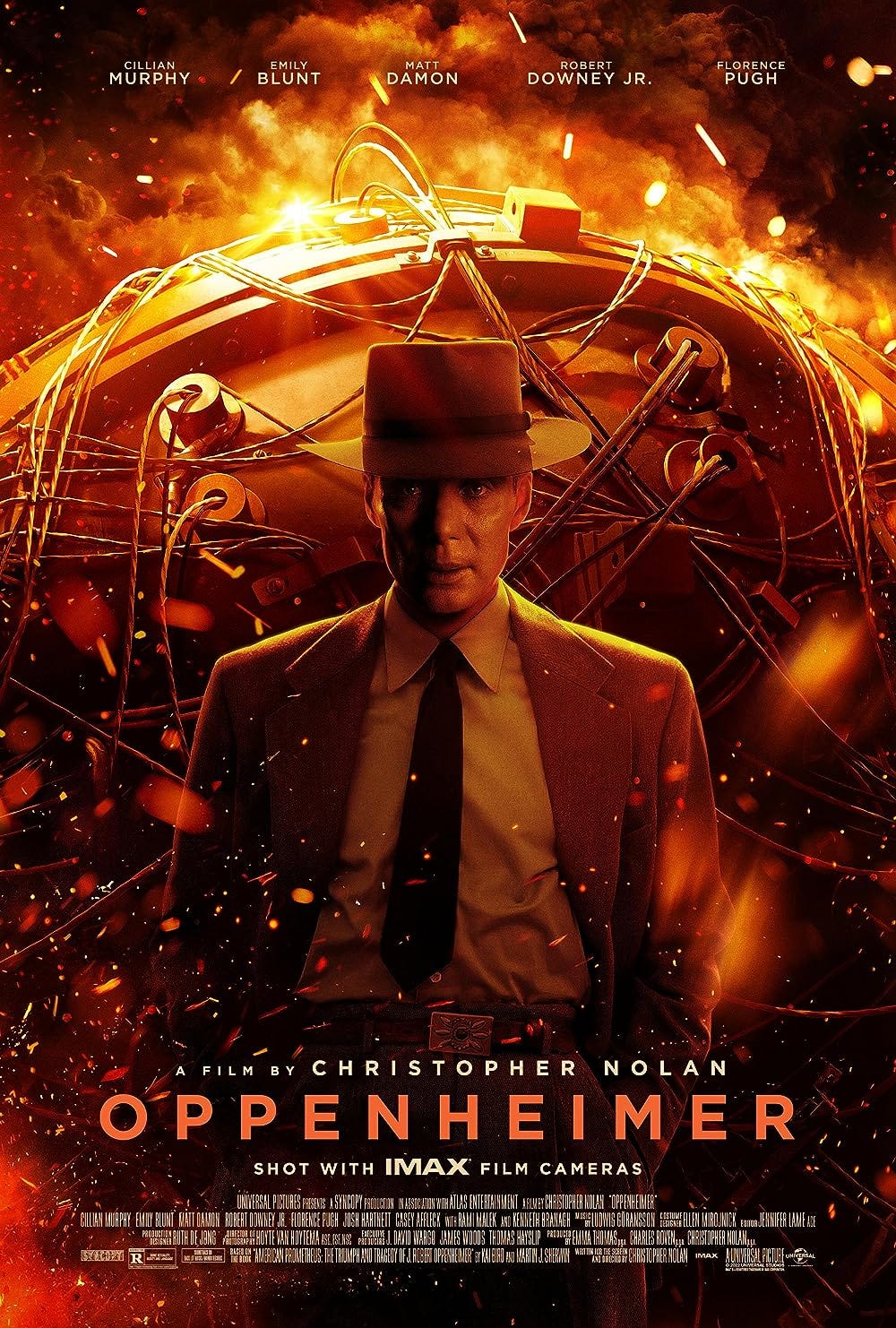

Agency and Impotence in Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer"

Like the best atomic fictions, Nolan's film reminds us of the dual nature of the bomb and humanity's use of it.

As someone who has long been interested in the atomic bomb and its enduring impact on the culture of the post-war world, I went into Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer with sky-high expectations. I knew the broad contours of Oppenheimer’s life and the situation that gave rise to the detonation of the first atomic bomb, but I was looking forward to seeing Nolan’s take on the story. Suffice it to say that I was not disappointed, and the film is epic in every sense of the world, giving us insight not only into the man’s psyche but also the world of which he was a part.

