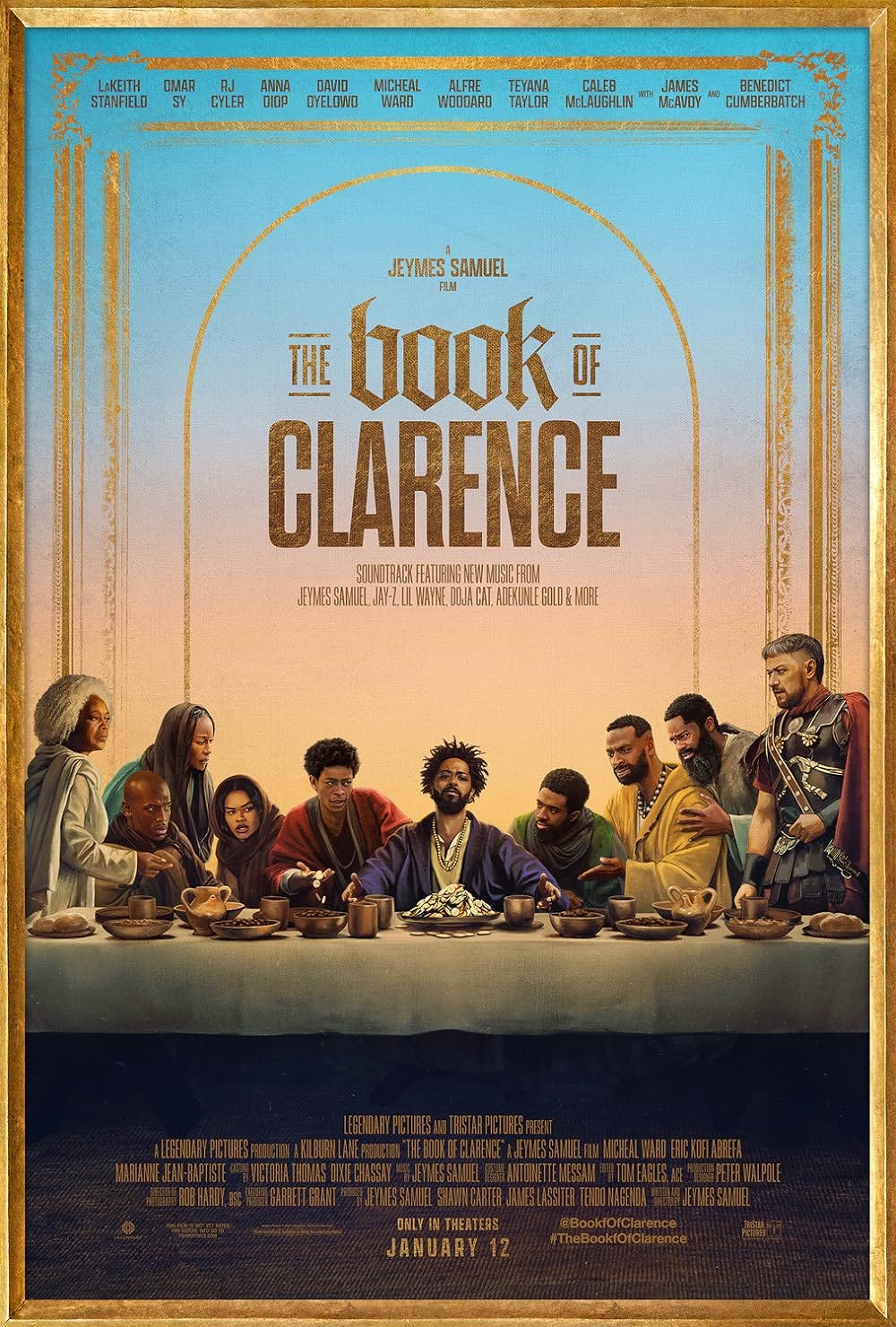

Film Review: "The Book of Clarence"

Jeymes Samuel's iconoclastic take on the biblical epics of yore subverts the genre's narrative beats and visual style, even as its central message is surprisingly devout and sincere.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Spoilers ahead!

At first, I wasn’t sure what to make of The Book of Clarence, the new film from Jeymes Samuel. The trailers made it look as if it was going to be a spoof of biblical epics a la Life of Brian and, while there are certainly some elements of the Monty Python troupe’s tongue-in-cheek approach to one of Hollywood’s most staid and devout genres, it ends up being quite a bit more somber in tone, particularly once it reaches its third act. Like many other critics, I don’t think everything about the film is as coherent as it could be but, the longer I sat with it, the more brilliant I found it.

