Film Review Double Feature: "Wicked" and "Gladiator II"

These two films, dubbed "Glicked," say much about the current state of America, in all of its beauty and ugliness, its triumph and its despair.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Full spoilers for the films follow.

Welcome to a very special edition of Omnivorous, wherein I review both Wicked and Gladiator II. These two films, in their very different ways, reflect our world in all of its beauty, ugliness, and complexity, and so it was a real pleasure getting into the nitty gritty of what makes them work and where they fall short.

Given that I have loved the musical Wicked since I first listened to the cast recording as a baby gay in 2005, it was probably inevitable that I was going to at least like the film version, even if its trailers didn’t really do it many favors. What I did not expect, however, was just how much I was going to fall in love with it. From its very first moments it cast a spell on me, filling me with that strange and heady mix of emotions that always accompanies any experience I have with Wicked: happiness, joy, sorrow, and everything in between.

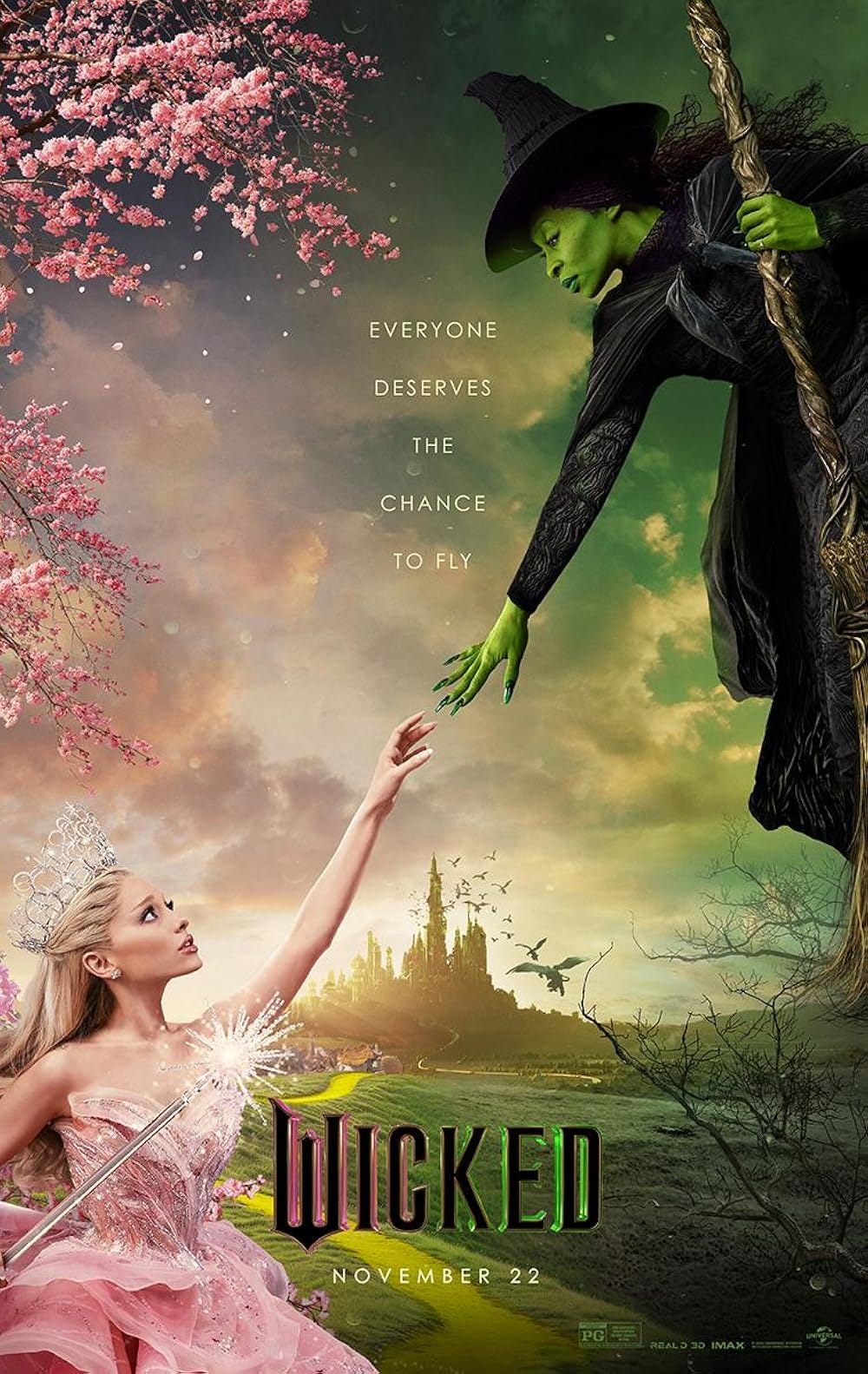

As most people know by now, this adaptation covers the first act of the stage play (the second half will be coming almost exactly a year from now). After an opening number announcing that the Wicked Witch of the West is dead, the rest of the film proceeds to document the bond between blonde, perky, and very popular Glinda (Ariana Grande-Butera) and green-skinned, bookish, and decidedly unpopular Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo). At the same time, there is a growing movement led by the Wizard of Oz (Jeff Goldblum) and the cynical Madame Morrible, to deprive Animals of the Power of speech and make them into second-class citizens and thus a useful distraction from the fact that he has no real power. These two strands collide in the film’s third act, with cataclysmic results.

