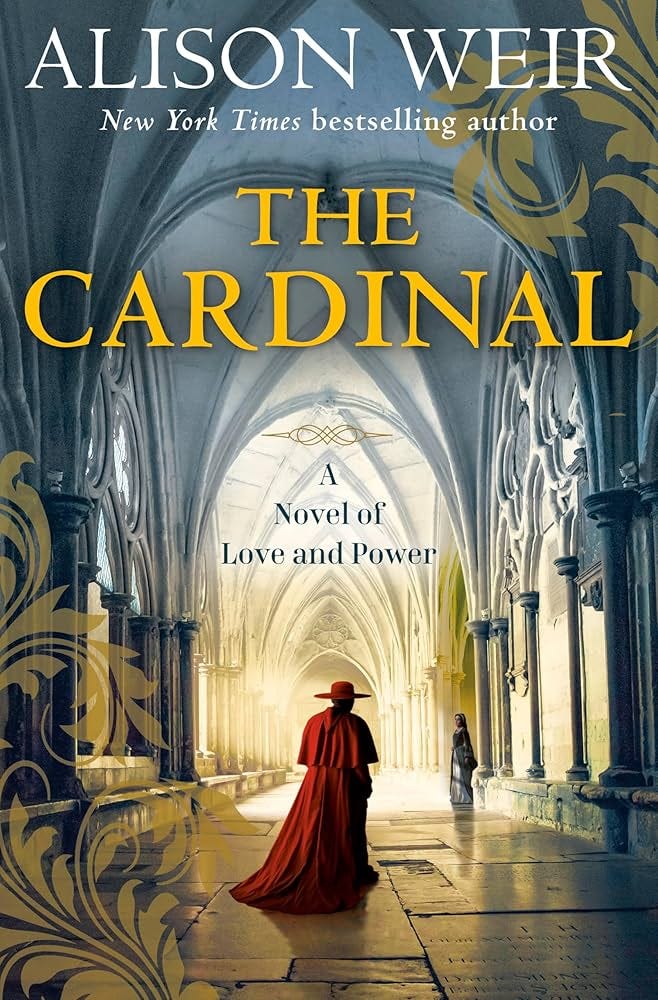

Book Review: "The Cardinal: A Novel of Love and Power"

Renowned historical novelist Alison Weir's newest book is an overdue fictional biography of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Henry VIII's most loyal and powerful minister.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free!

As an added bonus, every month I’ll be running a promotion where everyone who signs up for a paid subscription will be entered into a contest to win TWO of the books I review during a given month. For April, this will include all books reviewed during March and April. Be sure to spread the word!

Warning: Spoilers for the novel follow.

If Henry VIII could be said to have had one courtier who loved him more than all others, it would have to be Cardinal Wolsey. Portrayed by such memorable actors as David Suchet (in the ITV drama Henry VIII), Sam Neill (in The Tudors), and Jonathan Pryce (in Wolf Hall), he was a true statesman and a remarkable example of someone who in no way let his humble origins stand in the way of his desire for power. Now, he at last gets a historical novel that tells of his life from childhood to death, and Alison Weir’s The Cardinal is a fitting testament to one of the most extraordinary figures of the Renaissance.

Weir makes no bones about the fact that Wolsey was a remarkably ambitious man, someone who yearned for the finer things and life and wasn’t shy about reaching out for them when the opportunity presented itself. One can hardly blame the man. Who among us wouldn’t have done as he did, if we were unfortunate enough to be born among the lower classes of Tudor England? Once it becomes clear that he has a sharp mind and is suited for a life in the church, he goes from success to success, rising through the ranks and becoming cozy with first Henry VII and then his son, Henry VIII (who we will refer to as Harry, as this is how the novel talks about him). Time and again we see that Tom Wolsey is the type of man who has his eye on the main chance, and we can’t help but cheer for him.

At the same time, he’s so much more than just a scheming social climber. Weir makes it clear time and again that Wolsey really does care about and loves Harry, for all that the latter is a monarch who is far more interested in himself than in anyone else, including the man who has made so many of his creature comforts possible in the first place. The higher Tom rises, the more aware he becomes that Harry is like the sun; when you fly too close to him, you run the risk of being burned, perhaps beyond repair. This, though, was the nature of life in the Tudor court, in which all blessings essentially flowed from the king.

