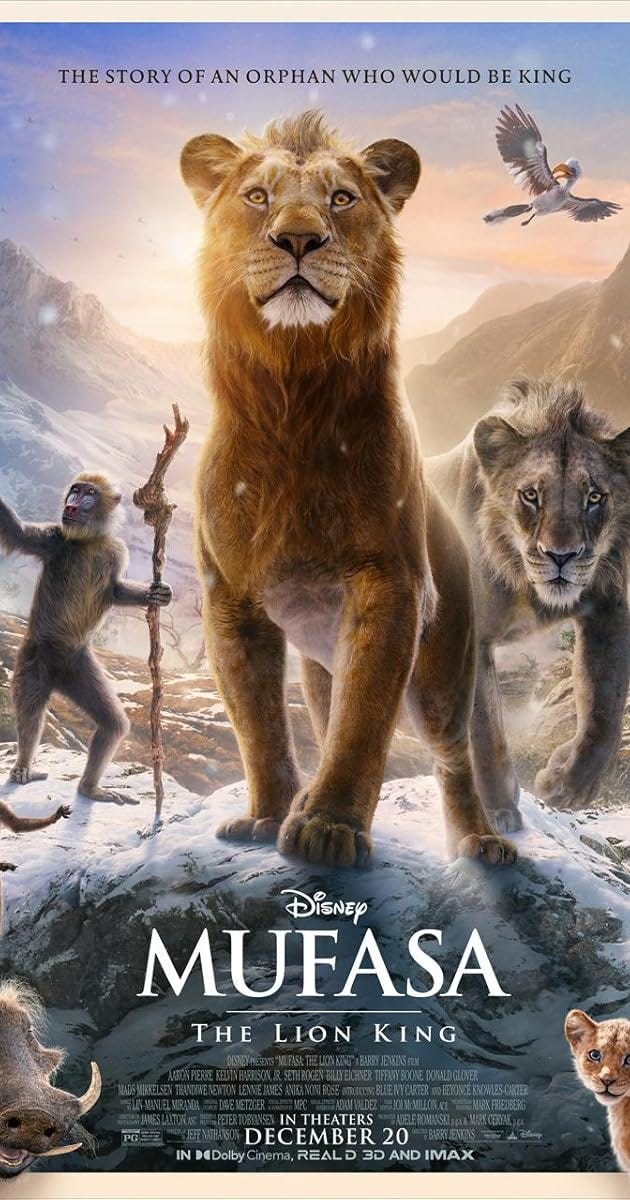

Film Review: "Mufasa: The Lion King"

With Barry Jenkins at the helm, this Disney "live action" prequel ends up being much better than it has any right to be.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

It will come as no surprise to anyone that I went into Mufasa: The Lion King with very low expectations. I’ve never been a fan of Disney’s live-action remakes, and I continue to think the studio would be better served–in the long term, at least–by investing more in original stories rather than continuing to till the same row time after time in an attempt to squeeze every bit of money out of its various properties. Still, I’ve also been of the opinion that these remakes do best when they’re not slavishly beholden to their originals (see also: The Jungle Book and Pete’s Dragon).

Thus, I found Mufasa to be a surprising pleasure, thanks to some animation that’s more vibrant than in its predecessor, a script that’s light on its feet (sometimes a bit too light, but more on that in a moment), some decent songs from Lin-Manuel Miranda, strong vocal performances, and skilled direction from Barry Jenkins. While I don’t think this film will ever be a classic, I was quite entertained. Given the lack of any creative energy coming out of the House of Mouse these days, that’s no small thing.

Framed as a story being related from Rafiki (John Kani) to Simba’s daughter Kiara (Blue Ivy Carter), Timon (Billy Eichner), and Pumbaa (Seth Rogen), it follows the young Mufasa (voiced as a cub by Braelyn and Brielle Rankins and as an adult by Aaron Pierre) after he is separated from his parents and adopted by Prince Taka (Theo Somolu as a cub and Kelvin Harrison Jr. as an adult) and his pride. The two forge an extraordinary bond, until it is tested and ultimately broken after their pride is savaged by a group of white lions led by the sinister Kiros (Mads Mikkelsen). They join with Sarabi (Tiffany Boone), a young Rafiki (Kagiso Lediga), and Zazu (Preston Nyman) as they seek the fertile valley known as Milele.