I’ll be the first to admit that I was a little nervous when I saw that Ariana Grande-Butera had been cast as Glinda. However, from the moment that she descends in her little glistening bubble to “rejoicify” over the death of the Witch, it’s clear that we are dealing with a very remarkable talent, and she excels at capturing Glinda’s mixed feelings at this moment. You can see right away that the Good Witch is haunted by everything that transpired before the film even starts, and I can't get the haunted look in her eyes out of my head. Like so many other people who have made deeply questionable moral choices at times of heightened political turmoil, she has to reckon with the fact that the woman that she loved and with whom she formed such a strong bond has been sacrificed on the altar of her own ambition.

However, Grande-Butera also excels at the lighter moments, too. While Wicked doesn’t shy away from the darker elements of the original story, it’s also a marvelously funny film, particularly in numbers like “What is this Feeling?” and “Popular” the former of which has to be one of the greatest love songs in the history of musical theater (I said what I said). The grumpy/sunshine dynamic between Elphaba and Glinda has always been one of the best things about the show, and such is the chemistry between Grande-Butera and Erivo that they manage to capture the hilarity and the heartache of the Elphie/Glinda relationship.

Of course, it probably goes without saying that Erivo is also truly sublime as Elphaba. This is the type of role that really does demand that a performer pour everything of themself into it, and from the moment we meet her it’s clear that Erivo has done just that. Whether it’s belting out the soaring notes of “The Wizard and I,” the softer longing of “I’m Not that Girl,” or the power ballad of rebellion “Defying Gravity,” Erivo can do it all. And, as many have noted, it’s particularly powerful that this is a young Black woman portraying this role, giving even more layers to Elphaba’s status as an outsider in the increasingly unstable and dangerous Oz.

The rest of the cast is also universally excellent. As one reviewer pointed out, Jonathan Bailey continues to show that he’s the kind of actor who has chemistry with literally anyone he’s on screen with, whether that’s his two main co-stars or any of the extras with whom Fiyero flirts relentlessly as he performs “Dancing Through Life.” The only downside is that there’s not a lot for Fiyero to actually do after his number is over, but I’ve got my fingers crossed that they manage to beef up his role in the second part.

