Film Review Double Feature: "A Complete Unknown" and "The Last Showgirl"

Two new films, anchored by terrific performances, showcase the double sword that is fame and public performance.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Full spoilers for the films follow.

It’s another double feature here at Omnivorous, and this week I’m focusing on a pair of films that explore artistry, fame, and the price people pay for their time in the spotlight.

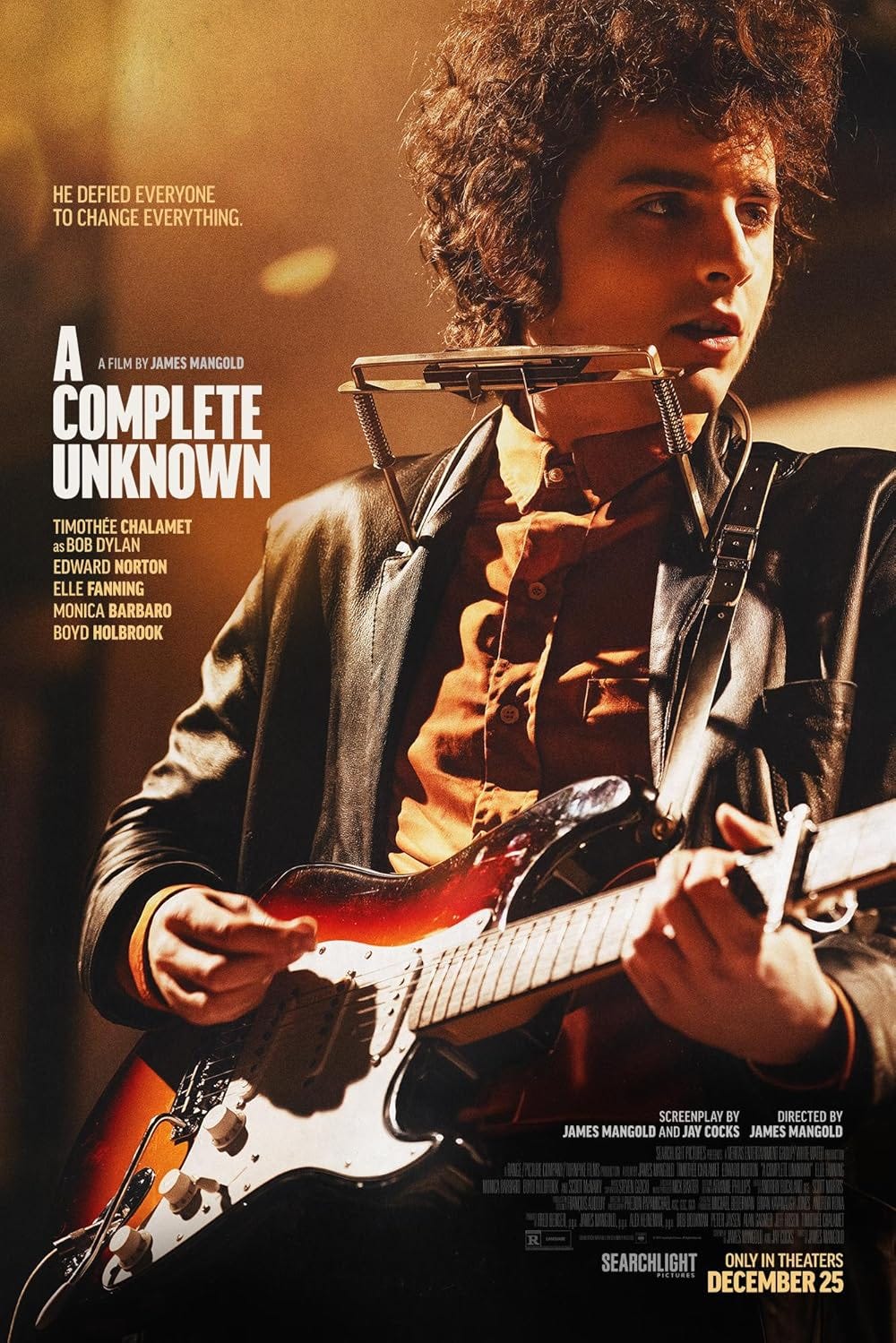

I’m a sucker for an Oscar-bait movie, and they don’t come much more Oscar-baity than A Complete Unknown, the new musical biopic focusing on the early life and career of Bob Dylan. While the film certainly has its flaws–particularly when it comes to its narrative, which isn’t particularly revealing–it’s nevertheless an eminently watchable film, one anchored by strong performances and, near the end at least, a bit of commentary about the less-than-salutary effects of great fame.

When the film begins Dylan is a drifter of sorts, blowing into New York City to seek out his hero, Woody Guthrie (Scott McNairy), who is ailing in a New Jersey hospital. After his fateful encounter–which also sees him crossing paths with Edward Norton’s Pete Seeger–he soon becomes a fixture in the folk music scene. It’s not long before he’s rocketing to the top of the charts, attaining the enormous success for which he would become famous. As his fame rises, however, Dylan finds his own artistic desires thwarted by both the powers-that-be in the folk community and by his own audience, particularly once he turns to electric guitar.

