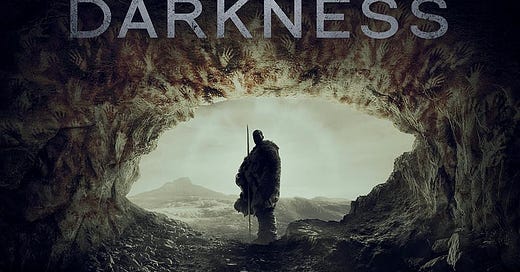

Film Review: "Out of Darkness" and the Primal Fear of Being Human

The debut feature from Andrew Cumming forces its human viewers to confront the terrors and fears that are foundational to our species' collective imagination.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Spoilers are ahead!

For me, the best horror films are those which make you think differently about the world. Yes, the scaries are all well and good–and I don’t mind a nice slasher flick now and then–but for me the horror films that really stick with me are the ones that capture or convey something meaningful about the human condition. Annihilation remains one of the hallmarks of my own personal horror canon, and it is now joined by Out of Darkness, the feature directorial debut by Andrew Cumming.

Set 45,000 years ago, it focuses on a small group of prehistoric humans who have fled their homeland and washed up on strange shores. They are led by Adem (Chuku Modu), who is joined by his younger brother Geirr (Kit Young of Shadow and Bone fame) and his son, Heron Luna Mwezi). Rounding out the troop are Adem’s consort Ave (Iola Evans), elder Odal (Arno Luening), and “stray” Beyah (Safia Oakley-Green). At first it seems as if they have come to a new promised land but, very quickly, it’s clear that not only is this land harsh and inhospitable; it is also haunted by a ghastly presence that screams in the night.

As Alison Foreman says, there’s something very Joseph Campbell about these characters, in that they so neatly fit into deep-seated archetypes of human storytelling and sense-making. At the same time, however, the (relatively-unknown) actors bring a remarkable emotional depth to their characters. There are feuds and divisions and disagreements galore within this tight-knit group, whether it’s Ave’s resentment of her stepson (she pointedly tells him he’s not his mother when he asks for a story) or Beyah’s distrust of Adem after he shows an erotic interest in her. These are conflicts that would feel at home in the present, but they take on an added urgency in this prehistoric milieu, in which human life is always in a state of precarity.

At the formal level, Out of Darkness is the perfect meeting of image and sound. The Scottish Highlands, with all of their majestic and brutal beauty, are the perfect setting for this tale of primal fears and the struggle to survive. Several times the camera glides overhead, juxtaposing the soaring heights of the mountains with the small human figures making their painstaking way across the unforgiving landscape. For me, though, the most terrifying thing about the whole film was its sound design. The constant thrum of the music keeps you perpetually unsettled and on the edge of your seat, adding to the sense of immersion in this uncanny and strange new world.

There’s something primordially terrifying about this film, something that digs deep into our collective psyche, excavating our angst about who we are as a species. To be sure, much of the film’s terror stems from the fast-moving and screeching enemy that assails the company and kidnaps Heron, dragging him off into the darkness. However, as the band of survivors tries to find him, the editing and lighting (many of the scenes take place in near-complete darkness) continue to make both us and the characters uncertain about just what kind of world this is and what might be living in it.

Out of Darkness is mercifully short on gore and bloodshed, though there are a few moments of terrifying violence, particularly once Adem and the rest of the company enter the sinister forest they have so far avoided. In addition to discovering a cesspit, Adem makes the unwise decision to pursue the creature into the darkness, and its attack leaves him horribly disfigured and dying. There’s something almost poignant about seeing Adem’s sculpted male beauty ruined, left to the brutal mercy of Beyah, who ends his life when Geirr can’t bring himself to do so. Shortly thereafter they resort to eating his flesh in order to survive, though Geirr once again abstains, remarking that they don’t eat their own because they are not monsters.

This desperate cannibalism is the most haunting demonstration of just how far they have fallen. In many ways, they are no better than the beast they continue to pursue, as Odal demonstrates when totally succumbs to the temptation to superstition, leading Ave to join him in sacrificing Beyah to the demon. In these taut moments the film brings out the perilous tension between civilization and barbarism, between humanity’s higher instincts and its restless, destructive id. Odal’s stabbing of Ave–and subsequent offering of her to the beast–further signifies his descent into the darkest religious impulses of the human mind.

This ongoing tension only increases once the monster is finally revealed: rather than some reptilian horror it is instead a Neanderthal woman, who has been moving quickly through the forest with a mask on her face. Geirr and Beyah follow her to her cave, where more bloodshed and terror follows; Geirr is killed but so are the Neanderthals, while Beyah succeeds in rescuing Heron, who has been kept by them all along.Beyah learns too late, the Neanderthals were merely trying to help Heron; seeing the child starving and near to death, they took him in. They have also wrapped Ave’s body and prepared it for burial. Therein lies the central contradiction of the film: those who are seemingly the most inhuman have, at least to an extent, shown more compassion than the humans themselves.

Having turned this new world and its harsh hospitality into a place of death and ashes, it falls to Beyah and Heron to try to rebuild this world. As Beyah tells Heron that they will “try again,” she stares off into the camera. However optimistic her words might be, the sad and devastated look on her face suggests that the destruction of the old one will forever haunt her. Modern humans might have triumphed in the end, but at a terrible physical and spiritual cost. As Foreman notes, at the heart of the film is “humanity’s original sin.”

As Glenn Kenny notes, the film is “ultimately sad more than terrifying, and I would take this a step further and suggest that there is also something deeply tragic about Out of Darkness, in the classic sense of the term. Adem and his people sought a new world where they could flourish, and Beyah wanted a family, having been cast out of society. As she herself says, she only discovered she had found a new home and family when it was too late. Ultimately, Out of Darkness is a powerful reminder of the dangers of heedlessly destroying that which we don’t understand. Stabbing first and asking questions later might seem justified in the moment–the Neanderthals do kidnap one of their own, after all–but is their slaughter and the destruction of their home adequate recompense?

Like the best horror films, Out of Darkness holds up a light to our contemporary world, forcing us to recognize and make peace with our species’ propensity for destruction and death. Humanity is not only its own worst enemy; it’s also the bane of others with whom it comes into contact. This is a humbling but necessary message for the modern age.