Both Jeff Goldblum and Michelle Yeoh are also deliciously villainous as the Wizard and his cunning, ruthless minion Mrs. Morrible. Goldblum is always a spritely delight whenever he’s on-screen, and he puts his oddball charisma to very good use as the Wizard, a man who knows all too well that he’s nothing more than a charlatan and thus decides that the best thing to do is to enlist the help of the residents of Oz in rendering Animals into scapegoats, thus solidifying his own power. Yeoh is also icily terrifying from the very moment that she sweeps onto the screen, ready to try to manipulate Elphaba into becoming another agent of state power.

This is a musical, though, and so one comes into Wicked expecting no small amount of song, dance, and utopian euphoria, and the film has this in spades. Again, the trailer doesn’t really do it any favors, and you’d be forgiven for thinking that this was going to be a very visually dull film (director Jon M. Chu’s comments about wanting to make the film more realistic haven’t helped). However, I was pleasantly surprised by just how beautiful the film was, particularly on the extra large RPX screen). There’s also some fantastic choreography, particularly during both “What is This Feeling” and “Dancing Through Life,” both of which are truly show-stopping numbers of excess and the simple, utterly liberated joy of song and dance. There are some numbers, particularly “The Wizard and I” and “Defying Gravity” that will truly knock your socks off, and I know I wasn’t the only one who had tears in my eyes during almost the entire movie.

Yes, it really is that moving.

This isn’t to say that Wicked doesn’t have some smart things to say about the world, because it most certainly does. Some reviewers have already started criticizing the film for its inclusion of the Animal rights subplot, with some suggesting this darker tone is at odds with the frothier musical elements. I must confess that I’m a bit stumped by this particular line of criticism, since Elphaba’s belief in the rights of Animals is the prime motivator of the plot–and the rift that eventually opens between her and Glinda. For that matter, it’s her devotion to the Animal rights cause that leads her to rebel against the Wizard, at significant personal cost to herself.

Perhaps, though, there’s a simpler explanation. Some people just can’t wrap their heads around the idea that a musical–a supposedly escapist and lighthearted genre–might have something meaningful to say about politics and the state of America today. Even though Wicked was well in the works before the results of the election, and even though the book and the play are already decades old, this is one of those films that still manages to capture the zeitgeist in much the same way that Barbie did a year ago. Not to get too allegorical, but one doesn’t have to squint to see more than a bit of our soon-to-be Charlatan in Chief in Goldblum’s Wizard, a man who ultimately has very little power and almost no ideological investments except for uniting the people of Oz against a common enemy. There’s also something more than a little chilling about the moment when Madame Morrible makes an announcement to the residents of Oz that Elphaba is now the Wicked Witch, a message which everyone–even Elphaba’s own sister Nessarose (Marissa Bode)--seems all too willing to wholeheartedly believe.

The power of a film like Wicked stems from its ability to be escapist and deeply invested in the problems of the present. There’s no question that “Defying Gravity” has always been a song of empowerment, but it gains an extra valence in the present, when a Black woman was once again waging a battle against a wannabe tyrant even as there were far too many people who wanted to dismiss her, to call her a witch and worse, to celebrate once she was defeated in the election. Given the heady confluence between the real world and the film’s narrative, it’s easy to see why so many have found it to be cathartic.

Suffice it to say that I was quite overwhelmed by Wicked, in the best way possible. There was just so much about this film that brought me joy, from the cameos from Idina Menzel and Kristin Chenoweth to the final number. And I’ll be honest with you, dear reader. I was in tears almost from the very beginning, and it didn’t let up until the end. That, to me, is the mark of a truly great piece of musical filmmaking.

All of this begs the question: what will be in store for us in the second part? Even Wicked’s greatest fans admit that the second act is much weaker than the first, but I have high hopes that, with an expanded runtime and further elaboration by Winnie Holzman and Dana Fox, will give us a rousing conclusion that we can all adore.