The film primarily centers on Lakeith Stanfield’s Clarence, the twin brother of the Apostle Thomas, whose beliefs he cannot quite fathom. Indeed, Clarence is a cynic through and through, who not only doesn’t believe in Jesus and his miracles; he doesn’t believe in God at all. Something of a troublemaker, he falls afoul of noted gangster Jedediah the Terrible (Eric Kofi-Abrefa), even as he also carries a torch for his sister, Varinia (Anna Diop). Desperate for cash, he starts performing miracles in imitation of Jesus but, after he starts making money hand-over-fist, Clarence starts to feel the pangs of conscience and, rather than using his ill-gotten gains to pay off his major debts, he uses it to free a group of enslaved gladiators. Things take an even more terrible turn once he falls afoul of Rome, leading to his crucifixion and subsequent resurrection at Christ’s hands.

The film is replete with references to other biblical epics, particularly those from the genre's heyday of the 1950s and early 1960s. The chariot race with which it begins, for example, is a nice little homage to both Ben-Hur and The Fall of the Roman Empire, and his competitor Mary Magdalene (Teyana Taylor) is just as determined to defeat him as Messala is Judah or Commodus is Livius. Likewise, for about half of the film we don’t see Christ’s face, once again very much in the Ben-Hur tradition. And you can’t miss the reference to Spartacus when Clarence and his best friend Elijah (RJ Cyler) visit a gladiator school, where the former engages in a nearly deadly hand-to-hand duel with the “immortal” Barabbas (Omar Sy).

In each case, however, Samuel skillfully subverts our expectations. The chariot race ends not with the salvation of Clarence’s masculinity or his recognition of the futility of violence; instead, it ends with him sprawled in the dust and robbed of his robe. The Spartacus homage, likewise, offers a twist on its source material; rather than ending up dead and rendered into a warning spectacle–as happens to Draba in Stanley Kubrick’s film–Barabbas instead becomes a devoted acolyte and ally to Clarence. With his Achilles-like strength, he even manages to survive taking several spears in the back and in his heel (though not, fortunately, he weak one). What’s more, Samuel does all of this with a remarkable visual aplomb, and his 1st century Jerusalem is a marvel of gritty beauty.

As Barbbas’ parting cry of “wrong heel, motherfucker!” reveals, there is a lot of humor in The Book of Clarence, but it’s usually of the sort that makes you chuckle wryly rather than guffaw. It’s there when Clarence’s mother, Amina (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) gently reproves him for his night-time masturbatory activities, and it’s also there when he has a fraught conversation with Jesus’ parents wherein Clarence tries to learn the inside secrets of his miracles. Alfre Woodward is an inspired bit of casting as the Virgin Mary, exuding just the right mix of worldly wisdom and transcendent otherworldliness. David Oyelowo, likewise, is brilliantly cast as the sharp-tongued John the Baptist, who chastises Clarence for his cynicism and comes very close to drowning him in the Jordan.

Yet there is a genuine heart to this film and, like the biblical epics of yore, it is very much a story about one man’s journey from cynicism to profound faith. When Pontius Pilate, played by James McAvoy, threatens Clarence with death if he won’t betray Christ’s whereabouts, he does the noble thing and accepts his fate. Having started out as a fake Messiah, it seems that Clarence has learned a thing or two during his masquerade. There’s a soulfulness to Stanfield’s performance that, I think, allows him to sell Clarence’s conversion in a way that the screenplay itself doesn’t quite succeed in doing. Beneath all of his hauteur there is a very sensitive and bruised heart, someone haunted by the unremitting violence of the world in which he loves–the oppressive agents of the White Roman state are never far away–and by his inability to attain any form of social mobility.

The film’s tonal inconsistency can be a bit jarring and difficult to get used to at times, particularly once we get to the moment when Clarence begins his weary, bloody trudge to Golgotha. When his mother cries out “They always take our babies,” her voice a wracked sob of agony, it’s impossible not to weep, not just for Clarence but also for all of the Black men who have been brutalized in our own troubled world. Likewise, his time on the cross is excruciating to watch even, as the same time, the gravitas of the moment is somewhat undermined by the presence of Benedict Cumberbatch’s beggar Benjamin, who has undergone a bit of a makeover and now resembles the many blue-eyed Christ figures of earlier biblical epics and numerous pieces of religious art both high and low. While Benjamin has up to now been largely a tangential figure, he now gets to offer up yet another helping of cynicism, which is in marked contrast to Samuel’s own newfound faith.

However, one feels about the film’s tonal shifts The Book of Clarence deserves a great deal of credit for being willing to take such significant risks in storytelling (something that even more ambivalent critics have noted). The biblical epic is a genre renowned (and sometimes reviled) for how seriously it takes itself and its subject matter, and it’s also one that is notable for its rigorous adherence to Whiteness. The Book of Clarence works very hard to use the conventions of the genre itself and, while not every single moment works, as a whole I think the film succeeds because it manages to both poke fun and also revere its source material. It’s the kind of film that stays with you long after the final role, asking you to grapple with the nature of faith and its influence in the modern world.

Like all good biblical epics, The Book of Clarence draws on the present to give texture and potency to its story about the ancient past. Just as he brought Black people back into American history through the western in The Harder They Fall, so Samuel has brought BIPOC into the ancient world epic. The result is a triumph, and let us hope that the film gets the respect and acclaim it so richly deserves.