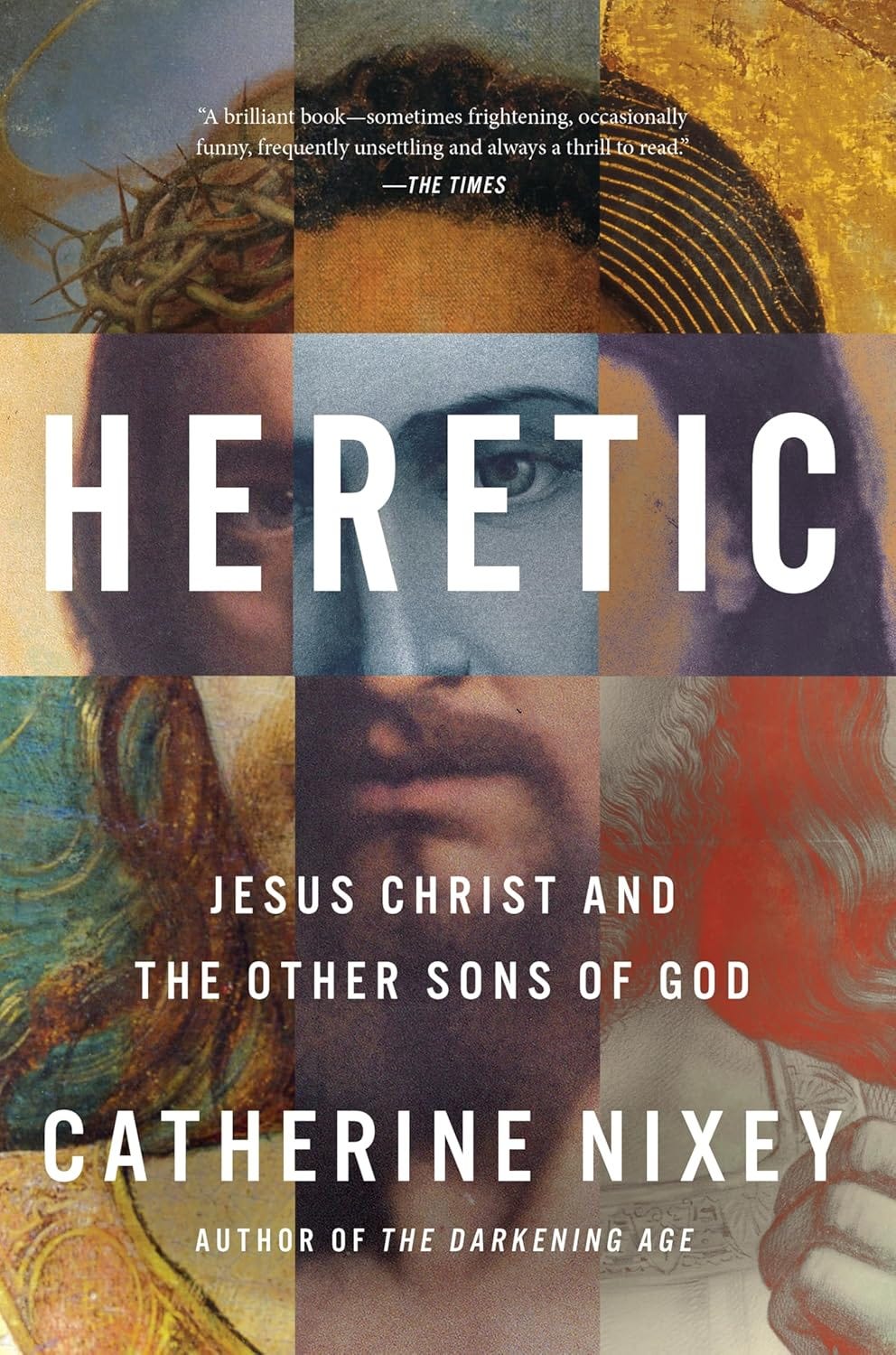

Book Review--"Heretic: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God"

In the follow-up to her book "The Darkening Age," Catherine Nixey offers a flawed but engaging examination of the fertile period of early Christianity.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Just a reminder that I’m running a special promotion here at Omnivorous for the whole month of May. If you join as a paid subscriber, you’ll be entered into a raffle to win a gift card to The Buzzed Word, a great indie bookshop in Ocean City, MD. Check out this post for the full details!

I remember being impressed–if at times frustrated–by Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age, her scathing screed against early Christianity and its determination to destroy the pagan past. It was clear from that book that Nixey was someone who was very skilled at writing a certain polemically-inflected sort of popular history and, if she took some notable liberties with the historical evidence (cherry picking is a term that’s usually used to describe her work in that book), she did at least draw some much-needed popular attention to Christianity’s tendency to dispense with those elements of the pagan past that they didn’t find useful.