Now, on to Gladiator II. As with Wicked, Gladiator has long been a part of my life. I loved the original movie long before I decided to make studying the reception of antiquity in cinema my major field of study, and there’s no doubt that it remains a remarkable piece of epic cinema. Thus, it’s probably not surprising that I was also very excited about the sequel, particularly since it has languished so long before finally seeing the light of day. Well, now it’s here and I’ve seen it, and I regret to say that, while I did indeed find it very entertaining, it also lacks that certain spark that helped to make the original such a success. Much as I wish it were otherwise, it simply can’t overcome its own slavish devotion to its predecessor, and its very slapdash story does it no favors.

When the film begins Paul Mescal’s Hanno (who is secretly Lucius Verus Aurelius, the illegitimate son of Russell Crowe’s Maximus and Connie Nielsen’s Lucilla), is living in exile in Numidia, having been sent there by his mother to keep him safe. However, a Roman army led by General Acasius (Pedro Pascal) conquers his home city, killing his wife in the process, after which he is bought by gladiator maestro Macrinus (Denzel Washington), who aims to use him as a weapon to destroy both Acacius and the corrupt, feckless twin emperors Caracalla (Fred Hechinger) and Geta (Joseph Quinn). Meanwhile, Lucilla plots to topple the corrupt despots and return Rome to the people, thus bringing her father’s dream to fruition.

At first, I was quite swept up in the majesty and the kinetic pleasures that this sequel offers. Scott has lost none of his visual flair, and while some of the scenes in the arena are truly ridiculous if you think about them–I mean, the film does feature a scene involving feral baboons and the use of sharks in a flooded Colosseum–they are still quite thrilling. However, it’s also worth pointing out that a little goes a long way when it comes to such things, and it becomes clear at about the halfway point that this film doesn’t really believe in its own central story, which is why it leans so heavily on the spectacle, in the hopes that the audience will just forget about the plot hole and go along for the ride.

The performances, too, are quite remarkable. Though many others are inclined to unfavorably compare Paul Mescal to Russell Crowe, I actually think he more than holds his own in his role as Hanno. He brings the same wounded soulfulness that he’s shown in his roles in such films as All Of Us Strangers to Hanno, and while his battlefield speeches may not have the same effortless gravitas as those of Maximus, he more than holds his own in the rare quiet scenes that the film offers. One can easily imagine a very different kind of film, one which didn’t kneecap its leading man by forcing him to tread in the shadow of his predecessor.

There’s no question, though, that this is Denzel Washington’s film, and I constantly found myself wishing (as others have done) that this was instead about his own rise to power and the desperate lengths to which he is willing to go to get it. Of course, this film was made in a Hollywood laboring under the tyranny of IP and sequels, so it was inevitable that it was going to feel the urge to follow in well-trodden footsteps, but you can still see Washington’s incandescent star power and remarkable performances always threatening to burst out of the limits–and often nonsensical plot convolutions–the film constantly imposes on him.

Now, on to the politics.

As a rule I’m not one of those who thinks that every film has to be pored over for its ideological messages but, let’s be real, when you’re talking about Gladiator II (and its predecessor), the film essentially asks you to take something away from it when it comes to messages about the present. While Sir Ridley may not ever be particularly invested in historical accuracy, the man does deserve at least some credit for making historical epics that are willing and able to engage with the politics of the present, whether that’s late-20th century angst in the OG Gladiator, the War on Terror in Kingdom of Heaven, or the foibles of foolish leaders in Napoleon. Gladiator II is no exception in this regard, though what it has to say about politics ends up being much less compelling or sophisticated than in much of the rest of Scott’s oeuvre.