To some degree an animated film like this one lives or dies based on the strength of its voice cast, and in this regard Mufasa excels. Both Aaron Pierre and Kelvin Harrison Jr. fit neatly into their roles, with the latter adopting a harsher and more sinister tone as the film goes on and Taka begins to feel the bite of Mufasa’s natural gift for leadership and his bravery. Lediga is also perfectly cast as the younger version of Rafiki, endowing the character with both the wackiness that has always been key to his characterization as well as some remarkable and surprising depth. And, of course, there’s Mads Mikkelsen, who never met a villain he couldn’t play to the hilt. The film is worth the price of admission just to hear his menacing purr as he brings doom to any who stand in his way.

Unlike the “live-action” Lion King, Mufasa is actually a remarkably beautiful film, with sweeping vistas of the savannah and breathtaking views of the towering mountains that Mufasa and company must cross as they make their way to Milele. Jenkins has always had a keen eye for a striking image, and he brings his considerable aesthetic vision to bear throughout Mufasa. The film is filled with many extraordinary visuals, many of which, unsurprisingly, take place underwater (when Mufasa is swept away by a flood early in the film, when he falls into a giant underground lake in Milele, etc.) There’s a lot of religious imagery here, and it helps to buttress the sense that Mufasa, at least in the mythology of The Lion King, was truly a world-changing figure of vast historical importance.

For the most part the screenplay is well-developed without getting bogged down, and it keeps the story moving along at a nice pace. There were a few bits that I felt could have been more fully developed, most notably Taka’s fondness/love for Sarabi, which ends up being the thing that finally and permanently shatters his relationship with Mufasa. I just never bought the idea that Taka had strong emotional feelings for anyone other than his adopted brother, and it rather felt as if the film couldn’t find a more compelling reason for the two to have become such potent enemies later in their lives (it also robs Taka/Scar what little remained of his queerness from the original film, but that’s a separate essay).

I’m also a bit mixed when it comes to the framing device. Eichner and Rogen are obviously quite funny and charming and self-aware (they were a highlight of The Lion King, as well), but the constant shuffling to the present tends to break up the narrative propulsion. Moreover, a little of their schtick goes a very long way, and it too often seems to drain the Mufasa portions of their grandeur and emotional depth. Sometimes, it’s okay to just let your story stand on its own without needless callbacks to a film we already know exists (and, as with so many other films that are mining existing IP, this one loves callbacks to The Lion King, particularly when it comes to Taka saving Mufasa by digging his claws into him as he dangles perilously above his doom).

That being said, I did enjoy the way that Mufasa took some risks when it came to its central message. Unlike so many other recent Disney productions–such as the Star Wars sequel trilogy–Mufasa takes a very different political point of view when it comes to bloodlines. In this version of events Mufasa is common while Taka is from the blood of kings, and the early parts of the film make quite a lot of this distinction, particularly since Taka’s father has nothing for contempt for strays and any others who don’t enjoy exalted pedigrees. Unfortunately for Taka and his father, the young prince is at heart a coward, and it’s this cowardice that ultimately hardens his heart and poisons his mind so that he betrays the brother he supposedly loves. His destiny and his royal blood is no match for Mufasa’s natural gift for leadership, and the film uses this to structure its Shakespearean plot with strong results.

Songwise it’s fine. Lin-Manuel Miranda is, obviously, a talented songwriter. His tunes for this outing are entertaining enough, but I’d be hard-pressed to remember any of them. As with many other aspects of the film, they do the job, and that’s enough.

Overall, I quite enjoyed this film. It’s far better than it has a right to be, and it just goes to show that these live action remakes can capture at least a little bit of the old Disney magic when they’re allowed to paint outside the lines a bit (for a further discussion of its success in this regard, check out Matt Zoller Seitz’s review). Unfortunately, the film stumbled in its first weekend at the box office but, given that it seems to have earned a decent enough “A-” on Cinemascore, it may yet have legs. Even so, one can’t help but wonder whether Disney will take the wrong lesson from this mediocre performance and shift away from anything even remotely resembling originality when it comes to their mining of their existing IP. Or, just perhaps, it’ll force them to start reinvesting in original material.

Hope, as they say, springs eternal.