about his own shortcomings in the ring that he’s willing to pummel his sons into submission, no matter the cost. This is the kind of man who fetishizes guns and forbids his sons from weeping, even when one of them dies unexpectedly, and he’s the type of man who will then push them back into the ring, no matter the risks. He’s a brute, and he shows no compunction about being so.

Much of the critical conversation around the film has centered on Efron's performance, and rightly so. He commands the camera, often seeming to bulge out of the frame but, while his body may be something of a caricature–one might even go so far as to say a travesty–of muscle-bound masculinity, there’s a haunted and yearning look in his eyes that never quite goes away. It’s there when he tries to impress his unpleasable father, and it’s there when he finally begins a relationship with Pam (Lily James), the woman who finally becomes his wife. No matter how big his body gets, it’s never quite enough to protect him from the cruelty of his father or the unforgiving nature of the ring.

Indeed, the body becomes the locus for the masculinity crisis that is the centerpiece of the film. For all of his bluff and imposing physicality, Efron’s Kevin is still just a little boy yearning for some form of stability and love in his life, and the same is true of each of his brothers, particularly Kerry. When the latter’s Olympics dreams are dashed due to the US’s boycott, he goes into the ring, but his body is as much a source of vulnerability as strength, as he finds out after a devastating motorcycle accident that leads to him losing a foot. His amputation begins a downward spiral that leads to his own suicide. Like his costar Efron, White is superbly cast, his haunting blue eyes expressing a world of hurt, desperation and, ultimately, despair.

It’s really quite striking (and disturbing) the extent to which the bodies of the Von Erichs are both their greatest strength and their most fatal weakness. Each of them endures physical torment as they try to mold their physiques into the requisite shape to be stars of the ring, but such perfectionism comes with a price. Not only does Kerry commit suicide; David ends up dying from a ruptured intestine while in Japan and Mike takes his life after awakening from an injury-induced coma, an accident that strips away his beloved musical talent. By the time that the film ends, Kevin is the only one of his siblings still alive, a weight that is as crushing as his independence from his father is freeing. Given how close the brothers were throughout their lives, we come to feel for Kevin as he bears the heavy burden of his grief and thwarted expectations.

Visually, The Iron Claw is often quite striking, particularly when it comes to the Von Erichs’ home. An early sequence of shots emphasizes both Fritz’s gun collection and the religious iconography hanging on the wall, and this is a motif that recurs, demonstrating the extent to which phallic masculinity and restrictive Christianity govern the Von Erich parents (Maura Tierney’s performance as the boys’ mother, Doris, is a small one compared to that of her husband sons, it’s nevertheless quietly devastating in its own way). Ultimately the house is alone but for Fritz and Doris, the latter of whom finally takes up her old love of painting, much to her husband’s bemusement. In the ashes of a life, what else is there to do?

There’s something almost Shakespearean about The Iron Claw. Hovering in the background of the family melodrama there is the specter of a mysterious curse, a phenomenon Kevin firmly believes in and which leads him to give his son his given last name, thus hopefully avoiding the affliction that seems to strike the Von Erichs. This being Hollywood, there’s at least a glimmer of a happy ending, and the last shot of the film is of Kevin playing football with his wife and sons and dog, a beautiful little image of a happy family that has emerged from the carnage and destruction. Given how much he has endured, however, it can only ever be a bittersweet ending. Fame has its price, and Kevin, who only ever wanted to please his unforgiving father, has been the one to pay it.

Affecting, tragic, and sometimes comedically melodramatic, The Iron Claw is a powerful reminder of the price of toxic masculinity.