Unsurprisingly, the film makes much of the fact that its three villains–Geta and Caracalla on the one hand and Macrinus on the other–are, shall we say, not exactly paragons of traditional masculinity. The twin emperors are suitably deranged and sometimes downright silly, with their garish white face paint, blonde locks, and unhinged behavior (Caracalla even goes so far as to make his pet monkey a consul, a clear callback to the antics of Caligula). Macrinus, meanwhile, is a queer bird of a different feather: far more cunning and ruthless than the hopeless emperors, by his own admission he’s not above having a dalliance with a man or two and, just as importantly, he has arguably the best wardrobe in the entire movie. I’ll have more to say about this film’s engagement with the politics of queer villainy in next week’s Sinful Sunday, but for now let me say that Macrinus is the type of queer villain that I live for, while Caracalla and Geta are ultimately too foppish and forgettable to really make much of an impact.

In this case, I’m less concerned with the film’s trafficking in stereotypes about queer folks and the danger they pose to the body politic than I am with Gladiator II’s racial politics. Maybe it’s just that I watched the film in the aftermath of the 2024 election, but I couldn’t help but cringe when Macrinus revealed that he had once been Marcus Aurelius’ slave and that his power grab was in some ways motivated by a desire to get revenge. This makes his final defeat at Hanno’s hands–and if you’ve seen the film you’ll see what I did with that pun–all the more grating and oddly relevant, given that Trump’s rise to power was motivated at least in part by both his own and his voters’ anger that a Black man dared to be president. I wouldn’t have even thought about it in this way if the story hadn’t gone out of its way to demonstrate that Macrinus is that most dangerous thing in Hollywood cinema: a Black man with agency. It’s obviously a good thing that the ancient world epic is finally starting to acknowledge the diversity of the ancient Mediterranean in a meaningful way, but one could hope that they could have done so without ultimately vanquishing this upstart so that the true heir to the Roman throne could take his place.

What’s more, as a friend of mine pointed out, Gladiator II suffers from the same limited vision as the Star Wars sequel trilogy, in that it is so wrapped up in the mythos of its original–and of Maximus and of the entire Antonine bloodline–that it can never really see itself out of this quandary. There’s something particularly ironic about the fact that the film goes out of its way to suggest that, somehow, it’s only Marcus Aurelius’ bloodline that can somehow save Rome from itself when we’ve been given absolutely no indication that this is the case. Lucilla and Senator Gracchus may be very noble, but they’re surprisingly inept when it comes to plotting, so perhaps it’s fitting (if frustrating) that they are both quite quickly dispatched in the arena. (A side note: Macrinus is the one who actually kills Lucilla, yet another way in which Gladiator II dabbles with Hollywood’s racist tropes, in this case the Black man menacing a White woman).

At the same time, Gladiator II isn’t a particularly coherent film when it comes to its narrative. Again, I’m not one of those who thinks that a film needs to answer every question or have an immaculate screenplay. At the same time, this one does make some questionable storytelling choices. To take just one particularly vexing example, the film ends with Hanno miraculously convincing the armies of Rome to lay down their arms. Even accounting for the suspension of disbelief that’s always a key part of enjoying a film like Gladiator II, this does seem more than a little tacked on and ridiculous.

I suppose what it comes down to is this. While I wouldn’t go so far as to say that this sequel tarnishes the reputation and legacy of its predecessor–that would be a rather limited and ultimately not particularly convincing argument–I do think that its story makes one wonder just what the point of Maximus’ journey was. As the opening title makes clear, Maximus’ death didn’t see the restoration of the Republic but instead just to another cycle of bloodletting and tyranny. This might be historically accurate, but it nevertheless suggests there is no escape from the brutal nature of history itself. It also raises some troubling questions about the nature of what Hanno himself has managed to accomplish. Who’s to say that his efforts to build a more cosmopolitan and egalitarian Rome will be any more successful than those of the heroes who preceded him?

A braver film than Gladiator II might have meaningfully engaged with these questions but, instead, we get an outing that ultimately ends up being a pale imitator of its illustrious predecessor.

Thank you for joining me for this special double feature. I’m sure I’ll have many more things to say about the two films that have been dubbed Glicked, so be sure to follow me on social media. And, if you’re feeling really ambitious, subscribe to this very newsletter!