Film Review: "Napoleon" and the Violent Absurdity of Power

Ridley Scott's new epic shines a powerful light on the way great power breeds great ridiculousness and mass annihilation.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

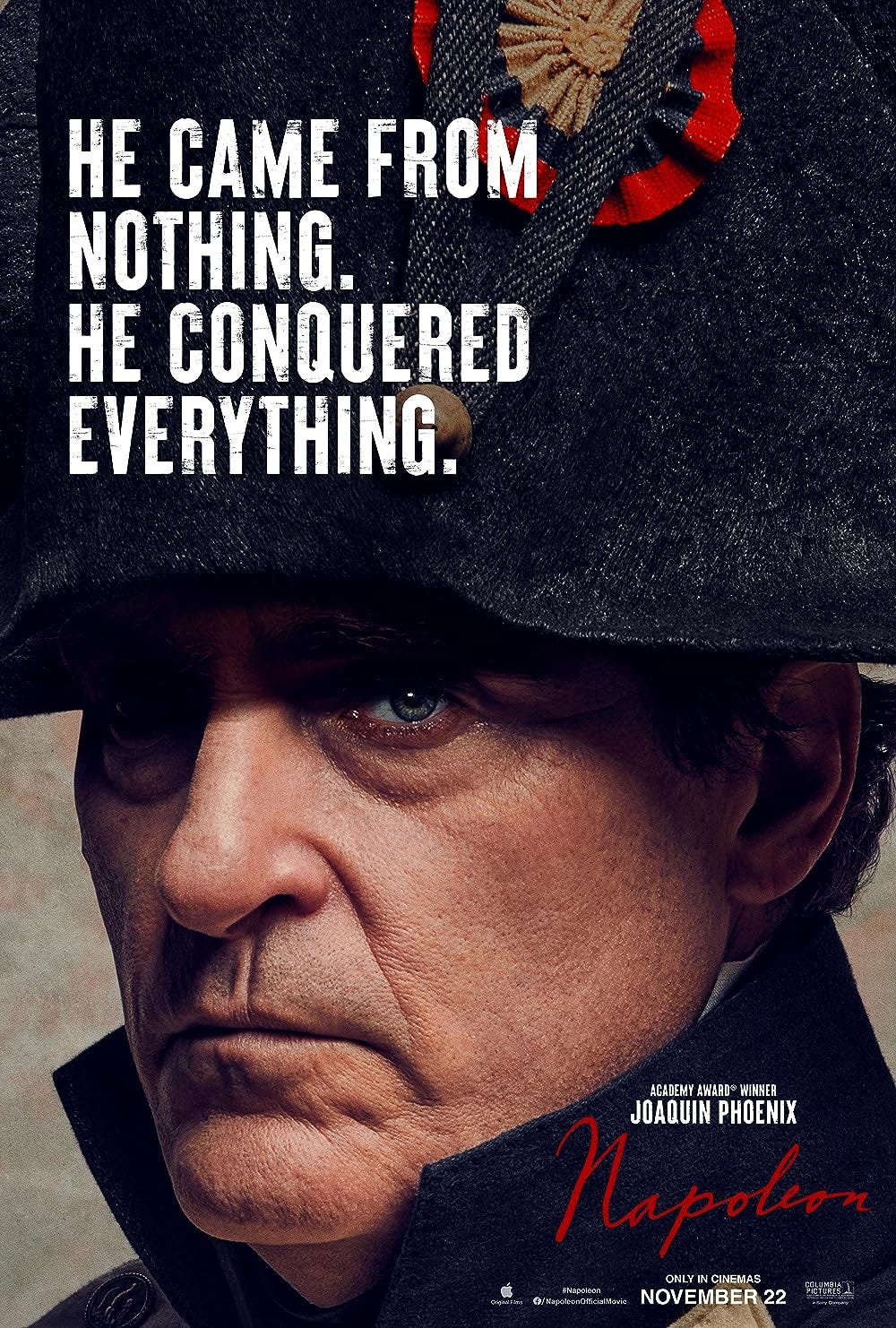

If there’s one filmmaker working today who has proven time and again that he understands the power of the historical epic as a cinematic form, it’s Ridley Scott. Though not every one of his big-budget spectaculars has risen to the level of Gladiator–looking at you, Exodus: Gods and Kings–for the most part he has the epic filmmaking sensibility in his bones. What’s more, as someone who understands the genre–its conventions, its ideologies, its assumptions–Scott is also uniquely primed to subvert them, something he proved with remarkable skill in The Last Duel. He now accomplishes something even more daring and audacious in his bluntly-titled Napoleon. Rather than producing a hagiography of one of Europe’s most (in)famous conquerors, he instead uses this epic to expose the absurdity and violence of power in all of its most malignant forms.

