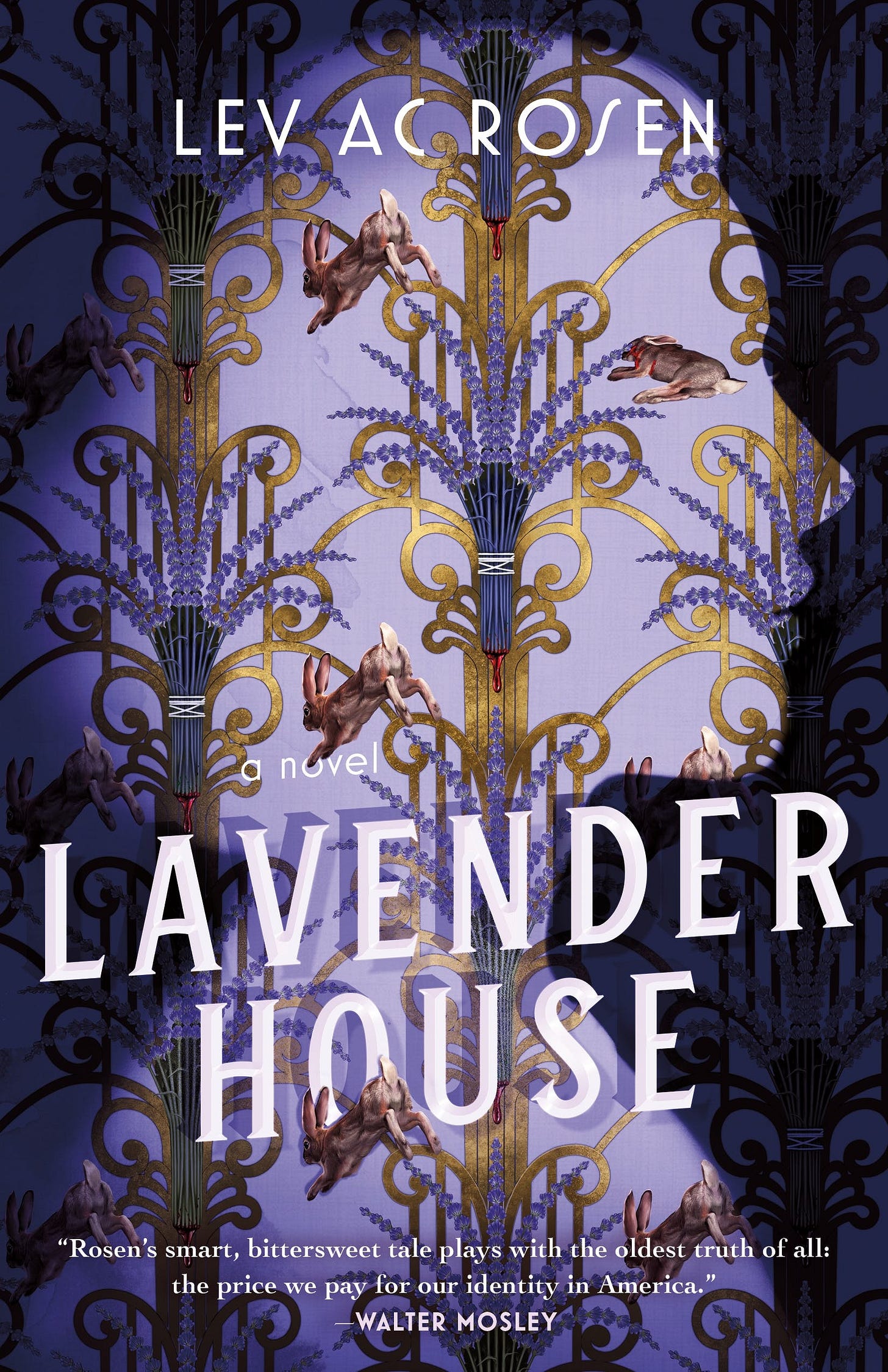

Book Review: "Lavender House"

Lev A.C. Rosen's novel is a delightfully queer spin on classic hardboiled fiction.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

If you know anything about me, it’s that I love a good film noir and I love a good queer story. Fortunately for me, these two loves come together in Lev A.C. Rosen’s novel Lavender House, which follows disgraced policeman Andy Mills as he tries to solve the mystery of who murdered the wealthy owner of a soap company. In the process he becomes a key part of a little queer enclave that the deceased has created in her vast mansion. Part film noir and part queer historical fiction, this was a very satisfying read that left me hungry for more from this fictional detective.

