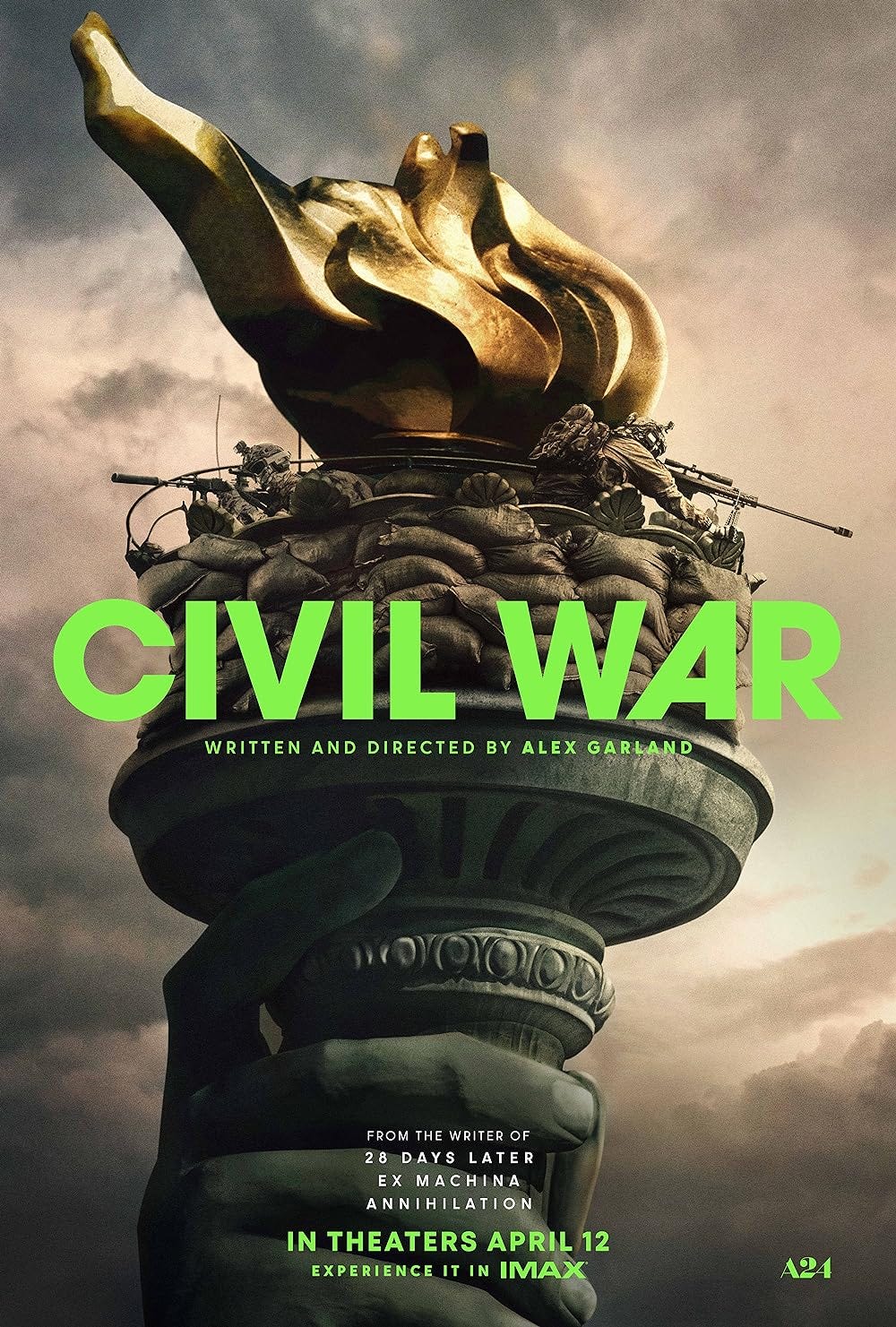

Film Review: "Civil War" is a Provocative and Deeply Frustrating Film

Alex Garland's weighty film excels at engendering strong emotions, but much of its supposed commentary rings hollow.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

I’ll be the first to admit that I had some reservations about Alex Garland’s Civil War. While I loved the director’s Annihilation–I still think it’s one of the best sci-fi films of the 2010s, if not of all time–I knew that watching this new film was going to be a stressful experience, if only because its very premise cuts so close to the bone. After all, we live in a time when a distressing number of Americans think that an armed civil war is either inevitable or very likely. However, I buckled up and decided to watch it, if only because it has proven remarkably successful at the box office and has generated a great deal of commentary.