Obviously one of the film’s biggest selling points is Chalamet himself, who gives what can only be described as a totally embodied performance as Dylan. It’s not just that he has the man’s physical and vocal mannerisms down–though that is true–but more that he seems to inhabit his enigmatic appeal. This, though, is both the film’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness. Just as Dylan remains something of a mystery even now, so Chalamet’s character also resists any attempts to really understand him, either by the characters in the film (both Monica Barbaro’s Joan Baez and Dylan’s girlfriend, Elle Fanning’s Sylvia Russo, seem by turns befuddled and infuriated by him) or by us in the audience. A great performance like Chalamet’s deserves a more insightful and thoughtful screenplay.

Edward Norton also has a charming and nervous energy as Pete Seeger, a man who sees the genius in Dylan but also seems more than a bit stymied by his independent streak and his desire to move beyond the bounds of acceptable folk music conventions. I always enjoy getting to see a softer side to Norton’s acting persona, and one can feel Seeger’s increasing perplexity as the film goes on and Dylan’s star begins its meteoric ascent. For all of that, he remains fond of his protege even when their musical and artistic investments increasingly diverge, at least up to a point. In the end, even he has to admit defeat when his own wife keeps him from pulling the plug during Dylan’s electric guitar-infused performance at the Newport Folk Festival. The wispy old lion is defeated at last.

I was also quite struck by Boyd Holbrook's performance as Johnny Cash. Though he has only a few scenes in the film, there’s still a smoldering quality to his acting that makes him the perfect fit for Cash. Not to put too fine a point on it, but he really is sex on legs, and he has some potent chemistry with Chalamet (which is fitting, since Cash ends up being one of Dylan’s allies in his search for new musical outlets). Both Fanning and Barbaro are also excellent, and it’s refreshing that neither of them are ultimately willing to carry water for Dylan and his masculinist bullshit.

Ultimately, while I was definitely entertained by A Complete Unknown, I ended up being frustrated by its lack of true substance regarding Dylan’s artistry and his musicianship. It’s not till the last third of the film that we get a glimmer of insight into what makes him tick as a musician, but even the conflict between Dylan and the organizers of the Newport Folk Festival is more heat than light. At times in the third act it feels like Dylan is digging in his heels regarding the electric guitar and new sound business simply because he can and because, when it comes down to it, he’s become something of a diva as a result of his remarkable chart success. While I don’t think a monologue from Dylan explaining himself was necessary, it certainly couldn’t have hurt, either.

Where the film does succeed, though, is in situating Dylan in his historical milieu. At several points the film shows the tumult erupting throughout America during the 1960s, showing the extent to which this cultural and social ferment gave birth to artists like Dylan. Thus, despite my disappointment, I would rank A Complete Unknown as one of the better musical biopics that we’ve seen in recent years. Unlike, say, I Wanna Dance with Somebody or Maestro–both of which are more expansive in terms of the periods that they cover–this film zeroes in on a key moment in his life and career. It may not hit every note, but it’s still a symphony worth listening to.