And, of course, it’s all made that much worse by the fact that Wolsey is surrounded by people who resent him for his low-born origins, particularly Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk and Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. As would be true of Thomas Cromwell somewhat later, the members of the nobility could never bring themselves to forgive someone who had managed to break free of the tight bonds of the Tudor social hierarchy. The fact that he plays a key role in keeping Brandon from being accused of treason after he marries Harry’s sister Mary just gives him that much more reason to hate the Cardinal.

There’s no question that the most important emotional relationship in Wolsey’s life is that which he shares with his mistress, Joan. Even though he knows that pursuing a relationship with her entails breaking his vows, such is the powerful bond between them that he’s willing to put his soul at risk in order to be with her. One of the great heartbreaks of his life comes when Harry, never someone to give his nobility and clergy the benefit of the doubt when it came to issues of sexual morality–despite his many well-known and very public affairs with women not his wife–essentially forces him to give her up. For the rest of his life he will continue to pine after her and attempt to find a way to be with her, even though doing so ends up causing her more pain than pleasure. His relationship with Joan really helps to humanize him, and Weir wisely shows us how Wolsey, like so many of his, contains multitudes.

Ultimately, of course, Wolsey falls victim to Harry’s capriciousness and willingness to turn on those who don’t give him what he wants when he wants it. Once Harry sets his sights on dissolving his marriage to Katherine so that he can marry Anne Boleyn, Wolsey’s fate is also sealed, since he finds that it is not as easy to enact the king’s will as he might like. Adding to his difficulty is the fact that Anne refuses to let go of her enmity of him, which he earned when he undercut her efforts to marry Henry Percy. The fact that Harry gave his approval to Wolsey’s actions in the Percy affair matters little and, along with her father and uncle, the powerful and resentful Duke of Norfolk, she becomes one of Wolsey’s most implacable enemies.

The last part of the novel chronicles Wolsey’s calamitous fall from grace as Harry turns fully against his former favorite. Tom’s fate is a brilliant illustration of the vicissitudes of fate and fortune, for as much as fortune’s wheel could bring a person to such power and prestige, it could also bring them to ruin. Thanks to Weir, however, we are invited to see this is a very human tragedy rather than as an example of just desserts. It’s impossible not to feel sorry for Wolsey as his world falls apart around him and all of the power and privileges he’s accrued are slowly stripped away from him as his enemies gain more influence over Harry and the king, ever willing to punish those who fail him, talks out of both sides of his mouth.

Many of Weir’s biographical novels take us right up to the moment of their protagonist’s death, and The Cardinal is no exception. As the novel closes, Tom shuffles off of this mortal coil, and it’s really rather wrenching, depressing even, to know that all of his accomplishments have essentially been for naught. He’s left behind a reprobate son and a daughter who is sent to the cloister–as well as Joan and perhaps a few other children–but since he wasn’t able to acknowledge them, they aren’t truly part of his legacy. Even his college at Oxford would end up being taken over by Harry. It’s a rather dismal fate for someone who gave so much of himself for an ungrateful and selfish sovereign.

The Cardinal makes for an immersive read and, as she has shown time and again, Weir is truly an expert on the daily life of the Tudor era. She brings her formidable knowledge of the period, its costumes, and its people to bear as she shows us what daily life was like for those of the time. As she does in her biographies, she makes sure that we know more than we ever thought we needed to know about the material culture of the time which, while sometimes dryly delivered, nevertheless gives the reader an appreciation for just how much wealth Wolsey was able to accrue. Her prose is workmanlike rather than inspired. This is obviously not a criticism, but if you’re looking for something with the lyricism and evocativeness of Hilary Mantel or the luscious indulgence of Philippa Gregory, then you’re likely to be disappointed.

All in all, I would say that The Cardinal is a lovely addition to Weir’s voluminous output. She has repeatedly shown that she has the ability to be as compelling a fiction writer as she is as a popular historian. It’s also just fun to spend time with Wolsey, who I’ve always found to be as fascinating as Henry VIII himself. At last, he finally gets his due.

My thanks to NetGalley for an advance review copy of this book.