The heart of the film is a quarter comprised of Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst), Joel (Wagner Moura), Sammy (Stephen McKinley Harrison), and Jessie (Cailee Spaeny). All but Jessie are seasoned journalists, and Lee and Joel are on their way to DC to snag an interview with the unnamed president (Nick Offerman) before he is deposed and presumably executed by the nebulous alliance known as the Western Forces, while Sammy wants to get some coverage from the front lines of the war in Charlottesville. As they embark on their little road trip, they pass through an American landscape torn apart and rendered barbaric by war (they even spend some time in my beloved home state of West Virginia).

Civil War is, I think, a breathtakingly audacious and troubling film, the kind of dystopia that emerges from troubled times. There’s no question that Garland is a master of his craft–capturing the grit and terror of the battlefield and getting some terrific performances from his cast–and I was rapt from the beginning to the end. At the same time, I also found myself frustrated with some of his choices, particularly concerning the stakes of the conflict that serves as the background of the film’s narrative. After all, if you’re going to call your film Civil War, it seems that the last you can do is explain to the viewer the contours of said war.

Now, I know I’m not the first one to complain about this; indeed, much of the critical conversation around Civil War has centered on Garland’s deliberate obfuscation about its causes, its belligerents, and even as basic a question as to who, exactly, is going to read the interview that Lee and Joel conduct (their snide comment to Sammy about the tattered remnants of The New York Times suggests that its readership is likewise diminished). It’s hard to see how the work that Lee and Joel undertake is so vital and important if we’re not even sure who is going to see the images and stories they capture, and not even the terrific performances from Dunst and company–and they are terrific, make no mistake about that–are even enough to make up for this glaring lack.

More concerning, I think, is the extent to which Black, Brown, and Asian bodies are, as Valerie Complex put it, “conduits for brutality.” Again and again we see how this civil war has exacted its terrible toll on the most vulnerable, and there are scenes that both literally and figuratively conjure up America’s sinister history of racist violence. One of the most disturbing scenes of the latter occurs when the group encounters a group of men protecting a gas station, who have strung up a pair of “looters” in the ruins of a carwash. I don’t think it takes someone with a degree in history to see this is as tapping into the gruesome lynchings that have been such a feature of the American past but, unfortunately, their demise lacks all meaning or significance beyond the fact that war is awful and it makes people do terrible things to each other.

Which brings us to the scene with Jesse Plemons, arguably the best scene in the entire film and the one that will linger the longest in the viewer's mind. After the foursome are joined by Tony and Bohai, another pair of journalists, they encounter a group of militants, led by Plemons who, after summarily shooting Bohai, interrogates the group, asking the terrifying question: “what kind of American are you?” He spares Lee, Joel, and Jessie but shoots Tony when he tearfully admits he’s from Hong Kong. As disturbing as the scene is, however, it also becomes just another tableau of horror in a film filled with them. It’s tense, certainly, and I was on the edge of my seat during the entire moment because of how plausible it all seemed, yet I was also struck by the banality of it. As terrifying as it is–and as nauseating as it is to see Plemons’ character and his fellow unloading a truck filled with Black and Brown bodies into a mass grave–it all seems like it’s just designed to be shocking and frightening. Not even Sammy’s rescue of the team and subsequent death by gunshot is enough to give it greater emotional or intellectual heft.

Thus, I found Civil War to be a provocative yet cynical film, the type of dystopian fiction that allows all of us to vicariously experience what could be argued is one of the worst of possible futures without ever explaining how it came to this. And, while it seems to have been Garland’s intention to speak to the inherent nobility of photojournalism, I found myself agreeing with those who thought it ended up doing the opposite. In the end Lee has become just another body strewn in the wake of the war, her demise captured by Sam in the midst of its happening, while Joel, an adrenaline-chaser to the last, gets a final pathetic statement from the president before standing back and letting him be extrajudicially killed by soldiers with the Western Forces, before Jessie captures an image of the soldiers standing around their kill, like so many poachers around the slaughter. It all leads one to ask: what was it all for?

But then, perhaps that’s the point. We live in a profoundly cynical age, one in which all of us have become increasingly inured to spectacles of violence, inundated as we are by such scenes each and every day. It’s for this reason that I am particularly haunted by the last image of the film, that grim and gleeful photo of soldiers celebrating around the body of a dead president. Yet even here there is still that frustrating lack of emotional context and weight. Yes, as people have been at pains to point out, we know this particular president has served an unconstitutional third term and disbanded the FBI and launched airstrikes against American citizens. But we know nothing else about him, nor about the country in which all of this is taking place. Like so much else in the film, it’s a moment of horror and death and brutality, an empty perspective signifying nothing.

Not every film that asks tough questions has to provide answers, of course, but it does seem to me that the film promises more than it delivers. It is a film filled with big ideas and big feelings and sensations, and while many of these will linger in my mind for some time to come, the film itself will not. It might skillfully call upon all sorts of present-day anxieties and concerns–among them the grisly photos from Abu Ghraib–but it ultimately does very little with them. Ultimately Civil War is a film with a lot to say but, sadly, not quite sure how to say it.