When the film begins Napoleon is a rather unremarkable soldier. After bearing witness to the gruesome execution of Marie Antoinette, he soon starts to climb the ladder of power, and his career really takes off once he leads the enormously successful Siege of Toulon. Despite some setbacks he is soon perched atop the French Empire. However, after a series of military victories he faces a devastating loss at the hands of the Russian Empire, which leads to a short exile in Elba, after which he briefly returns to power before being definitively beaten at Waterloo and exiled to Saint Helena, where he dies in obscurity.

Throughout the film Joaquin Phoenix is a strange delight. He has always excelled at playing twitchy characters with fantastically large egos, most notably the deranged and daddy-hating/loving Commodus in Gladiator, but he really outdoes himself here. His Napoleon is surly and distant and utterly ridiculous, someone who can never quite overcome the gaping hole of inferiority at his heart. The film doesn’t really give us much insight into what makes him such a military genius, but what it does do is demonstrate just how ridiculous he is.

Take, for example, the moment when he finally becomes First Consul. What should be his crowning achievement is instead a barey-controlled fracas, after various members of the ruling class rebel and chase Napoleon out of the building, reducing him to nothing more than a sad and doddering spectacle. It’s only the quick thinking of his brother that saves him from ignominy, as he orders the soldiers to storm the building. Napoleon might go on to crown himself Emperor in suitable pomp and circumstance–even going so far as to take the crown from the pope and put it on his own head–but even this is not enough to wash off the stain of silliness.

The real coup de grâce, however, occurs when Napoleon rides into Moscow only to find that it has been completely abandoned by his Russian foes, and things veer into the sublimely absurd when he enters a grand palace to find it echoing and playing host to a flock of pigeons. The moment is piercingly and bitingly funny. Here is Napoleon, someone who is utterly convinced of his own rightness and his own glorious destiny, sitting in the abandoned ruins of Moscow, in the very seat of tsarist power, while pigeons literally poop on everything around him. It’s the film’s purest articulation of how absurd power is, and how it can lead even a man like this one, with all of European power at his command, to become nothing more than a figure of mockery. To add insult to injury, poor Napoleon can do nothing more than watch in stupefaction (and even reluctant admiration) as the splendid capital burns down around him.

Things only go from bad to worse, for though Napoleon does manage to claw back some measure of victory, he ultimately can’t stave off defeat at Waterloo, which leads him once more to exile, this time on the even more isolated Saint Helena. The film’s final scene features Napoleon in exile on St. Helena, where he labors over his memoirs and corrects children about their supposed misunderstanding of history. He then tumbles out of frame, having finally been felled by death. It’s a suitably ignominious death for someone who, as the film’s ending card makes clear, was responsible for millions of deaths.

However, Napoleon isn’t the only one that the film ridicules. Robespierre, architect of the tear, experiences a fall as meteoric as his rise and, faced with utter destruction–and a public humiliation at the end of a guillotine blade–tries to take his own life with a gunshot. Unfortunately, he only grievously wounds himself in the face, rendering himself into an even greater spectacle than he would have had simply accepted his fate with good grace. Louis XVIII, the restored Bourbon monarch (played by a criminally underused Ian McNeice), can only quail in ridiculous fear when Napoleon returns from exile. Even Lord Wellington, the architect of Napoleon’s catastrophic defeat at Waterloo isn’t a paragon of British nobility; instead he’s a bit of a boor himself. (Rupert Everett has recently excelled at playing such characters. See also his turn as Emperor Charles V in The Serpent Queen).

If there’s one character who isn’t absurd, it would be Vanessa Kirby’s Joséphine, the Indeed, she takes every chance she can to cut her imperial husband down to size and, while he might seem to wear the pants in their family, it quickly becomes clear just how much he relies on her love and approbation. He is nothing without her, and they both seem to realize this. The film features numerous scenes of their awkward lovemaking, and it becomes very quickly clear why Joséphine takes a lover (what remains more inexplicable is why she seems as devoted to him as he is to her).

At the same time as it emphasizes just how silly and absurd autocrats are–all the more so when they take themselves as ponderously seriously as Napoleon takes himself–Napoleon also highlights the violence, blood, and brutality inherent in power and those who seek it. If any film of recent memory captures the essence of Hegel’s notion of the slaughter-bench of history–or Benjamin’s angel of history, for that matter–I would argue that it’s Napoleon. Our first truly gruesome scene features a brutal moment in which Napoleon’s horse is disemboweled by a cannon-ball (which he extracts and hands to his brother so the latter can take it to their mother), and Scott repeatedly draws our attention to just how many people perished in the pursuit of Napoleon’s ambitions. With great power, it seems, comes great annihilation. The fact that it ultimately serves no other purpose–refer again to the ignominious and anticlimactic circumstances of Bonaparte’s death–makes the death toll even more egregiously ridiculous.

Sprawling and beautiful and brutal, Ridley Scott’s Napoleon reminds us once again of the power of the epic film to force a confrontation with the ugliest elements of the past.