When the story opens Andy is struggling with suicidal thoughts. The setting is early 1950s San Francisco and, though a member of the police department, he was caught in a gay bar during a vice raid, leading to his expulsion from the force. Fortunately for him, he’s spotted by Pearl, whose wife has recently died under somewhat mysterious circumstances. She offers him a lucrative position as a private investigator, and it’s not long before he is ensconced in her beautiful home, where almost everyone is queer and where anyone could be the killer.

In fact, it becomes clear right away that Irene and Pearl managed to create a queer little oasis, one in which everyone is entitled to live their authentic selves. This includes their son, Henry, who has a boyfriend and a wife (though the latter is queer). Even the servants are members of the family, and none of them are particularly happy that Pearl has hired Andy to poke around their private lives. To many of them, it would be much easier if he just accepted the idea that Irene died of natural causes. However, Andy isn’t going to be put off lightly, and Rosen paints a deft portrait of both the various inhabitants of the house and Mills’ investigative methods.

One of the best things about Lavender House, however, is the skill with which Rosen immerses us in the world of Cold War America. Andy, like so many other queer people of his generation, has gotten by so far by living in the shadows, using his insider position as a member of the police force to ensure that he is never snared in a raid; it’s only a mishap that leads to his apprehension. Indeed, one of his moral dilemmas throughout the novel revolves around the guilt he feels about not doing more to warn the fellow bar patrons of the impending raids. His experiences at Lavender House bring home to him just how important a community really is, and it reminds us, in the present, that there was a thriving queer consciousness even before the events of Stonewall.

The central mystery at the heart of the novel is, in hindsight, quite obvious, but as with so many noirs the pleasures of the novel come from its atmosphere and its characters. Andy is far from your typical hard-boiled hero for, while he does have some rough edges, he is remarkably introspective and willing to admit his own flaws and foibles. What’s more, there is a sensitive side to him, too, and Rosen allows us to see the many things that he has had to give up as a result of being a gay man living in a homophobic world. Among other things, he has distanced himself from his family, fearing (probably rightly) that they would look at him with scorn and disgust. There is something very noir, however, about the idea of a harsh and unforgiving world, one in which the lonely man is cast adrift to fend for himself.

Lavender House is, thankfully, not nearly as cynical as one might expect from a novel that partakes of the noir tradition. There is darkness, to be sure, and the book doesn’t shy away from showing us just how virulently homophobic Cold War America was and, more to the point, how dangerous. Each of the characters has to grapple with the fact that, should they show themselves who they are outside the walls of the house, they run the risk of being exposed. It’s only Pearl’s considerable wealth that keeps the truth about them from being exposed to the general populace. Queer happiness is possible in the world that Lavender House creates, but it is a precarious sort of happiness, one that is only maintained with great effort and with the imposition of a code of secrecy.

Ultimately Andy’s discovery of this little island of queerness gives him a reason to live. When the novel begins, he is so immersed in his own depression that he can see no alternative but to throw himself into the Bay; by the end, he’s realized that there is a lot to live for, that he can do a great service to his fellow queer folks by being a private detective. I have to admit that I absolutely loved this ending. Not only does it allow Andy to put his skills as a policeman to work; it also allows him to make amends for all of the times that he did nothing to protect his fellow queers. He’s now a part of that community, and that comes with its own set of obligations.

A few stray observations. The cover is absolutely gorgeous, capturing just the right tone. I’ve also heard it said that this book is like a queerer version of Knives Out. While I think that there’s some truth to that, I think it would be more accurate to draw comparisons to the classic films noirs of the past, such as Double Indemnity and The Big Sleep (though thankfully it’s more comprehensive than the latter). I also had the privilege of seeing Rosen speak at the History Book Festival in Lewes Delaware a couple of weeks ago, and he is as delightful as one could hope for.

The next volume in Andy’s adventures is already in bookstores now, and I can’t wait to get my hands on it!

Really loved this one, too! Thanks for reviewing -- I was so excited to see this pop up here. The world-building was so cool, and I also agree that the mystery was fairly obvious in retrospect (as well it should be, considering the framing of the queer plot), but I feel that Rosen did such a good job of planting those little mysterious red herrings around the story.