Book Review: "Blood over Bright Haven"

M.L. Wang's dark academia fantasy novel is a haunting and resonant tale about the price we pay for civilization and progress.

Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Warning: Full spoilers for the novel follow.

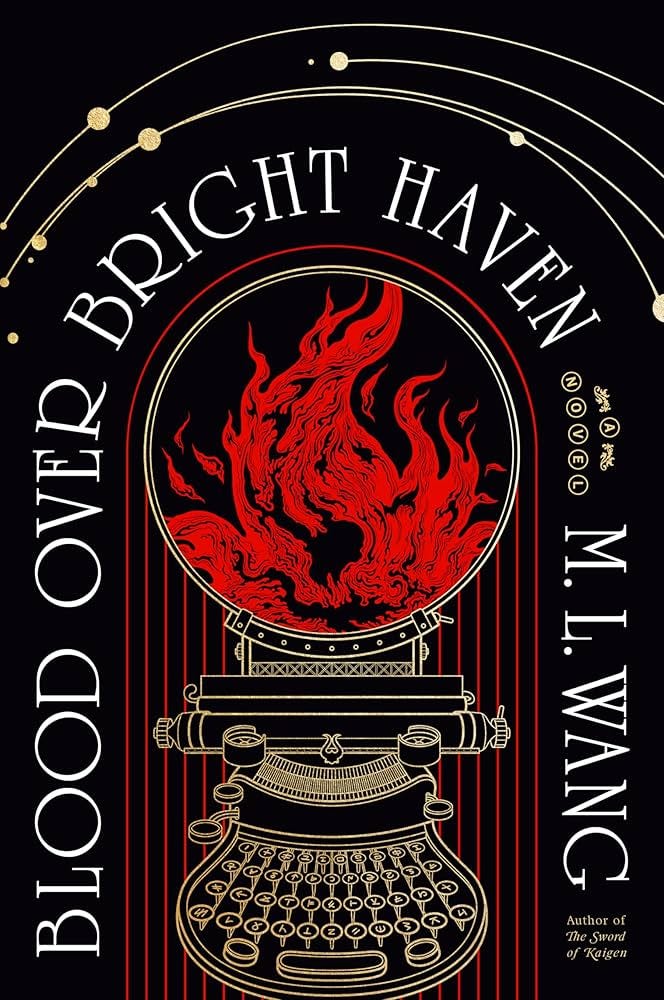

As so often seems to be the case these days, I discovered M.L. Wang’’s Blood over Bright Haven by accident, stumbling upon it in the new releases section at the library. It had just the kind of cover that’s designed to draw you in–all reds and blacks–and the plot is a mix of dark academia and thriller. Wang effortlessly blends these elements together into a heady cocktail that is a bitter but bracing draught.

The novel is largely set in the industrial utopia of Tiran, a city whose primacy and success relies on magic. The main protagonist is Sciona, whose aspirations to join the High Magistry are finally realized as the novel begins, and she manages to impress those responsible for admitting new members. While she is a woman, her skills at magic are undeniable and, with the aid of her assistant Thomil–a member of a subaltern group known as the Kwen–she manages to discover secrets about her people and their use of magic that are as devastating to her as they are to Tiran as a whole.

I suppose I should have seen the twist–that the source of this society’s industrial magic are all of the people and things living outside of the bounds of the city and, as a result, the horrifying phenomenon known as Blight, which tears living things apart–but even so, it hit me like a ton of bricks. One can see why such a revelation would be shattering for someone like Sciona, who has devoted her entire life to pursuing magic in the belief that it was an intrinsic good. Her mental breakdown is the kind of response that anyone would have when faced with the reality that their entire society, with all of its beauty and its accomplishments, is essentially based on mass murder.

Obviously the metaphor–or allegory, depending on your point of view–isn’t subtle, but it is nevertheless effective. The mark of an effective magic system in fantasy is its ability to adhere to its own internal rules and structures, and this is precisely what makes Wang’s imagined scenario so frightening. It’s precisely because the processes and source of magic have been so abstracted–through the use of such mechanisms as spellographs and spellpaper–that supposedly good men can engage in their horrors. Well, that and they’re egotistical and delusional and want nothing more than their own advancement, no matter the cost.

One of the most haunting moments in the book occurs when Sciona, devastated by what she’s learned about her homeland and the pursuit of magic to which she has devoted her entire life, takes her discoveries to her mentor, in the hopes that in doing so she can right the wrongs. Rather than responding with outrage, however, he makes it clear that he’s known all along and, infuriatingly, he tells her that it isn’t seemly or in good taste to discuss the truth about magic openly.

It isn’t seemly. That’s the justification he gives for why he and the other mages don’t want to talk openly about the fact that they have to commit mass murder in order for their magic system to work. It’s a sentiment that is truly terrifying in its banality and yet, one can also see why for a man like this that would be the most important thing. When it comes down to it, for all that he has supported Sciona and been one of the few men who is willing to give her the chance to pursue the magic that is her lifeblood, the most important thing is that he helps to maintain the fiction that they are all good people. The key to that, of course, is civility and, of course, the persistent fiction that the Kwen are subhuman and their sacrifices are just the price of progress.

Indeed, it’s really quite remarkable the extent to which the people of Tiran have built contempt for the Kwen into every bit of their society, from their religion to their social mores, their legal system to their daily lives. The Kwen are, for far too many people, a truly subaltern group in every sense of the term, and so great is this belief that not even the revelation of the truth about magic is enough to convince the Tiranish to save their minds. If anything, they’re even more determined to crush those under them, particularly when the Kwen engage in widespread rebellion. After all, nothing unites the privileged and the powerful like having those in a lower caste to hate.

Blood Over Bright Haven is one of those books that really forces the reader to contend with some troubling questions: about the nature of society, of progress, of civilization itself. It also grapples with thorny questions about morality, and the extent to which one’s intentions should be weighed in the scales. Sciona and Thomil are each fully-drawn characters in their own right–with their own investments and personalities, their flaws and strengths–and as they contend with both their own conflicts and with the broader ethics of the world around them, you actually find yourself loving both of them in equal measure. The ending manages to be both tragic and satisfying, while leaving open the possibility for future installments.

What’s so terrifying about Blood over Bright Haven is just how plausible it all is. What is electricity and all of the trappings of modernity that it enables and undergirds, but its own form of magic? And one doesn’t need to look too far to see the extent to which the people of Tiran are very much like so many of us: willing to turn a blind eye to the injustices of the world around them–from misogyny to racism–simply in the interest of maintaining their own privilege and not rocking the boat. Injustice of all kinds are interlocking and mutually supporting, and this novel beautifully and powerfully explores those dynamics. In a world in which Trump and Trumpism seem ever more dominant and in which far far too many people seem more than happy to harm others so long as their own privileges are secured and kept intact, and even when they’re not, stories like this one are all the more necessary.

All of this is a long way of saying that Blood over Bright Haven is a remarkable and haunting piece of fantasy. It’s everything I love about the genre and then some. It’s one of those pieces of fiction that truly sits with you long after you’ve finished it. And, because it doesn’t end exactly happily, it reminds you that there is still much work to do, that the defeat of evil is an ongoing process that is never fully finished.

It’s a message that grows more potent with every passing day.