One of the most striking things about the film is the extent to which it sets up a narrative tension between impotence and agency, particularly as these manifest in Oppenheimer’s drive to create the bomb and his subsequent realization that this is a genie that most definitely can’t be put back in the bottle. Like the mythological Prometheus–whose myth is revealed to us at the beginning of the film–Oppenheimer has to bear the cost of bringing such a tremendous power into human hands, though his punishment, unlike his Titanic forebear, is of a decidedly mortal rather than divine sort.

From the beginning of the film, it’s clear that Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer is cut from a different cloth, and the Irish actor imbues Oppenheimer with a nervous, almost frantic, energy, as he is constantly stymied by the limited imaginations of those who can’t see the possibilities in quantum physics. As he repeatedly proves his acumen, he is ultimately drawn into the federal government’s desire to build an atomic bomb. Ultimately they are successful and, in many ways, Trinity marks the apex of Oppenheimer’s power. Despite all of the doubts, he is now at the apex of his influence. At the same time, the sheer spectacle of the explosion itself–the towering and terrifying pillar of flame, the delayed burst of deafening sound, the simple fact that it has worked at all–all combine to somewhat puncture his claim to victory. How could anyone, even a man of his towering intellect, ever hope to control such a force?

Very soon, however, it becomes clear that Oppenheimer’s lack of control extends to the larger bureaucracy surrounding his project. Though he is consulted as to which targets the military should strike–including those which are eventually chosen, Hiroshima and Nagasaki–it’s very clear that no one in the chain of command takes him very seriously. Likewise, his anxious warnings about the perils of developing a hydrogen bomb are summarily waved aside by those in power. In terms of the narrative, Oppenheimer has lost control of the very thing that he brought into being.

It is his conflict with Robert Downey Jr.’s Lewis Strauss, however, which reveals Oppenheimer’s lack of agency. The postwar world is very different from the one in which he came of age and came into his power, and Strauss has a keener understanding of the workings of power. To that end, he manages to ensnare Oppenheimer in a sham proceeding in order to have his security clearance and thus torpedo his influence on public policy. The fact that Strauss’s efforts are largely the result of personal jealousy and bitterness over a public humiliation he suffered at Oppenheimer's hands reveals just how fickle the tide of history can be, even for someone who was so pivotal in bringing the bomb into being. Even his vindication isn’t of his own doing–he knows virtually nothing about how the levers of power work–but instead that of a group of concerned scientists. The various scenes associated with his trial–which largely takes place in a dimly-lit room far from the public eye–accentuates Oppenheimer’s impotence in the face of bureaucratic power and Washington politicking.

This dichotomy extends even to Oppenheimer’s relationships with women. Though he is a married man, he also engages in a sensual affair with Florence Pugh’s Jean Tatlock, the little death of his orgasms with her clearly connected to his own transformation into the bringer of mass death. He seems at first to have the upper hand in their dynamic–he’s the object of her desire–but her she ultimately takes her fate into her own hands, taking her own life and leaving him to ponder his own role in her death (and that of the millions who might perish at any time due to a nuclear bomb).

As with so many other films influenced by the advent of atomic technology, Oppenheimer shows us the extent to which the bomb was always a double-edged sword. Indeed, it provoked nothing less than an entire epistemological change, as humans finally had to reckon with the fact that they now had it within their power to destroy themselves, something that had previously been in the domain of the natural or the divine. With such a revelation, however, also came the recognition that there was very little that an individual person could do to prevent such a thing from happening. As we see throughout this film, this extends even to the man who, upon seeing the weapon in all of its terrible glory, remarked (drawing on the Bhagavad Gita), “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

We see this most clearly in the film’s final scene, which is a flashback to an earlier moment when Oppenheimer met an aging Albert Einstein. It’s the moment that neatly crystallizes the entire film’s view about the power and peril of atomic technology, as Oppenheimer admits his growing conviction that he has brought a power into the world that will ultimately lead to humanity’s demise. It’s a haunting confession from this brilliant man, this individual who has a good claim to be one of those few people whose actions and intelligence truly did shift the trajectory of history. When the film closes on his tormented visage, it both evokes the fate of the tragic Prometheus–chained to a rock, his intestines devoured by an eagle for eternity–and reminds us of the inevitability of death for all of us. Like the best atomic fictions, Oppenheimer reminds us of the contradictory nature of modern humanity, at once in control of its fate and yet powerless to prevent its own essential finitude.

It’s a perilous reminder, and one that we would all do well to heed.