Now, Nixey has returned to the same period with Heretic: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God. Here, her focus is on the various other sects and figures that emerged in the first few centuries of the Common Era, as those who found themselves captivated by the nascent Christian faith and its various writings did battle with one another in an attempt to win converts and establish whose version of the faith would ultimately earn the honor of being declared orthodoxy. It’s a lively and fast read that, like its predecessor, draws important public attention to a key moment in the history of Christianity even if, also like The Darkening Age, it tends to be rather slight and reductive in its analysis.

Nixey’s helpfully situates early Christianity in all of its strangeness against the larger Greco-Roman world and, as she demonstrates, many of the thinkers of antiquity were quite perplexed about the nature of Christian doctrine and belief. Not only that; they were determined to demolish what intellectual credentials the Christians had attempted to build for themselves. The Greek philosopher Celsus, for example, frequently waxed eloquent on what he saw as the grievous shortcomings of this new faith springing up in the Roman Empire, as did the emperor Julian, the last pagan emperor to rule. It must be said, however, that Nixey is curiously reticent about paying attention to what Christians had to say about such attacks.

Nixey really hits her stride when it comes to discussing the various texts that, for one reason or another, didn’t make it into the Bible itself. Those of us raised in a Protestant tradition are, as Nixey assumes, probably largely unaware of some of the more bizarre iterations of Jesus that appear in such texts as The Infancy Gospel of Thomas. This Jesus is far from the figure that we meet in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and is, it has to be said, quite an unholy terror. Many of these books were, unfortunately, lost to subsequent generations, meaning that contemporary scholars often have to rely on their enemies for an indication of what they actually contained. As Nixey observes, they are both signifiers of roads not taken as well as illustrations of just how complex Christianity was in its early days (and remains, despite the eventual triumph of orthodox belief).

Moreover, Jesus wasn’t the only wandering philosopher performing miracles during the first couple centuries of the Common Era. One of his likely contemporaries was Apollonius of Tyana, who raised people from the dead and performed various miracles. And, like Jesus, he was ultimately put on trial, though rather than being executed he simply vanished. Though there are obviously some key differences between these two figures, the parallels between them are quite surprising, particularly if you have never heard of Apollonius of Tyana. By bringing such figures into the light, Nixey usefully demonstrates the extent to which Jesus, and the religion that sprang up around him, was very much a key part of its world rather than, as some Christian exceptionalists would argue, something entirely new. Indeed, it is perhaps because Christianity so adeptly tapped into the desires and yearnings of the first decades and centuries of our era that it became as successful as it did. There was clearly something in the air in the Mediterranean during this period of history that called for a faith promising some form of escape from the trials of the present reality.

Overall, I found Heretic to be a fun and lively read, if at times a bit frustrating. Nixey tends to mistake her premise for her conclusion, by which I mean she tends to go into an analysis of early Christianity expecting to find evidence of the powers-that-be destroying those texts so that the way can be cleared for orthodoxy. While it is certainly the case that many early Christian thinkers made an effort to distinguish the rightness of their point of view from that of those with whom they were contending, and while there were certainly official efforts to suppress such mistaken belief, there were always complications. Contrary to what Nixey–and popular historians writing in her style seem to think–history is rarely as clear-cut as we might like. Though Heretic isn’t nearly as didactic as The Darkening Age, it does sometimes become as preachy, and as determined to enforce its view of how things happened, as the very pedantic early Christians that it criticizes.

In terms of style…may just be me, but I’m not a huge fan of the tendency among many popular historians to lard their prose with bons mots and witticisms. These have their place, obviously, and I don't mean to be prissy about such things, but in books like Heretic they can become quite distracting and end up undercutting the seriousness of the argument that Nixey is trying to make. In that regard I was reminded more than a little of Tom Holland’s style, which similarly leans too much on cleverness instead of sound argumentation and scholarly rigor. Humor and clever remarks have their place, but they can quickly become cloying and distracting.

More concerningly, she claims early on in the book that it remains unusual for academics from different disciplines to engage with the New Testament and Early Christianity as matters of history rather than simply faith. Nixey frames this as a sort of gentlemen’s agreement between theology and classics, and I’m just not convinced that this is the case. In fact, I’m fairly certain that it is not and that it hasn’t been for quite some time. Indeed, there has long been a fruitful collaboration between these two fields of study, particularly in the last fifty years. To claim otherwise is to be deliberately misleading, and I can’t help but suspect that this was an effort on Nixey’s part, or perhaps her publisher’s, to make the case that this book is doing something new when, in fact, it is largely hoeing the same row that has been explored by such equally popular historians of religion as Elaine Pagels and Bart Ehrman (both of whom, for my money, are more rigorous than Nixey and just as accessible).

For all of that, Nixey deserves credit for drawing our attention to the fertile period of early Christianity, one in which it was far from clear what version of the faith would emerge as the dominant one. While her arguments are at times clumsy and while, as some have pointed out, the book can sometimes feel a bit slight, I think in the aggregate it’s a good thing if more people grapple with the complexities attendant on understanding early Christian history. Nixey might be a bit of a flawed vessel for bringing these issues to light but, at the very least, she is also a very entertaining one.