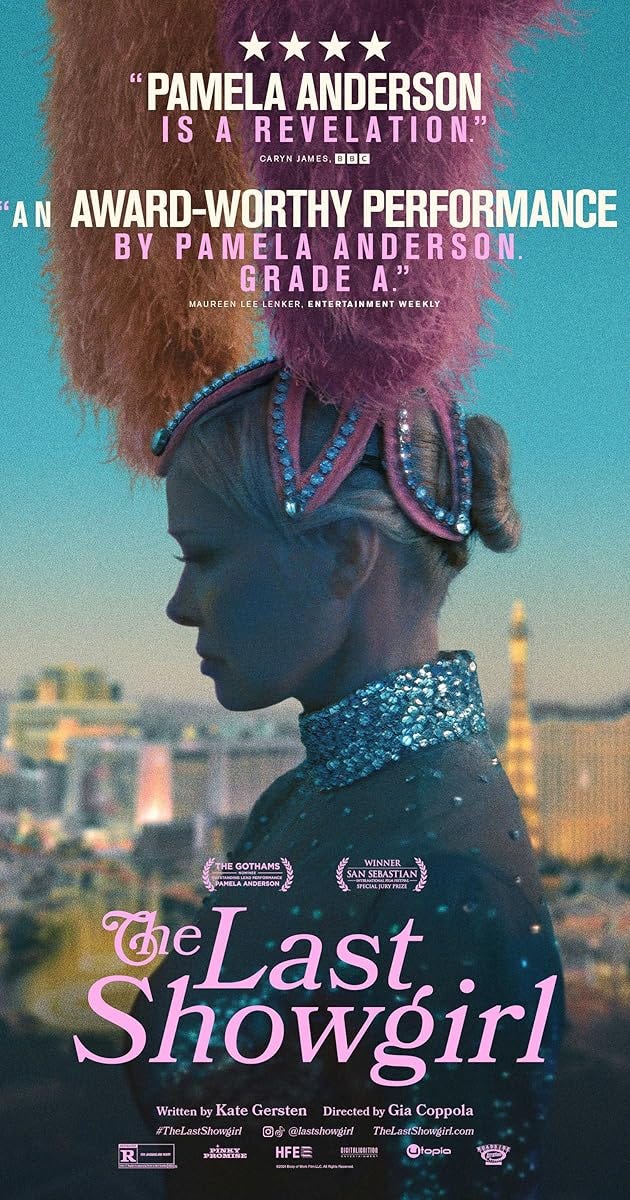

The price of show business is even more acute for Pamela Anderson’s aging showgirl Shelly Gardner, who finds herself at something of a loss when the Las Vegas revue of which she has been a part for the last 30 years abruptly announces that it is closing its doors. With no real prospects and no other experience, Shelly experiences a bit of an existential crisis. Aggravating matters are her vexed relationship with her daughter, Hannah (Billie Lourd), with the show’s producer, Eddie (Dave Bautista), and her fellow showgirls Mary-Anne (Brenda Song) and Jodie (Kiernan Shipka). The one bright spot in this is her friend, Annette (Jamie Lee Curtis), but even she has her own problems, and she’s notoriously brittle to boot.

As other reviewers have pointed out, The Last Showgirl is one of those films that shines a light onto the ways that women’s bodies are often used by an entertainment complex that cares little for them beyond the extent to which they can be used and then disposed of once they are no longer useful. Shelly is in many ways a relic of a past moment of glitz and glamor that can never be regained, one that provided women like her a measure of glamour and even a bit of upward mobility. There’s an poignant and piercing ache in those moments when she tries to explain to her younger colleagues–and, really, anyone who will listen–why this job has meant so much to her and why she will miss it when it’s gone. It’s not just the money (though that’s obviously a part of it); it’s that being part of Le Razzle Dazzle meant, for her, being part of something that was, in its own way, beautiful and fun and even artistic in its way. That world has now gone forever, replaced by cheap, sleazy acts focused more on immediate gratification than anything else. It’s Shelly’s tragedy that she’s caught up in this moment of one period’s demise and the birth of another.

I’ve always thought that we were all sleeping on Anderson as a true acting talent, and she demonstrates remarkable range and vulnerability in The Last Showgirl There’s a rawness to her that draws you in, transfixes you, keeps you riveted. It’s there in her mousy voice and her frail beauty–particularly evident in those moments when Shelly is shown without makeup, often dancing in her apartment–but it’s also there in the way that she tries to hold onto both her inner optimism and the sense of meaning that being part of the show provided her. The cracks are there, but somehow Shelly tries to find the joy in life even if, as happens at several key points, she can’t keep up the performance of happiness, even to herself.

What’s particularly striking about Shelly is how assertive she can be. This is no shrinking violet. Just because she has offered her body up for the visual delectation of adoring audiences doesn’t mean she isn’t quite conscious of her own rights, and she takes a great deal of pride in what she does. She makes this clear in a fraught conversation with Hannah, in which the latter comes to the show essentially to see whether what her mother does for a living was worth giving up a stronger relationship to her daughter. Shelly, however, doesn’t just roll over but, instead, fights back, claiming that she did the best that she could and that she’s through apologizing. Even if you don’t agree with her choices–and that’s certainly up for debate–you can’t help but admire her sheer force of will.

Then there’s the moment when she reads a casting director the riot act after he dismisses her (by essentially telling her that she’s too old). This is one of those feminist moments that I as a viewer absolutely love for in the movies. Up on that stage calling out the ageist and sexist assumptions of a man she can barely see, Shelly once again gets to reclaim her own agency, even if she doesn’t end up getting the part. One gets the sense that there’s more than a little bit of Anderson’s own career frustrations bubbling out into this extraordinary moment, as she shows just how much we’ve underestimated her all along, to our collective detriment.

The rest of the cast is universally excellent. Jamie Lee Curtis–who seems to have entered into the “serving cunt” stage of her career–plays Annette, a former showgirl herself who now works as a cocktail waitress and is, in her own way, even more tragic and aimless than Shelly. Dave Bautista gives an understated but remarkably touching performance as Eddie, and Lourd, as always, excels at playing a thoroughly disaffected young woman.

It really is a shame that Anderson’s remarkable performance in The Last Showgirl–and, for that matter, the film as a whole–has been shut out of the Oscars this year. There’s so much to love about this film, from its melancholy sweetness to its grappling with weighty issues ranging from aging to the fraught relationships between mothers and daughters (a late-in-the-film moment between Shelly and daughter Hannah definitely pulls at the heartstrings). Despite being shut out from the Oscars, we’re still fortunate to have this gem of a film, and it certainly augurs well for both director Gia Copola and star Pamela Anderson.